Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.

Thanks for the reply and the info. I hope the lawsuits can change thing or at least postpone them. I agree $4.50 seems really low to me.

Scott...I bought RESN because I always thought it was a potential buyout candidate. However, I did think it was worth more than $4.50 a share and still do. Trying to read through the mumbo jumbo legal wording in the SEC filings it looks like 4 other companies explored buying RESN, 2 of which it seems do not want to outbid Murata because of their own development products and 2 others don't think they can submit a bid within the timeline that Murata has established to finalize the buyout. So unless those 2 other companies can fast track a competitive bid offer I guess we are stuck with $4.50. I do see there were a number of lawsuits listed in today's (3/14/22) SEC amended filings related to the buyout.

So the offer is out and as far as I can tell share holders have no choice in the matter. You will get 4.5 a share if you decide to sell them or not. The only difference is when you will be paid. That sucks. I purchased my shares because I figured the company probably had a bright future. I can't believe no one is saying anything about this.

Can anyone explain to a slow old man what will happen to my shares now that resonant is being bought out?

Wow I guess I got caught with my head in my ass. Or you can say I wasn't paying proper attention. This really caught me by surprise. Can anyone explain to a slow old man what will happen to my shares no that resonant is being bought out? I thank you for any help you can provide.

Per announcement and 8K filing Murata will buy RESN for $4.50 per share.

Item 1.01 Entry into a Material Definitive Agreement.

On February 14, 2022, Resonant Inc., a Delaware corporation (“Resonant” or the “Company”), entered into an Agreement and Plan of Merger (the “Merger Agreement”) by and among the Company, Murata Electronics North America, Inc., a Texas corporation (“Murata”), and PJ Cosmos Acquisition Company, Inc., a Delaware corporation and wholly owned subsidiary of Murata (“Purchaser”). Murata is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Murata Manufacturing Co., Ltd., of Kyoto, Japan.

Pursuant to the terms and subject to the conditions set forth in the Merger Agreement, Purchaser will commence a cash tender offer (the “Offer”) to purchase all of the outstanding shares of the Company’s common stock, par value $0.001 per share (the “Shares”), at a purchase price of $4.50 per Share, net to the tendering stockholder in cash, without interest and less any required withholding taxes (the “Per Share Amount”). Upon successful completion of the Offer, and subject to the terms and conditions of the Merger Agreement, Purchaser will be merged with and into the Company (the “Merger”), and the Company will survive the Merger as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Murata. At the effective time of the Merger (the “Effective Time”), each outstanding Share (other than Shares held by (i) the Company, Murata or their respective subsidiaries immediately prior to the Effective Time and (ii) stockholders of the Company who have properly and validly perfected their statutory appraisal rights under the Delaware General Corporation Law (“DGCL”)) will automatically be converted into the right to receive the Per Share Amount on the terms and subject to the conditions set forth in the Merger Agreement. Consummation of the Offer and the Merger is not conditional on Murata’s receipt of financing.

Thanks for being the board moderator and posting updated info on the page.

Per the last CC a contract for non-mobile filter designs with a Tier 1 customer should be getting inked any day if not already. This is different than the Murata deal signed a few months ago for an upfront $7M which potentially is worth $49M.

36 million forward revenues x 10 multiple / OS is a 6 dollar handle, way undervalued here with basically no liabilities and no reason to dilute this year, last year this stock ran early in the year it should again and the technicals say it will

There are no warrants left to exercise, the issue with this stock is whether they stop selling shares under the ATM program:

“NOTE 12 - SUBSEQUENT EVENTS

Common Stock

We sold an aggregate of 2,524,200 shares of common stock under our ATM equity program between October 1, 2021 and November 10, 2021, at an average price of $2.50 per share, for gross proceeds of $6.3 million and net proceeds of $6.1 million, after deducting commissions and other offering expenses. As of November 10, 2021, we had $45.0 million available to be sold under our ATM equity program.”

“ On September 30, 2021, we entered into Addendum 1 to the collaboration agreement with Murata ("Addendum 1"), which amends and supplements the collaboration agreement to provide for the development of XBAR®-based designs for up to four additional bands. For rights to these additional bands, Murata has agreed to pay us a $4.0 million non-refundable upfront payment and up to an aggregate of between $8.0 million and $36.0 million in pre-paid royalties and other fees, with the amount of the aggregate payments determined based on the complexity of the filter designs selected for development. The future payments will be made in two installments per band over a multi-year development period, with each installment conditional upon our achievement of certain milestones and deliverables acceptable to Murata in its discretion. Murata retains the right to terminate the collaboration agreement and Addendum 1 at any time upon thirty (30) days prior written notice to us.”

“As of September 30, 2021, we have raised aggregate gross proceeds of $149.6 million through the use of loans and convertible debt, and sales of equity pursuant to our initial public offering, secondary underwritten offerings, an at-the-market equity program, private placement financings, and the exercise of stock options and warrants.

We had current assets of $20.1 million and current liabilities of $6.4 million at September 30, 2021, resulting in working capital of $13.7 million. This compares to working capital of $14.7 million at September 30, 2020 and $19.8 million at December 31, 2020.”

“At September 30, 2021 we had cash and cash equivalents of $15.3 million and accounts receivable of $4.3 million. Subsequent to September 30, 2021, but prior to the publication of the financial statements on this Form 10-Q, we raised $6.1 million of cash from sales of common stock using our At-The-Market Equity Offering Sales Agreement. In the absence of additional customer contracts, we believe these cash resources, along with anticipated cash generated from existing customer contracts, will provide sufficient funding into the fourth quarter of 2022.”

https://www.otcmarkets.com/filing/html?id=15344370&guid=_CSwkK1YE6yJnch

They have lots of Cash and millions in revenue in the form of their major customer, 36 million in contracts, so why sell shares henceforth?

Great asset/liability ratios, the SP decreased because Q3 revenues were down year over year as of September 30, but they just had a 7 million dollar payment for licensing, which is 20x Q3 revenues, and that is just one payment of many in the future, this stock should increase substantially therefore.

https://www.otcmarkets.com/filing/html?id=15344370&guid=_CSwkK1YE6yJnch

Share Structure

Market Cap Market Cap

118,279,066

01/04/2022

Authorized Shares

Not Available

Outstanding Shares

65,710,592

11/08/2021

Restricted

Not Available

Unrestricted

Not Available

Held at DTC

Not Available

Float

Not Available

Par Value

Not Available

Q4 revenues will be very high, attracting much investment in 2022:

“4:06p ET 11/10/2021 - Globe Newswire

Resonant Receives Upfront Royalty Pre-payments of $7.0 Million

Resonant Inc. (NASDAQ: RESN), a provider of radio frequency (RF) filter solutions developed on a robust intellectual property platform, designed to connect People and Things, has received payments totaling $7.0 million for initial pre-paid royalties. The payments were received pursuant to the terms of the recently expanded multi-year commercial partnership with the world's largest RF Filter manufacturer whereby Resonant's XBAR technology will be leveraged to design RF filters for next-generation networks.

"These payments are a part of a series of prepaid royalties for the first of four new RF filter designs, representing the advancement of our XBAR partnership," said George B. Holmes, Chairman and CEO of Resonant. "By expanding the strategic agreement to now include a total of eight RF filter designs, our companies are demonstrating a mutual commitment to unlock the true performance of next-generation mobile networks with innovative filters based on XBAR technology. We look forward to sharing these important partnership milestones that will continue to enhance shareholder value."

About Resonant Inc.

Resonant (NASDAQ: RESN) is transforming the market for RF front-ends (RFFE) by disrupting the RFFE supply chain through the delivery of solutions that leverage our WaveX(TM) design software tools platform, capitalize on the breadth of our IP portfolio, and are delivered through our services offerings. In a market that is critically constrained by limited designers, tools and capacity, Resonant addresses these critical problems by providing customers with ever increasing design efficiency, reduced time to market and lower unit costs. Customers leverage Resonant's disruptive capabilities to design cutting edge filters and modules, while capitalizing on the added stability of a diverse supply chain through Resonant's fabless ecosystem-the first of its kind. Working with Resonant, customers enhance the connectivity of current mobile devices, while preparing for the demands of emerging 5G applications.

To learn more about Resonant, view the series of videos published on its website that explain Resonant's technologies and market positioning:

For more information, please visit www.resonant.com.

Resonant uses its website (https://www.resonant.com) and LinkedIn page (https://www.linkedin.com/company/resonant-inc-/) as channels of distribution of information about its products, its planned financial and other announcements, its attendance at upcoming investor and industry conferences, and other matters. Such information may be deemed material information, and Resonant may use these channels to comply with its disclosure obligations under Regulation FD. Therefore, investors should monitor the company's website and its social media accounts in addition to following the company's press releases, SEC filings, public conference calls, and webcasts.

About Resonant's XBAR Filter Technology

Resonant pioneered a novel Bulk Acoustic Wave (BAW) filter technology, XBAR, to meet the challenging and complex RF front-end requirements of next-generation 5G, Wi-Fi and UWB networks and beyond. 4G BAW filter structures have traditionally been used at frequencies up to 3GHz and adapted to filter higher frequency bands, which has presented significant performance and capability challenges. Using WaveX(TM), Resonant evaluated various resonator, filter building blocks for wide-bandwidth, high-frequency and high-power filter designs. XBAR was the result of these extensive studies - the optimal next-generation filter technology.

XBAR is the first and only RF filter solution that has natively demonstrated the performance necessary to fully realize the potential of next-generation wireless technologies, including 5G and Wi-Fi 6/6E. In addition, future wireless networks will continue to move to wider bandwidths, higher frequencies and added complexity, which will further increase the demand for XBAR filters. Unlike traditional BAW filters which require complex, multi-step manufacturing processes, XBAR filters are much simpler to manufacture and hence can leverage SAW foundries.

Resonant continues to protect XBAR technology through the fundamental patents and trade secrets associated with a disruptive technology, in addition to the intellectual property associated with know-how and expertise developed subsequently.

About Resonant's WaveX(TM) Design Technology

Resonant creates designs for difficult RF frequency bands and modules that meet challenging and complex 5G, Wi-Fi and UWB RF front-end requirements. Using WaveX(TM), Resonant's designs have the potential to be developed in half the time and manufactured at a lower cost than traditional approaches. WaveX(TM) is a suite of proprietary algorithms, software design tools and network synthesis techniques that enables Resonant to explore a much larger set of possible design solutions.

Resonant delivers rapid design simulations to its customers, which they manufacture in their captive fabs or have manufactured by one of Resonant's foundry partners. These improved solutions still use Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW) or Temperature Compensated Surface Acoustic Wave (TC-SAW) technologies with the performance of higher cost manufacturing methods like Bulk Acoustic Wave (BAW).

Resonant's WaveX(TM) delivers excellent predictability, enabling achievement of the desired product performance in roughly half as many turns through the fab. In addition, Resonant's simulations model fundamental material and structure properties, which makes integration with foundry and fab customers much more intuitive, because they speak the "fab language" of basic material properties and dimensions.”

“What is a simple definition of resonance?

In physics, resonance is the tendency of a system to vibrate with increasing amplitudes at some frequencies of excitation. These are known as the system's resonant frequencies (or resonance frequencies). The resonator may have a fundamental frequency and any number of harmonics.”

https://simple.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Resonance

$RESN Resonant to Present at the Oppenheimer 5G Summit on December 14, 2021

"AUSTIN, Texas, Dec. 07, 2021 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Resonant Inc. (NASDAQ: RESN), a provider of radio frequency (RF) filter solutions developed on a robust intellectual property platform, designed to connect People and Things, today announced that management will present at the Oppenheimer 5G Summit being held virtually on Tuesday, December 14, 2021.

Resonant management will discuss how industry-leading RF filter manufacturers can leverage Resonant’s XBAR® filter technology to facilitate the transition to 5G and other next-generation, ultra-fast wireless networks, in a virtual presentation to investors during the event as follows:

Oppenheimer 5G Summit

Date: Tuesday, December 14, 2021

Time: 4:35 p.m. Eastern time (1:35 p.m. Pacific time)

Webcast: https://wsw.com/webcast/oppenheimer19/resn/2803600"

This tax loss selling is brutal. Looks like all the other 5G stocks are in the same tax sell off mode also.

$RESN Resonant Receives Upfront Royalty Pre-payments of $7.0 Million

"AUSTIN, Texas, Nov. 10, 2021 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Resonant Inc. (NASDAQ: RESN), a provider of radio frequency (RF) filter solutions developed on a robust intellectual property platform, designed to connect People and Things, has received payments totaling $7.0 million for initial pre-paid royalties. The payments were received pursuant to the terms of the recently expanded multi-year commercial partnership with the world’s largest RF Filter manufacturer whereby Resonant's XBAR® technology will be leveraged to design RF filters for next-generation networks.

“These payments are a part of a series of prepaid royalties for the first of four new RF filter designs, representing the advancement of our XBAR® partnership,” said George B. Holmes, Chairman and CEO of Resonant. “By expanding the strategic agreement to now include a total of eight RF filter designs, our companies are demonstrating a mutual commitment to unlock the true performance of next-generation mobile networks with innovative filters based on XBAR® technology. We look forward to sharing these important partnership milestones that will continue to enhance shareholder value.”

I tend to agree with "kruy post# 209"...what I don't know is how much will RESN realistically benefit from the full 5G rollout. This could be a true diamond in the ruff. Or one of those disappointing techs that got look over because of other or better solutions. Though, I am holding a position bought in back in Jan 2021. And once the true infrastructure and the real adoption takes place then we should start hearing about the contracts and royalties. I was thinking this could go the path of QCOM back in the 90's...anywho, good luck.

And I guess I do need to review its progress. It's been a while since I followed-up on RESN. Earning date tomorrow (10Nov)

https://www.resonant.com/news-resources/events/detail/1987/third-quarter-2021-financial-results-conference-call

GLTA

Resonant to Present at Upcoming Investor Conferences in November.

I hope your right! There’s a few stocks that I own that would benefit!!

True 5G doesn't exist yet as very little infrastructure to support 5G has been built. Your phone might be 5G but it is mostly running on 4G systems. Everyone is waiting for infrastructure bill to pass congress and once that does 5G stocks will take off. Chip shortage not helping 5G stocks either.

So I thought last year that this would run with 5G roll out…. Still waiting.

Resonant Inc. (RESN) Reports Q2 Loss, Tops Revenue Estimates

"Resonant Inc. (RESN) came out with a quarterly loss of $0.12 per share versus the Zacks Consensus Estimate of a loss of $0.11. This compares to loss of $0.12 per share a year ago. These figures are adjusted for non-recurring items.

This quarterly report represents an earnings surprise of -9.09%. A quarter ago, it was expected that this company would post a loss of $0.11 per share when it actually produced a loss of $0.12, delivering a surprise of -9.09%.

Over the last four quarters, the company has not been able to surpass consensus EPS estimates.

Resonant Inc.Which belongs to the Zacks Semiconductors - Radio Frequency industry, posted revenues of $0.61 million for the quarter ended June 2021, surpassing the Zacks Consensus Estimate by 2.33%. This compares to year-ago revenues of $0.6 million. The company has topped consensus revenue estimates four times over the last four quarters.

The sustainability of the stock's immediate price movement based on the recently-released numbers and future earnings expectations will mostly depend on management's commentary on the earnings call.

Resonant Inc. Shares have added about 12.5% since the beginning of the year versus the S&P 500's gain of 18.1%."

2 5G Stocks Trading Under $5; Analysts Say ‘Buy’ TipRanks

"Needham's 5-star analyst Rajvindra Gill is impressed with Resonant’s forward potential, writing, “We are still in the earliest innings of the 5G deployment cycle, with most cycles peaking 13-14 years after initial launch (2019 for 5G). The maximum potential of 5G, which is both speed and latency gains, will not be possible without new filter technology on both transmitters (base stations, routers) and receivers (consumer devices). Resonant has developed a new generation of filter that uses old production methods, which are lower cost and have a wider production base, and could gain significant traction as new filters becomes a requirement to maximize the potential of 5G globally.”

The analyst added, "The stock has underperformed the SOX... and is now trading at~10x EV/Sales on our 2022 estimate, slightly higher than its 8x 3-year median. We believe this underperformance brings an opportunity to buy shares at an attractive price, with over 100% upside... one of the largest in our coverage universe."

Unsurprisingly, Gill rates RESN a Buy, and his $6.25 price target implies a one-year upside potential of ~115%.

I think we agree despite saying it different ways. It is a dog if you are a momentum trader. In my trading account I curse it daily because I got caught too exposed. In my IRA, I want to turn that over to be managed and enjoy Belize but not till this and INDI get where they need to be. Other than that, if it's 6-9 months to get what I expect, so be it.

When I say I know the tech, I mean in the months that I was selling my house and buying land in Belize, both SWKS and RESN recruiters asked if I would do SAW filter design. I have been off in (mostly wireless) SAW and BAW sensors since I left Murata (then RF Monolithics) in 1988.

"It means the shipments have not yet crossed a minimum royalty fee level."

Yeah you understand the mechanics of royalty pay-offs much better than I do. I can only surmise from what I read and that's why I make it clear that it's only my opinion.

However, I think we are both in agreement despite our individual understanding of just how those mechanics work. I've seen posts/complaints elsewhere that because the number of units sold didn't reflect an increase in revenue (at the moment), that that somehow makes the stock a dog. If people could grasp the concept of what "royalties" actually are, how they work, and the possible effect that it could have, then they might be a little more forgiving.

The potential is here- hopefully we can both profit down the road ![]()

When you've doubled your production and your income remains the same, something is off-kilter...

"I think the revenues are recognized as earned on the prepaid revenues. I think they recognized some revenue for development milestones and some for shipments."

I agree that they receive upfront payment for the initial use of their proprietary design on a per-unit basis- as well as design milestones. But, their real income will come from royalties and that will be their steady income stream at some point in the future. I'm also pretty certain (just my opinion) that the customer(s) they are working with for their trial runs were given a pretty decent discount not to mention that the filters that their design is being used in are most likely very low-end therefore their percentage of profit on each unit is negligible. When you've doubled your production and your income remains the same, something is off-kilter...

yes you did, in the next post I read after the one I replied that to.

I think the revenues are recognized as earned on the prepaid revenues. I think they recognized some revenue for development milestones and some for shipments.

This company is at that stage where it is transitioning from sizzle to steak and everyone is hungry. dinner (concrete revenue growth) is 3-6 months out as the sales are likely to be somewhat exponential as market share increases and products go from initial pilot runs to full production.

I think the sales from the shelf registration are a lead weight for now.

I think the sales from the shelf registration are a lead weight for now.

Nice synopsis, thanks Theo.

Given the lackluster performance of this stock the last two days with the recent what appeared to be a company-hyped stellar Q update, I was forced to dig a little deeper into the DD...😏

My take (and it is MINE only), the filters being shipped by RESN's customers using WaveX technology are not generating much of an initial income impact- most likely due to the type (cheapness) of the filters being used. I have found that cell phones, for instance, contain as many as 60 different filters and they range in price (cost) from a nickle (0.05) on up. If RESN's customers are using RESN's WaveX technology on low-end filters, there won't be much up-front revenue and I think the numbers bear that out. That said, trying out new tech IS a gamble and companies looking for cutting edge advantages are not going to go out on a limb and experiment with their high-end products initially. Is this what has happened here? Don't know as I stated before- this is MY take.

My guess is RESN is relying on their XBAR technology to be the linchpin of their money generating portfolio for the future. Until then, their current revenue stream will not be recognized for some time as they are relying on royalty payments for the past two quarter sales and have not disclosed (that I can find) when or how often those payments are/will be made. *****Hence their disclosure statement on the News Release the other day: "...a majority of Resonant’s revenues are based on prepaid royalty contracts, which generate immediate cash but may have delayed revenue recognition. As a result, we continue to expect non-linear revenue amounts in subsequent quarters.

Hell, it could a year before we see recognized revenue in the quarterly statements from these initial runs of filters imo.

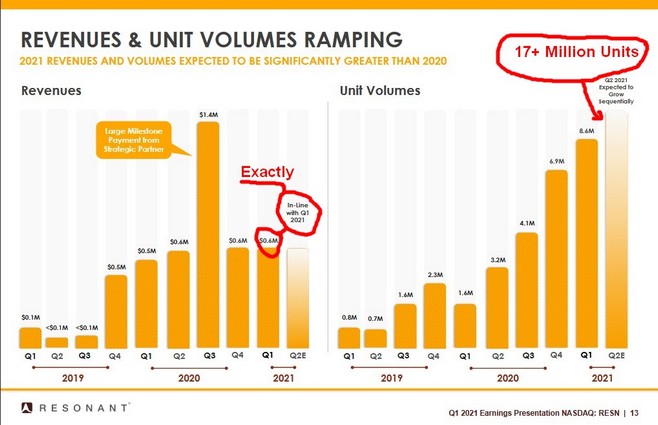

All that said, my opinion of the PR is that it only confirmed ONE thing- they ARE accurate in their time-line predictions. The pic below is from a webcast back in Q1 (?May). You can see their predictions for Q2 were spot on:

In conclusion, my take (again ONLY mine) is that there is nothing to "look" at here at the moment... we are still waiting for the big catalyst that pushes RESN over the top and this is still a development-stage company looking to break out. For the moment, I'm still satisfied with my position (avg'd @ $3.15) but more importantly, I still like the risk/reward potential. Make no mistake, the risks are significant imo. Another raise is all but guaranteed later this year based on their cash-burn imo, but could be mitigated with a strong confirmation of continued ongoing progress/success. We'll see.

The only thing I can think of at the moment is this line:

"Q2 Revenue are expected to total $0.6M, in line with the revenue reported in the same quarter a year ago." (No change in revenue YOY)

Maybe that's causing some hesitation. But it makes no sense as the last line spells it out plainly:

"As a reminder, a majority of Resonant’s revenues are based on prepaid royalty contracts, which generate immediate cash but may have delayed revenue recognition."

What's wrong with this? r they way behind schedule?

I know, bizarre right?

"Resonant slips after reporting preliminary update for Q221

Jul. 07, 2021 12:06 PM ETResonant Inc. (RESN)By: Preeti Singh, SA News Editor

Resonant (RESN -3.1%) is trading down after it provided a preliminary corporate update for Q221.

In Q2: Resonant’s customers shipped a record 17.5M radio frequency (RF) filters designed using the company’s WaveX design technology, up ~450% Y/Y and ~104% sequentially.

Over 79M RF filter units with Resonant designs have been shipped to-date.

As of June 30, 2021, Resonant's patent portfolio grew to over 350 patents, over 200 of which are related to the firm's proprietary XBAR and high frequency technologies. The company held over 300 total patents at the end of 2020 of which over 150 focused on XBAR.

Q2 Revenue are expected to total $0.6M, in line with the revenue reported in the same quarter a year ago.

As of June 30, 2021, deferred revenues are expected to be $0.8M.

The company had cash and cash equivalents of ~$22.7M by the end of June 2021.

Outlook: Resonant expects significant year-on-year revenue growth for the full year 2021.

CEO comment: "We delivered second quarter financial results in-line with previously issued guidance. Our customers cumulatively exceeded the milestone of shipping 75M RF filters designed with our WaveX technology during the second quarter, demonstrating the continued demand for our innovative RF filter designs. We are also continuing to build momentum with our XBAR technology for non-mobile applications, and we expect to secure partnerships in these high growth segments before year-end. As a reminder, a majority of Resonant’s revenues are based on prepaid royalty contracts, which generate immediate cash but may have delayed revenue recognition."

$RESN- Resonant to Present at Upcoming Investor Conferences

2021 LD Micro Invitational XI

Date: Thursday, June 10, 2021

Time: 3:30 p.m. Eastern time (12:30 p.m. Pacific time) – Track 3

Webcast: https://ldmicrojune2021.mysequire.com

Lytham Partners Summer 2021 Investor Conference

Date: Wednesday, June 16, 2021

Time: 2:45 p.m. Eastern time (11:45 a.m. Pacific time)

Webcast: https://www.webcaster4.com/Webcast/Page/2724/41495

2021 East Coast IDEAS Investor Conference

Date: Wednesday, June 16, 2021

Time: 8:00 a.m. Eastern time (5:00 a.m. Pacific time)

Webcast: www.IDEASconferences.com

$RESN White Paper Release

"Company’s white paper explores Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 6E operation in unlicensed spectrum, the challenges of signal interference, and coexistence with 5G"

3.10 should support and after the next conference 4 should break.

Picked up some AH. Will keep an eye on its movement and maybe avg down if I decide to.

between $5 and $10 now depending on sector sentiment (and growth is getting beaten up, so probably closer to $5 now). In a few quarters, well over $10 unless we go bear market.

These prices are an anti-perfect storm.

Growth stocks hammered as people look for reopening value.

Valued on trailing earnings just before it hits a nonlinear growth point.

Best in class answer to 5G and high end WiFi. Given the number of recruiters that have hit me up to become a filter designer again, the advantages of their software and design patents would make it reasonable for them to bundle licenses to designs with contract design services. Skyworks, Qorvo, RF360, and others are all facing brick walls hiring SAW/BAW filter people. Severalof them have said in their financials that that are human resource limited across their engineering needs and it is limiting growth.

been sitting on too high a % of portfolio in this at too high a price since February but utterly unconcerned. Just bored.

Where does it belong?

Tomorrow would be fine with me too but I'm more excited about the future with the even greater potential going forward.![]()

I see this into the $4's soon (tomorrow if I dare be bold, but next week after the conference is a safer bet) and back where it belongs in due course...

Resonant to Host One-On-One Meetings at the 18th Annual Craig-Hallum Institutional Investor Conference on June 2nd

"...announced that management will participate in the 18th Annual Craig-Hallum Institutional Investor Conference taking place on Wednesday, June 2, 2021."

Another one-on-one institutional investor conference... shorts took it on the chin last week after the last conference #msg-163959621

Lightning strike twice? ![]()

|

Followers

|

29

|

Posters

|

|

|

Posts (Today)

|

0

|

Posts (Total)

|

228

|

|

Created

|

07/07/14

|

Type

|

Free

|

| Moderators | |||

By Jack DentonThe U.S. aviation and telecommunications industries are waiting for regulators to assess whether the rollout of 5G poses a safety risk for aircraft.

| Volume | |

| Day Range: | |

| Bid Price | |

| Ask Price | |

| Last Trade Time: |