Wednesday, September 19, 2012 6:59:49 AM

The 47%: Who They Are, Where They Live, How They Vote, and Why They Matter

By Derek Thompson

Sep 18 2012, 1:33 AM ET

In secretly recorded comments [ http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2012/09/secret-video-romney-private-fundraiser (at {linked in} http://investorshub.advfn.com/boards/read_msg.aspx?message_id=79652529 {and preceding} and following)], Mitt Romney told a private fundraiser that the 47% of American who pay no federal income tax "dependent on government" and predicted they will "vote for the president no matter what."*

Let's not talk about what the comments mean for Romney's election chances. Let's talk about everything we know about "The 47%."

Who They Are

In 2011, 47% of Americans paid no federal income taxes. Within that group, two-thirds still pay payroll taxes. The rest are almost all either (a) old and retired folks collecting Social Security or (b) households earning less than $20,000. Overall, four out of five households not owing federal income tax earn less than $30,000, according to the Tax Policy Center [ http://taxvox.taxpolicycenter.org/2011/07/27/why-do-people-pay-no-federal-income-tax-2/ ].

(Tax Policy Center)

Here's another, slightly wonkier, way to think about the 47%. Divide the group into two halves. The first half is made tax-free by credits and exemptions, the vast majority of which go to senior citizens and children of the working poor. The half that you're left with is so poor, they wouldn't owe federal income taxes even if there were zero tax expenditures.

There are some not-so-poor outliers, like the 7,000 millionaires who paid no federal income taxes in 2011 [ http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/09/buffett-rule-rorschach-7-000-millionaires-paid-no-income-taxes-in-2011/245469/ ]. But for the most part, when you hear "The 47%" you should think "old retired folks and poor working families."

Where They Live

From David Graham [ http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2012/09/where-are-the-47-of-americans-who-pay-no-income-taxes/262499/ ], here is the graph of the 47% -- a.k.a. "non-payers" -- by state. The ten states with the highest share of "non-payers" are in the states colored red. Most are in southern (and Republican) states. Meanwhile, the 13 states with the smallest share of "non-payers" are in blue. Most are northeastern (and Democratic) states.

How They Vote

The easiest thing to say about this map is that "non-payers" ironically seem more likely to vote Republican and "payers" seem more likely to vote Democratic. But we can't say that for two reasons.

The first reason is that low income earners are much more likely to vote Democratic, even within Republican states. In 2008, Obama lost Georgia by 5 percentage points but he won 70% of voters who earned less than $30,000 [ http://super-economy.blogspot.com/2012/02/do-welfare-recipients-mostly-vote.html ] -- which is precisely the demo most likely to owe no federal income tax. Obama lost Mississippi by 14 percentage points, but picked up 66% of voters who earned less than $30,000. As a general rule, Republicans win among richer voters -- both in the red states and the blue. [Graph below via Super-Economy [ http://super-economy.blogspot.com/2012/02/do-welfare-recipients-mostly-vote.html ]]

The second factor that complicates our efforts to determine how the 47% vote is that this group is divided between older people and poorer working families. Older people vote in higher numbers. But families earning less than $20,000 voted 30% less than the national average, while households earning more than $150,000 were 30% more likely to vote than average. That data and more is in the Wikimedia Commons graph [ http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Voter_Turnout_by_Income,_2008_US_Presidential_Election.png ] below. [Editor's aside: Voter turnout is also highly correlated with variables like race, but I don't have data on the 47% broken down by those demographics.]

Why the 47% Meme Matters

Mitt Romney's off-the-record comments were inelegant. But they were also part of a long trend of Republicans attacking the 47% as lazy, or playing by a different set of rules, or not fully contributing to the country. Michele Bachmann went after the non-payers [ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/11/09/michele-bachmann-happy-meal-tax_n_1085223.html ]. So did Rick Santorum [ http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/01/the-gops-weird-obsession-with-poor-people-not-paying-enough-taxes/250928/ ]. And Sen. John Cornyn [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/why-do-half-of-all-americans-pay-no-federal-income-taxes/2011/07/11/gIQA8olBuI_blog.html ].

The 47% aren't lucky ducks cheating the system. They're mostly poor working families getting pilloried by the political party that wrote the rules they're following. If the 47% are the monster here, then Republicans helped play the role of Dr. Frankenstein. "Non-payers" have grown in the last 30 years because of marginal tax rate cuts and credits like the EITC passed under Republican presidents and continued by both parties in Congress.

It would be one thing to ask poor working families to pay higher taxes if Republicans were trying to raise money to improve government services. Quite the opposite, Romney's tax plan would, if passed, either reduce revenue or come out neutral by raising taxes on upper-middle class families. Meanwhile, his budget would gruesomely gut Medicaid and income-support programs below their projected 2020 levels.

I don't care about Romney's secret admissions. An 18-month campaign offers a downright luxurious amount of time to say dumb things. But I do care about Romney's public statements and his public stances. In February, Romney told a reporter he was "not concerned about the very poor" because they have a safety net. In August, he backed a budget that slashes the projected growth of that safety net. If only neglecting the plight of low-income families were the sort of thing Romney tried to keep a secret.

- - -

* Here's the full quote [ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XnB0NZzl5HA ]:

Copyright © 2012 by The Atlantic Monthly Group (emphasis in original)

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/the-47-who-they-are-where-they-live-how-they-vote-and-why-they-matter/262506/ [with comments]

===

A Tax Tactic That’s Open to Question

Learned Hand, the federal appeals court judge.

Alfred Eisenstaedt/Time & Life Pictures, via Getty Images

By FLOYD NORRIS

Published: September 13, 2012

“Anyone may arrange his affairs so that his taxes shall be as low as possible; he is not bound to choose that pattern which best pays the treasury. There is not even a patriotic duty to increase one’s taxes.”

— Judge Learned Hand, 1934

That quotation has become sacred to opponents of taxes, and has often been invoked this year to rebut criticism of Mitt Romney [ http://elections.nytimes.com/2012/primaries/candidates/mitt-romney ] for paying relatively low tax rates.

But nothing in it says the government is required to make it possible to avoid paying taxes. Nor does it provide that all efforts to avoid taxes are legal.

In fact, the appeals court ruling by Judge Hand [ http://www.uniset.ca/other/cs5/69F2d809.html ] concluded that the taxpayer — who had concocted an elaborate scheme to convert ordinary income into capital gains, and therefore pay less in taxes — had violated the law.

The Supreme Court unanimously upheld Judge Hand’s decision [ http://bulk.resource.org/courts.gov/c/US/293/293.US.465.127.html ]. Certainly there is a rule saying that a motive to avoid taxes is permissible, wrote Justice George Sutherland, but that was irrelevant because the strategy used by the taxpayer “upon its face lies outside the plain intent of the statute. To hold otherwise would be to exalt artifice above reality and to deprive the statutory provision in question of all serious purpose.”

There is no evidence that Mr. Romney has violated the law. The principal means he used to pay low taxes on his hundreds of millions of dollars in income was the technique known as carried interest, which allows managers of private equity [ http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/p/private_equity/index.html ] funds to treat most of the fees they receive for running the funds as capital gains rather than ordinary income.

The technique strikes some — including President Obama — as outrageous, but it is legal under current law. Unless and until the Congress changes the law, Mr. Romney has every right to take advantage of the technique.

But there is a related tactic to avoid taxes that is used by some private equity firms, including Bain Capital, whose legality is less clear. The Internal Revenue Service has not challenged it — at least not publicly — but some legal scholars say it is not justified, and some private equity firms have not chosen to use it.

The fact that Bain uses the technique became public last month when the Gawker Web site posted annual reports [ http://gawker.com/5933641 (and see {linked in} http://investorshub.advfn.com/boards/read_msg.aspx?message_id=78916119 about 40% of the way down)] from a number of Bain funds in which Mr. Romney, or his family trusts, have interests. It is clear that some Bain partners saved hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes from its use, but the Romney campaign says he did not benefit from it personally. The technique is complicated — I’ll get to the details later — but the effect is not. It concerns the management fees that sponsors of private equity funds, such as Bain Capital, are paid. Those fees are separate from the fund profits that the managers are able to treat as carried interest.

Instead of paying ordinary income taxes on those fees, the partners and employees of the fund sponsors pay taxes at much lower capital gains rates. In fact, they do even better than that. In some cases, they defer paying those capital gains taxes for years, itself a substantial benefit.

How good a deal is that? Annual reports from 2009 for four Bain funds showed that over the years the funds converted $1.05 billion in management fees from ordinary income into capital gains.

That directly benefited the Bain partners who shared in the management fees. Assuming they paid the capital gains tax of 15 percent, rather than the ordinary income tax rate of 35 percent, they saved about $210 million in income taxes and $28 million more in Medicare [ http://topics.nytimes.com/top/news/health/diseasesconditionsandhealthtopics/medicare/index.html ] taxes.

And that reflects what happened at a few funds run by one manager. All told, it is likely that private equity and venture capital fund managers save billions each year.

They do this through the technique of waiving the management fees and converting them into a preferred profit standing in the funds. The deals are structured so that they are all but certain to get the payout, assuming the fund makes money in any quarter, even if it loses money over all.

If they took the money out then — and some do — they would pay capital gains taxes immediately. But even that is more than many managers are willing to do. At many private equity funds, managers are required to put up more money, along with other investors, whenever the fund makes an acquisition. The managers use the waived management fee to make the required investment, and defer paying any taxes on it.

When that investment eventually is withdrawn, perhaps years later when the fund liquidates, the manager owes taxes on the management fee, but at the low 15 percent capital gains rate.

Some tax experts think the I.R.S. could win if it challenged the practice.

“It is not legal,” said Victor Fleisher, a tax law professor at the University of Colorado, in an interview this week. He noted that different money managers used variations, some of which he said were less likely than others to withstand an audit. “Bain,” he said, “is on the aggressive end of this.”

In an article that appeared in the journal Tax Notes in 2009 [ http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1295443 ], Gregg D. Polsky, a tax law professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law who formerly worked in the I.R.S. office of chief counsel, said he believed the I.R.S. had good arguments that would be likely to prevail in court.

In a statement issued by the Romney campaign, Brad Malt, the trustee for Romney’s blind trusts, said the tactic was “a common, accepted and totally legal practice,” although Mr. Romney had never used it personally.

One manager of private equity funds, Apollo Global Management, wants to have it both ways. As a public company, it wants to persuade investors that it has steady fee income. So it shows the waived management fees as ordinary income in the financial statements it files with the Securities and Exchange Commission. But those same reports disclose that it passes the deferred fees on to its partners and employees, who take advantage of the tax benefits.

It is quite possible that the maneuver is legal under current tax law, and that Bain and Apollo acted completely appropriately to arrange their affairs to make the taxes owed by their partners and employees as low as possible. Even if the I.R.S. and the courts eventually concluded otherwise, that would not indicate the funds had done anything wrong in asserting the position.

But it is hard for me to see the difference between that and an arrangement under which my employer invested, on my behalf, money that it would otherwise have to pay me for writing this column. Then I would tell the I.R.S. that I owed no taxes until I liquidated the investment, and even then would pay only capital gains rates.

If I tried that, I could not get away with it. If the law lets those who work in private equity do it, Congress should change the law.

At the same time, it should end the carried-interest dodge. Managers are being paid for their services when they receive a share of profits from the fund. The amount may be based on profits, but that is no different from the situation at normal companies that pay bonuses based on company earnings. It is compensation, and should be taxed as such.

Mr. Romney’s former colleagues in private equity may come to regret his candidacy, whether or not he wins. Few in the public understood this particular maneuver before the Bain reports were disclosed. Now many do. If and when Congress decides to reform the tax law, this area is likely to be a prime target.

© 2012 The New York Times Company

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/14/business/a-private-equity-tax-tactic-may-not-be-legal-high-low-finance.html [ http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/14/business/a-private-equity-tax-tactic-may-not-be-legal-high-low-finance.html?pagewanted=all ]

===

Tax Cuts Don't Lead to Economic Growth, a New 65-Year Study Finds

By Derek Thompson

Sep 16 2012, 1:53 PM ET

Here's a brief economic history of the last quarter-century in taxes and growth.

In 1990, President George H. W. Bush raised taxes, and GDP growth increased over the next five years. In 1993, President Bill Clinton raised the top marginal tax rate, and GDP growth increased over the next five years. In 2001 and 2003, President Bush cut taxes, and we faced a disappointing expansion followed by a Great Recession.

Does this story prove that raising taxes helps GDP? No. Does it prove that cutting taxes hurts GDP? No.

But it does suggest that there is a lot more to an economy than taxes, and that slashing taxes is not a guaranteed way to accelerate economic growth.

That was the conclusion from David Leonhardt's new column [ http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/16/opinion/sunday/do-tax-cuts-lead-to-economic-growth.html (next below)] today for The New York Times, and it was precisely the finding of a new study from the Congressional Research Service, "Taxes and the Economy: An Economic Analysis of the Top Tax Rates Since 1945 [ http://graphics8.nytimes.com/news/business/0915taxesandeconomy.pdf ]."

Analysis of six decades of data found that top tax rates "have had little association with saving, investment, or productivity growth." However, the study found that reductions of capital gains taxes and top marginal rate taxes have led to greater income inequality. Past studies cited in the report have suggested that a broad-based tax rate reduction can have "a small to modest, positive effect on economic growth" or "no effect on economic growth."

Well into the 1950s, the top marginal tax rate was above 90%. Today it's 35%. But both real GDP and real per capita GDP were growing more than twice as fast in the 1950s as in the 2000s. At the same time, the average tax rate paid by the top tenth of a percent fell from about 50% to 25% in the last 60 years, while their share of income increased from 4.2% in 1945 to 12.3% before the recession.

Here are two graphs of the top 0.1% and 0.01%. The first shows average tax rates since 1945 -- down, down, down. The second shows share of total income since 1945 -- up, up, up.

In short, the study found that top tax rates don't appear to determine the size of the economic pie but they can affect how the pie is sliced, especially for the richest households.

The paper is a good reminder to be humble about taxes as a tool for growing the economy. They remain, above all, a tool for collecting revenue and tweaking incentives for specific economic behavior. Congress has cut tax rates repeatedly over the last 60 years, while the country and the global economy have undergone considerable changes that probably had a greater effect on growth. For years after World War II, the U.S. was a singular economic powerhouse with an enormous manufacturing base that employed nearly 40% of the economy. For the last decade-plus, the economy has grown at a considerably slower pace and the gains have accrued to a smaller and more elite share of the economy [ http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/the-end-of-the-middle-class-century-how-the-1-won-the-last-30-years/262221/ ].

Copyright © 2012 by The Atlantic Monthly Group (emphasis in original)

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/tax-cuts-dont-lead-to-economic-growth-a-new-65-year-study-finds/262438/ [with comments]

--

Do Tax Cuts Lead to Economic Growth?

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, via Haver Analytics

The New York Times

By DAVID LEONHARDT

Published: September 15, 2012

Washington

FOR one of my occasional conversations with Representative Paul D. Ryan over the last few years, I brought a chart. The chart showed economic growth in the United States in the last several decades, and I handed Mr. Ryan a copy as we sat down in his Capitol Hill office. A self-professed economics wonk, he immediately laughed, in what seemed an appropriate mix of appreciation and teasing.

One of the first things you notice in the chart is that the American economy was not especially healthy even before the financial crisis began in late 2007. By 2007, remarkably, the economy was already on pace for its slowest decade of growth since World War II. The mediocre economic growth, in turn, brought mediocre job and income growth — and the crisis more than erased [ http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/ ] those gains.

The defining economic policy of the last decade, of course, was the Bush tax cuts. President George W. Bush and Congress, including Mr. Ryan, passed a large tax cut in 2001, sped up its implementation in 2003 and predicted that prosperity would follow.

The economic growth that actually followed — indeed, the whole history of the last 20 years — offers one of the most serious challenges to modern conservatism. Bill Clinton and the elder George Bush both raised taxes in the early 1990s, and conservatives predicted disaster. Instead, the economy boomed, and incomes grew at their fastest pace since the 1960s. Then came the younger Mr. Bush, the tax cuts, the disappointing expansion and the worst downturn since the Depression.

Today, Mitt Romney and Mr. Ryan are promising another cut in tax rates [ http://www.mittromney.com/issues/tax ] and again predicting that good times will follow. But it’s not the easiest case to make. Much as President Obama should be asked to grapple with the economy’s disappointing recent performance (a subject for a planned column), Mr. Romney and Mr. Ryan would do voters a service by explaining why a cut in tax rates would work better this time than last time.

That was precisely the question I was asking Mr. Ryan when I brought him the chart last year. He wasn’t the vice presidential nominee then, but his budget plan has a lot in common with Mr. Romney’s.

“I wouldn’t say that correlation is causation,” Mr. Ryan replied. “I would say Clinton had the tech-productivity boom, which was enormous. Trade barriers were going down in the Clinton years. He had the peace dividend he was enjoying.”

The economy in the Bush years, by contrast, had to cope with the popping of the technology bubble, 9/11, a couple of wars and the financial meltdown, Mr. Ryan continued. “Some of this is just the timing, not the person,” he said.

He then made an analogy. “Just as the Keynesians say the economy would have been worse [ http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2010/07/stimulus_0 ] without the stimulus” that Mr. Obama signed, Mr. Ryan said, “the flip side is true from our perspective.” Without the Bush tax cuts, that is, the worst economic decade since World War II would have been even worse.

Since that conversation, I have asked the same question of conservative economists and received similar answers. “To me, the Bush tax cuts get too much attention,” said R. Glenn Hubbard [ http://www.glennhubbard.net/ ], who helped design them as the chairman of Mr. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers and is now a Romney adviser. “The pro-growth elements of the tax cuts were fairly modest in size,” he added, because they also included politically minded cuts like the child tax credit. Phillip L. Swagel [ http://www.publicpolicy.umd.edu/directory/swagel ], another former Bush aide, said that even a tax cut as large as Mr. Bush’s “doesn’t translate quickly into higher growth.”

Why not? The main economic argument for tax cuts is simple enough. In the short term, they put money in people’s pockets. Longer term, people will presumably work harder if they keep more of the next dollar they earn. They will work more hours or expand their small business. This argument dominates the political debate.

But tax cuts have other effects that receive less attention — and that can slow economic growth. Somebody who cares about hitting a specific income target, like $1 million, might work less hard after receiving a tax cut. And all else equal, tax cuts increase the deficit, as Mr. Bush’s did [ http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2009/06/09/business/economy/20090610-leonhardt-graphic.html ], which creates other economic problems.

When the top marginal rate [ http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=213 ] was 70 percent or higher, as it was from 1940 to 1980, tax cuts really could make a big difference, notes Donald Marron, director of the highly regarded Tax Policy Center and another former Bush administration official. When the top rate is 35 percent, as it is today, a tax cut packs much less economic punch.

“At the level of taxes we’ve been at the last couple decades and the magnitude of the changes we’ve had, it’s hard to make the argument that tax rates have a big effect on economic growth,” Mr. Marron said. Similarly, a new report [ http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/15/tax-cuts-and-economic-growth ] from the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service found that, over the past 65 years, changes in the top tax rate “do not appear correlated with economic growth.”

Mr. Romney and Mr. Ryan, to be sure, are not calling for a simple repeat of the Bush tax cuts. They say they favor a complete overhaul of the tax code, reducing tax rates by one-fifth (taking the top rate down to 28 percent) and shrinking various tax breaks. Many economists think such an overhaul could do more good than the Bush tax cuts, by simplifying the tax code.

The problem for anyone trying to evaluate the Romney plan, however, is that there isn’t a full plan yet. He will not say [ http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/10/us/politics/romneys-tax-plan-leaves-key-variables-blank.html?pagewanted=all ] which tax breaks he would reduce, and the large ones, like the mortgage-interest deduction, are all popular. In a painstaking analysis [ http://taxpolicycenter.org/taxtopics/romney-plan.cfm ], the Tax Policy Center showed that achieving all of Mr. Romney’s top-line goals — a revenue-neutral overhaul that does not increase the tax burden of the middle class — is not arithmetically possible. History is littered with vague calls for tax reform that went nowhere.

Beyond taxes, Mr. Romney has declined to detail what spending cuts he would make, although he has promised to make big ones. And some of the programs that would be at risk — medical research, education, technology, roads, mass transportation — probably have a better historical claim [ http://thebreakthrough.org/archive/american_innovation ] on lifting economic growth than tax cuts do.

The policies that new presidents pass tend to be ones on which they laid out specifics, be they the Bush and Reagan tax cuts [ http://www.4president.org/brochures/reagan1980brochure1.htm ] or the Obama health overhaul. Based on the specifics, Mr. Romney puts a higher priority on tax cuts than anything else. Yet the reality of the last two decades has caused conservative economists, and Mr. Ryan himself, to acknowledge the limits of tax cuts.

In one of our conversations, Mr. Ryan told me that the single most important objective of any economic plan had to be raising growth. “We have to figure out how best to grow the pie so it helps everyone,” he said.

It is certainly true that strong economic growth helps solve almost every challenge the country faces: the deficit, unemployment, the income slump, even the rise of China. It is also true that some liberals put too much emphasis on the distribution of the pie and not enough on the size.

But when you dig into Mr. Romney’s and Mr. Ryan’s proposals and you consider recent history, the fairest thing to say is that, so far at least, they have laid out a plan to cut taxes. They have not yet explained why and how it is also an economic-growth plan.

David Leonhardt is the Washington bureau chief of The New York Times.

© 2012 The New York Times Company

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/16/opinion/sunday/do-tax-cuts-lead-to-economic-growth.html

===

Don’t Tell Anyone, but the Stimulus Worked

Many people benefited from projects like this one near Los Angeles but had no idea that it was part of the Obama stimulus.

Axel Koester/Corbis

Editorial | Sunday Observer

By DAVID FIRESTONE

Published: September 15, 2012

Republicans howled on Thursday when the Federal Reserve, at long last, took steps to energize the economy. Some were furious at the thought that even a little economic boost might work to benefit President Obama just before an election. “It is going to sow some growth in the economy [ http://thehill.com/business-a-lobbying/249185-republicans-question-whether-fed-carrying-water-for-obama- ],” said Raul Labrador, a freshman Tea Party congressman from Idaho, “and the Obama administration is going to claim credit.”

Mr. Labrador needn’t worry about that. The president is no more likely to get credit for the Fed’s action — for which he was not responsible — than he gets for the transformative law for which he was fully responsible: the 2009 stimulus, which fundamentally turned around the nation’s economy and its prospects for growth, and yet has disappeared from the political conversation.

The reputation of the stimulus is meticulously restored from shabby to skillful in Michael Grunwald’s important new book, “The New New Deal [ http://books.simonandschuster.com/New-New-Deal/Michael-Grunwald/9781451642322 ; http://www.amazon.com/The-New-Deal-Hidden-Change/dp/1451642326 ].” His findings will come as a jolt to those who think the law “failed,” the typical Republican assessment, or was too small and sloppy to have any effect.

On the most basic level, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act is responsible for saving and creating 2.5 million jobs. The majority of economists agree that it helped the economy grow by as much as 3.8 percent, and kept the unemployment rate from reaching 12 percent.

The stimulus is the reason, in fact, that most Americans are better off than they were four years ago, when the economy was in serious danger of shutting down.

But the stimulus did far more than stimulate: it protected the most vulnerable from the recession’s heavy winds. Of the act’s $840 billion final cost [ http://www.recovery.gov/Transparency/fundingoverview/Pages/fundingbreakdown.aspx ], $1.5 billion went to rent subsidies and emergency housing that kept 1.2 million people under roofs. (That’s why the recession didn’t produce rampant homelessness.) It increased spending on food stamps, unemployment benefits and Medicaid, keeping at least seven million Americans from falling below the poverty line.

And as Mr. Grunwald shows, it made crucial investments in neglected economic sectors that are likely to pay off for decades. It jump-started the switch to electronic medical records, which will largely end the use of paper records by 2015. It poured more than $1 billion into comparative-effectiveness research on pharmaceuticals. It extended broadband Internet to thousands of rural communities. And it spent $90 billion on a huge variety of wind, solar and other clean energy projects that revived the industry. Republicans, of course, only want to talk about Solyndra, but most of the green investments have been quite successful, and renewable power output has doubled.

Americans don’t know most of this, and not just because Mitt Romney and his party denigrate the law as a boondoggle every five minutes. Democrats, so battered by the transformation of “stimulus” into a synonym for waste and fraud (of which there was little), have stopped using the word. Only four speakers at the Democratic convention even mentioned the recovery act, none using the word stimulus.

Mr. Obama himself didn’t bring it up at all. One of the biggest accomplishments of his first term — a clear illustration of the beneficial use of government power, in a law 50 percent larger (in constant dollars) than the original New Deal — and its author doesn’t even mention it in his most widely heard re-election speech [ http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2012/09/07/remarks-president-democratic-national-convention ]. Such is the power of Republican misinformation, and Democratic timidity.

Mr. Grunwald argues that the recovery act was not timid, but the administration’s effort to sell it to the voters was muddled and ineffective. Not only did White House economists famously overestimate its impact on the jobless rate, handing Mr. Romney a favorite talking point, but the administration seemed to feel the benefits would simply be obvious. Mr. Obama, too cool to appear in an endless stream of photos with a shovel and hard hat, didn’t slap his name on public works projects in the self-promoting way of mayors and governors.

How many New Yorkers know that the stimulus is helping to pay for the Second Avenue subway, or the project to link the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central? Almost every American worker received a tax cut from the act, but only about 10 percent of them noticed it in their paychecks. White House economists had rejected the idea of distributing the tax cuts as flashy rebate checks, because people were more likely to spend the money (and help the economy) if they didn’t notice it. Good economics, perhaps, but terrible politics.

From the beginning, for purely political reasons, Republicans were determined to oppose the bill, using silly but tiny expenditures to discredit the whole thing. Even the moderate Republican senators who helped push the bill past a filibuster had refused to let it grow past $800 billion, and prevented it from paying for school construction.

Republicans learned a lesson from the stimulus that Democrats didn’t expect: unwavering opposition, distortion, deceit and ridicule actually work, especially when the opposition doesn’t put up a fight. The lesson for Democrats seems equally clear: when government actually works, let the world know about it.

© 2012 The New York Times Company

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/16/opinion/sunday/dont-tell-anyone-but-the-stimulus-worked.html

===

Wait, We're Winning the War on Poverty? A New Study Says: Absolutely

By Derek Thompson

Sep 14 2012, 8:30 AM ET

In the forty years between 1970 and 2010, real GDP per person doubled, the U.S. spent trillions of dollars on anti-poverty measures, but the poverty rate increased by two percentage points. Just yesterday the Census reported 46.2 million people living in poverty in 2011.

That's the official story. But a new paper [ http://www.nd.edu/~jsulliv4/BPEA1.6.pdf ] from Bruce D. Meyer and James X. Sullivan says it's missing everything. "We may not have won the war on poverty, but we are certainly winning," they write.

When they looked at poorer families' consumption rather than income, accounted for changes in the tax code that benefit the poor, and included "noncash benefits" such as food stamps and government-provided medical care, they found poverty fell 12.5 percentage points between 1972 and 2010.

The graph below tells the story. The official poverty rate (shown in DARK BLUE) is higher today than it was in the early 1970s. But when you measure after-tax income (RED) or consumption (GREEN), the story changes: Poverty rates have declined steadily, and dramatically, since the 1960s.

What's the story? Tax cuts for the low-income combined with tax credits for parents (such as the child tax credit) and working poor (like the Earned Income Tax Credit) accounted for much of the collapse in poverty, the authors find. Increases in Social Security also helped poverty rates fall under 10 percent by the new measure. For all the attention we give to taxes falling on the top 1% since the Reagan administration, it is equally true that effective tax rates on the bottom quintile have been halved in that time.

It sounds disastrously wrong to claim that we're winning the war on poverty 24 hours after the Census reported more people living in poverty than the combined populations of California and Missouri. But this report isn't suggesting that the war against poverty is over, merely that it is advancing. Even after a generation of stagnating market wages for men and lower-class workers, it turns out that taxing the poor less and spending more money on them is having its desired effect.

Copyright © 2012 by The Atlantic Monthly Group (emphasis in original)

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/wait-were-winning-the-war-on-poverty-a-new-study-says-absolutely/262371/ [with comments]

--

Policy Matters! Wednesday's Income, Poverty, and Insurance Coverage Data

By Jared Bernstein

Posted: 09/14/2012 9:03 am

According to new Census Bureau data released Wednesday, poverty rates as officially measured did not rise as expected last year and more people were covered by health insurance. Middle class incomes fell significantly, however, and inequality increased.

Basically, the message here is policy matters. Where policy addressed a market failure -- rising shares of the uninsured; poor families with low wages and nutritional needs -- the situation improved. Where we didn't apply policy measures to market failures -- the weak labor market on which middle-income, working families depend -- things got worse.

Health Insurance Coverage: As regards the improvement in health coverage, public policies associated with the Affordable Care Act helped to boost insurance rates of young adults.

From CBPP's statement [ http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3832 ]:

The main positive news in today's report is the fall in the share of Americans who are uninsured, from 16.3 percent in 2010 to 15.7 percent in 2011, the largest annual improvement since 1999. That improvement was driven in part by gains in coverage among young adults, which appear largely due to a provision of the health reform law allowing them to remain on their parent's health plan until they reach age 26. Forty percent of the decline in the number of uninsured people came among individuals aged 19-25. Some 539,000 fewer 19-25-year-olds were uninsured in 2011 than in 2010.

Poverty: The extent to which the safety net helped the poor is complicated by the fact that some of their most important benefits are not counted as income in the official poverty rate, which was essentially unchanged last year, falling from 15.1 percent to 15 percent. But as my colleague Arloc Sherman points out [ http://www.offthechartsblog.org/snap-food-stamps-and-earned-income-tax-credit-had-big-antipoverty-impact-in-2011/ ], these benefits actually lifted millions of households above the poverty thresholds:

The official poverty figures count only cash income, so they don't reflect the antipoverty impact of some key safety net programs, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and SNAP (formerly food stamps). But the Census data released this morning show that if you count these benefits, the EITC lifted 5.7 million people -- including 3 million children -- out of poverty in 2011, and SNAP lifted out 3.9 million people, including 1.7 million children.

Income: So what happened to middle incomes last year?

Median household income, adjusted for inflation (as are all the figures I'll cite here), fell by 1.5 percent in 2011, a loss of about $780 in 2011 dollars. This is a continuation of a pattern that began with the deep recession that began in 2007. In fact, since then, median household income is down 8 percent, or about $4,400.

Moreover, remember that incomes in the middle of the scale were flat over the 2000s business cycle, well before the recession took hold. In other words, for far too many in the middle class, income trends have devolved from stagnation to decline.

This is largely a labor market story and an inequality story. The economy expanded last year -- GDP was up 1.8 percent -- not a huge growth rate, but that's $270 billion in new output, none of which found its way to the middle class.

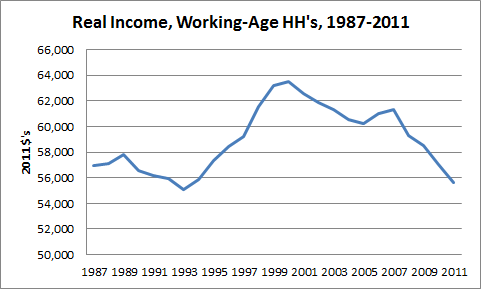

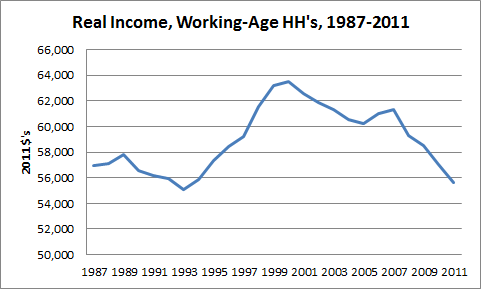

Other data from today's Census release further support this job market story. The median income of working age households, omitting retirees who depend less on labor market earnings, fell 2.4 percent last year, down $1,400 and down 9 percent -- $5,700 -- since 2007 (see figure). In fact, the level of median income for these working age households -- about $55,600 -- is about the same income level this household type had -- again, in today's dollars -- in 1993, giving back all of the gains accrued in the 1990s. Meanwhile, productivity is up 50 percent since 1993.

So where is the growth going?

Though Census data are incomplete on this point -- they include neither the capital gains that flow largely to the top of the income scale nor, as mentioned, the near cash benefits at the bottom, they still provide useful information on income inequality.

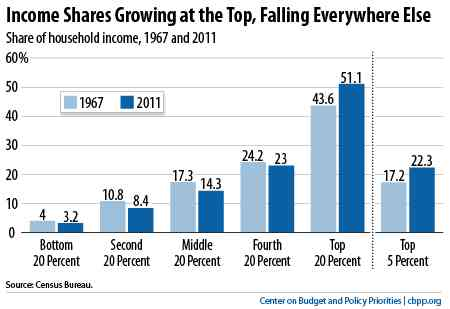

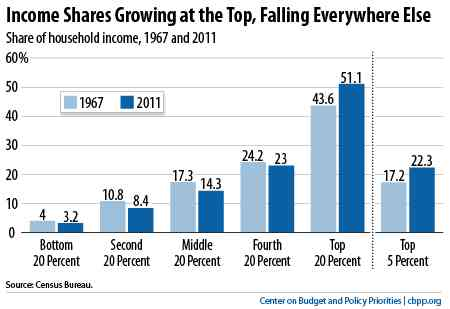

For example, the shares of the nation's income going to each of the bottom three-fifths of households were the lowest on record last year, in data that go back to 1967, while the share of income going to the top fifth was the highest on record (see figure).

The bottom 20 percent of households received just 3.2 percent of all household income in 2011, and the middle fifth of households received only 14.3 percent of the income. But the top 20 percent of households got 51.1 percent of the income in the nation, and the top 5 percent of households garnered 22.3 percent.

In short, as more of the gains of economic growth have accumulated at the top, the shares of the national income going to the bottom and middle have fallen.

It's a stark reminder that when it comes to the living standards of middle- and low-income families, overall economic growth is necessary but not sufficient. For these families to get ahead, the economy must not only expand but that expansion must reach more households, particularly those for whom growth has been largely a spectator sport.

Policy Matters: A year ago, President Obama introduced the American Jobs Act. It included fiscal relief to help states stave off these very sorts of layoffs, as well as infrastructure investments like FAST [ http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/s1597 ]!

The fact that Congress was unwilling to approve these jobs measures is one reason middle class families continue to struggle and why the growth that we are generating is doing an end run around them. In fact, if you think back to 2011, instead of debating jobs measures that could have helped middle class and low-income workers, what was Congress fighting about? Whether or not to default on the national debt. And now there's the specter of the fiscal cliff, another potential self-inflicted wound to an economy that needs a shot in the arm not a punch in the head.

These results carry two lessons. First, they pose yet another reminder to policy makers that austerity measures in an economy that remains well below potential with a job market that's still far too slack are exactly the wrong way to go. Second, they show that the economic problems we face are, in fact, amenable to policy intervention.

I'm, of course, not suggesting that the anti-poverty measures noted above are solving the market failure of poverty, nor are the few pieces of the ACA that are in place solving the challenge of health coverage. But they're both helping, and if policy makers were listening to these data, they'd recognize that such measures point the way forward.

Update: If you happened to note some different numbers on the income shares in the WaPo article [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/poverty-was-flat-in-2011-percentage-without-health-insurance-fell/2012/09/12/0e04632c-fc29-11e1-8adc-499661afe377_story.html ] on these data Wednesday, that's because the Census publishes two versions of this time series: the one that I cited above, and one in which households are adjusted for changes in family size. The historical results are the same except in the size-adjusted series, the share of income going to the lowest fifth is tied for the lowest on record.

Copyright © 2012 TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. (emphasis in original)

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jared-bernstein/policy-matters-the-new-income-poverty-and-insurance-coverage-data_b_1883573.html [with comments]

--

Is Poverty a Kind of Robbery?

By THOMAS B. EDSALL

September 16, 2012

New Haven

In her presentation on Sept. 7 at a symposium on inequality at Yale, Alice Goffman [ http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/soc/faculty/show-person.php?person_id=1335 ], an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin, talked about the winter of 2011-2012, which she spent living in Detroit among the very poor. Goffman described some of the effects of extreme poverty by quoting the words of a Detroit resident to whom she gave the pseudonym “Marqueta”:

Your fingers get slow, you know, your whole body slows down. You can’t really do much, you try to put a good face on for the kids, but when they leave you just keep still, keep the covers around you. Almost like you kind of fold into the floor. Like you’re just waiting it out. You don’t really think about too much.… November your stomach is crying at you but by December you know, you start to just shut down…. Around 3 you get up for the kids. Put the space heaters, so they come home and it’s warm in here.

There are further manifestations of the suffering on the east side of Detroit, according to Goffman:

The cold, hunger, and the depression that accompanies them both, makes for a certain moral relativism. Lots of people have written about what people become willing to do under conditions of uncertainty and extreme duress. Sailors who are lost at sea, or people in war. By the end of Detroit’s winter people become willing to do to things that they would not have considered in the more plentiful months. Like stealing, or selling their bodies.

Underneath the statistics, hidden behind the desolation of the poor in the poorest big city in the United States, lies one of most intractable political dilemmas of our era: Can the Democratic party, the party of the left, address issues of poverty and want in today’s political environment? For example, can they talk about hunger?

Hunger has grown sharply since the financial collapse of 2008, although it is felt acutely by a relatively small percentage of the population. In 2007, 12.2 percent of Americans experienced what the Department of Agriculture describes as “low food security,” including 4 percent who fell into the category of very low food security. By 2011, the percentage of those coping with low food security rose to 16.4 percent, and those experiencing very low food security went up to 5.5 percent.

The U.S.D.A. defines “low food security [ http://www.fns.usda.gov/fsec/ ]” as a lack of access “at all times to enough nutritious food for an active, healthy life.” It defines “very low food security [ http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err125.aspx ]” as individuals going without or with very little food “at times during the year because the household lacked money and other resources for food.”

Looked at through the calculus of contemporary partisan politics, the U.S.D.A. data demonstrates that in 2011 low food security was a problem for just under one in eight whites — a matter of concern but for many white voters, a virtually invisible issue. Very low food security affects the lives of only one in 24 whites.

For African Americans, low food security is a problem affecting one in four, and one in ten experience very low food security. The percentage of Hispanics who experience low food security is higher than the percentage of blacks, although the percentage of Hispanics suffering very low food security is slightly lower.

Here is the 2007 U.S.D.A. data [ http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/189485/err66.pdf ] broken down by race and ethnicity:

United States Department of Agriculture

And here is the parallel data for 2011 [ http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/884603/apn-058.pdf ]:

United States Department of Agriculture

The issue of hunger sheds light on the broader politics of poverty.

Democrats have concluded that getting enough votes on Nov. 6 precludes taking policy positions that alienate middle-class whites. In practice this means that on the campaign trail there is an absence of explicit references to the poor — and we didn’t hear much about them at the Democratic National Convention either.

Republicans, in turn, see taking a decisive majority of white votes as their best chance of winning the presidency. The 2012 electorate is likely to be 72% white, according to a number of analyses [ http://www.nationaljournal.com/thenextamerica/politics/obama-needs-80-of-minority-vote-to-win-2012-presidential-election-20120824 ]. In this scenario, Republicans need to get at least 62 percent of the white vote to win, and Democrats need to get 38 percent or more of the white vote.

Elijah Anderson [ http://www.yale.edu/sociology/faculty/pages/anderson/vitaElijahAnderson.pdf ], a sociologist at Yale and the author of several highly praised books about race and urban America, including “The Cosmopolitan Canopy,” organized the symposium. When I asked him about the Democrats’ problems in addressing poverty, Anderson wrote back in an email:

Apparently, the Republicans have backed the Democrats, and President Obama in particular, into the proverbial racial corner. It is a supreme irony that Obama, the nation’s first African-American President, finds himself unable to advocate for truly disadvantaged blacks, or even to speak out forthrightly on racial issues. To do so is to risk alienating white conservative voters, who are more than ready to scream, “we told you so,” that Obama is for “the blacks.” But it is not just the potential white voters, but the political pundits who quickly draw attention to such actions, slanting their stories to stir up racial resentment. Strikingly, blacks most often understand President Obama’s problems politically, and continue to vote for him, understanding the game full well, that Obama is doing the “best he can” in what is clearly a “deeply racist society.” It’s a conundrum.

The issue of race helps to explain another development in academia as well as in the public debate: the near abandonment of the once powerful tradition of exposing the exploitation of the poor.

Matthew Desmond [ http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/soc/faculty/desmond/index.html ], an assistant professor of sociology at Harvard, another speaker at the Yale symposium, described the extensive history of landlords, lenders and employers profiting from the rent and labor of slum dwellers. Desmond posed a question:

If exploitation long has helped to create the slum and its inhabitants, if it long has been a clear, direct, and systematic, cause of poverty and social suffering, why, then, has this ugly word — exploitation — been erased from current theories of urban poverty?

Instead, Desmond argued, contemporary urban poverty research

pivots upon the concept of a lack. Structural accounts emphasize the inner city’s lack of jobs, social services, or organizations. Cultural accounts emphasize the inner city’s lack of role models, custodial fathers, and middle-class values. Although usually pitted against one another, structural and cultural approaches share a common outlook: that the inner city is a void, a needy thing, and, like supplies lowered into the leper colony, that its problems can be solved by filing the void with more stuff: e.g., more jobs, more education, more social services.

This approach, Desmond contends, results in the misjudgment that proposals to lessen poverty by raising the minimum wage or improving welfare benefits would be sufficient. Not so, says Desmond, who spent months exploring evictions of the poor — white and black — in Milwaukee: “In a world of exploitation, such an assumption is anything but obvious.”

When Desmond began his Milwaukee fieldwork, he

wondered why middle- and upper-class landlords would buy and manage property in some of Milwaukee’s roughest neighborhoods. At the end of my fieldwork, I wondered why they wouldn’t. As Sherrena [Tarver, the pseudonym of one of the landlords he spoke to] would tell me the first time we met, “The ’hood is good. There’s a lot of money there.… A two bedroom is a two bedroom is a two bedroom. If it’s nice enough, and the people are O.K. with their living arrangements, they’re gonna take it. They are at our mercy right now. They have to have a place to stay.

At the height of the housing collapse, Tarver saw an opportunity. “This moment right now,” she told Desmond, “it’s going to create a lot of millionaires. You know, if you have money right now, you can profit from other people’s failures. … I’m catching the properties. I’m catching ‘em.”

Desmond backs up his argument — that cash transfers to the poor get siphoned off by landlords — with evidence from his study of evictions:

If Milwaukee evictions are lowest each February, it is because many members of the city’s working poor dedicate some (or all) of their Earned Income Tax Credit to pay back rent, the majority paying steep fees to receive early payments through refund anticipation loans. The E.I.T.C., it would seem, is as much a benefit to inner-city landlords and H&R Block as it is to working families. In fixating almost exclusively on what poor neighborhoods lack, social scientists and policymakers alike have overlooked a fact that never has been lost on landlords: that there is good money to be made by tapping into the riches of the slum.

Desmond makes the case for the elevation of

the concept of exploitation to a more central position within the sociology of inequality. For who could argue that the urban poor today are not just as exploited as they were in generations past, what with the acceleration of rents throughout the housing crisis; the proliferation of pawn shops, the number of which doubled in the 1990s; the emergence of the payday lending industry, boasting of more stores across the U.S. than McDonald’s restaurants and netting upwards of $7 billion annually in fees; and the colossal expansion of the subprime lending industry, which was generating upwards of $100 billion in annual revenues at the peak of the housing bubble? And yet conventional accounts of inequality, structural and cultural approaches alike, continue to view urban poverty strictly as the result of some inanity. How different our theories would be — and with them our policy prescriptions — if we began viewing poverty as the result of a kind of robbery.

Desmond’s presentation raises another question: How different would the nation’s politics be if either party, or at least the Democrats, added the concept of economic exploitation to its repertoire?

Not only would doing so risk inflaming the issue of race, but it would put at risk existing sources of campaign finance on which both parties are dependent. The finance-insurance-real estate sector is the single largest source of cash [ http://www.opensecrets.org/parties/indus.php?cycle=2012&cmte=DPC ] for the Democratic Party, $46.3 million in the current election cycle, and for the Republican Party too [ http://www.opensecrets.org/parties/indus.php?cmte=RPC&cycle=2012 ], at $67.7 million.

This dependence on moneyed interests effectively precludes exploitation as a theme for either major party to develop. These sources of campaign cash would dry up if they became the target of policies or positions they found threatening.

Even as polarization poses more sharply defined choices to the voter, pressing issues remain off limits. Poverty and hunger have been dropped from the agenda. The range of policy and electoral choices remains confined to what fits comfortably into a world of muted ethical concern, a world in which moral relativism has permeated society not so much from the bottom up, as from the top down.

The unshackling of moneyed interests — in the name of first amendment rights — from restraints on campaign contributions has, in fact, constrained the free speech of the disadvantaged. It empowers those whose goal is to hinder consumer-protection legislation, to forestall more progressive tax rates and to quash populist insurgencies.

This skewing of the odds in favor of the rich comes at a time when the Democratic Party is already inhibited by accusations that it likes to foment “class warfare” and to play “the race card.” The result has been a relentless shift of the political center from left to right. The two most recent Democratic presidents, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, have pursued agendas well within this limited terrain. There is little reason to believe that Obama, if he wins in November, will feel empowered to push out much further into territory the Democrats have virtually abandoned.

Thomas B. Edsall, a professor of journalism at Columbia University, is the author of the book “The Age of Austerity: How Scarcity Will Remake American Politics [ http://www.amazon.com/The-Age-Austerity-Scarcity-ebook/dp/B0050DIX2E ],” which was published earlier this year.

© 2012 The New York Times Company

http://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/16/is-poverty-a-kind-of-robbery/ [with comments]

===

Hating on Ben Bernanke

By PAUL KRUGMAN

Published: September 16, 2012

Last week Ben Bernanke, the Federal Reserve chairman, announced a change in his institution’s recession-fighting strategies. In so doing he seemed to be responding to the arguments of critics who have said the Fed can and should be doing more. And Republicans went wild.

Now, many people on the right have long been obsessed with the notion that we’ll be facing runaway inflation any day now. The surprise was how readily Mitt Romney joined in the craziness.

So what did Mr. Bernanke announce, and why?

The Fed normally responds to a weak economy by buying short-term U.S. government debt from banks. This adds to bank reserves; the banks go out and lend more; and the economy perks up.

Unfortunately, the scale of the financial crisis, which left behind a huge overhang of consumer debt, depressed the economy so severely that the usual channels of monetary policy don’t work. The Fed can bulk up bank reserves, but the banks have little incentive to lend the money out, because short-term interest rates are near zero. So the reserves just sit there.

The Fed’s response to this problem has been “quantitative easing,” a confusing term for buying assets other than Treasury bills, such as long-term U.S. debt. The hope has been that such purchases will drive down the cost of borrowing, and boost the economy even though conventional monetary policy has reached its limit.

Sure enough, last week’s Fed announcement included another round of quantitative easing, this time involving mortgage-backed securities. The big news, however, was the Fed’s declaration that “a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the economic recovery strengthens.” In plain English, the Fed is more or less promising that it won’t start raising interest rates as soon as the economy looks better, that it will hold off until the economy is actually booming and (perhaps) until inflation has gone significantly higher.

The idea here is that by indicating its willingness to let the economy rip for a while, the Fed can encourage more private-sector spending right away. Potential home buyers will be encouraged by the prospect of moderately higher inflation that will make their debt easier to repay; corporations will be encouraged by the prospect of higher future sales; stocks will rise, increasing wealth, and the dollar will fall, making U.S. exports more competitive.

This is very much the kind of action Fed critics have advocated — and that Mr. Bernanke himself used to advocate before he became Fed chairman. True, it’s a lot less explicit than the critics would have liked. But it’s still a welcome move, although far from being a panacea for the economy’s troubles (a point Mr. Bernanke himself emphasized).

And Republicans, as I said, have gone wild, with Mr. Romney joining in the craziness. His campaign issued a news release denouncing the Fed’s move as giving the economy an “artificial” boost — he later described it as a “sugar high” — and declaring that “we should be creating wealth, not printing dollars.”

Mr. Romney’s language echoed that of the “liquidationists” of the 1930s, who argued against doing anything to mitigate the Great Depression. Until recently, the verdict on liquidationism seemed clear: it has been rejected and ridiculed not just by liberals and Keynesians but by conservatives too, including none other than Milton Friedman. “Aggressive monetary policy can reduce the depth of a recession,” declared the George W. Bush administration in its 2004 Economic Report of the President. And the author of that report, Harvard’s N. Gregory Mankiw, has actually advocated a much more aggressive Fed policy than the one announced last week.

Now Mr. Mankiw is allegedly a Romney adviser — but the candidate’s position on economic policy is evidently being dictated by extremists who warn that any effort to fight this slump will turn us into Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe I tell you.

Oh, and what about Mr. Romney’s ideas for “creating wealth”? The Romney economic “plan” offers no specifics about what he would actually do. The thrust of it, however, is that what America needs is less environmental protection and lower taxes on the wealthy. Surprise!

Indeed, as Mike Konczal of the Roosevelt Institute points out, the Romney plan of 2012 is almost identical [ http://www.nextnewdeal.net/rortybomb/romney-will-solve-crisis-exact-same-gop-plan-2008-2006-2004 ] — and with the same turns of phrase — to John McCain’s plan in 2008, not to mention the plans laid out by George W. Bush in 2004 and 2006. The situation changes, but the song remains the same.

So last week we learned that Ben Bernanke is willing to listen to sensible critics and change course. But we also learned that on economic policy, as on foreign policy, Mitt Romney has abandoned any pose of moderation and taken up residence in the right’s intellectual fever swamps.

*

Related

Fed Ties New Aid to Jobs Recovery in Forceful Move (September 14, 2012)

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/14/business/economy/fed-announces-new-round-of-bond-buying-to-spur-growth.html

Times Topic: Federal Reserve (The Fed)

http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/organizations/f/federal_reserve_system/index.html

Related in Opinion

Editorial: The Fed Makes Its Move (September 14, 2012)

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/14/opinion/the-fed-makes-its-move.html?ref=opinion

Times Topic: Economy

http://topics.nytimes.com/top/opinion/economy/index.html

*

© 2012 The New York Times Company

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/17/opinion/krugman-hating-on-ben-bernanke.html [with comments]

--

Small business owner: QE3 is a good start, but hardly enough

By Paul Mandell

Posted at 06:00 AM ET, 09/18/2012

Under Ben Bernanke’s leadership, the Federal Reserve [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/wp/2012/09/13/qe3-is-on/ ] has worked steadily to boost our stagnant economy. With a series of incremental efforts since 2008, the Fed has tried to get us back on track, albeit with limited apparent impact.

Thursday’s announcement of a bold stimulus plan offers new hope that we are on our way out of the malaise. Perhaps most comforting is Bernanke’s indication that he and his team are shifting their focus away from inflation and squarely on the clearest path to a stronger economy — the generation of new jobs.

New jobs are the obvious fix for an immobile economy. And the best sources of those jobs are start-ups and small businesses [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/on-small-business/the-best-business-wisdom-hidden-in-classic-movie-quotes/2012/06/25/gJQA43Gm2V_story.html ]. According to the National Economic Council, over the last 20 years, start-ups and small businesses have created two-thirds of all net new jobs. And roughly half of today’s private sector employees work for small business.

The Obama Administration understands the importance of start-ups and small business, and its commitment to supporting them and their job creation efforts is evident in laws like the JOBS Act, the America Invests Act and the Affordable Care Act — all of which have had a positive impact. Thursday’s announcement is a welcome sign that, like the Obama Administration [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/on-small-business/sba-chief-defends-obamas-small-business-record-at-convention/2012/09/06/84b3ad7c-f7f4-11e1-8398-0327ab83ab91_story.html ], the Fed is now singing from the new jobs hymnal.

Unfortunately, the Fed’s actions are hardly enough to deliver a significant immediate reduction in unemployment. Keeping interest rates low for several more years will help small businesses [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/on-small-business/mere-threat-of-tax-cliff-already-weighing-heavily-on-small-businesses/2012/09/14/9313d698-fe49-11e1-8adc-499661afe377_story.html ] by preserving low borrowing costs, as well as by minimizing the opportunity cost of funding start-ups. But the potential short-term impact of the Fed’s plan seems limited, given that borrowing costs have been low for years, and given that money markets and other similar low-risk investments have provided meager returns since 2008. In short, the Fed’s new plan [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/the-full-text-of-the-federal-reserves-statement-after-its-meeting-thursday/2012/09/13/6e31bdd2-fdc1-11e1-98c6-ec0a0a93f8eb_story.html ] doesn’t change much in the short term.

For the Fed’s plan to have an impact, it must be coupled with more direct steps to enable the launch of new businesses [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/on-small-business/washington-home-to-the-most-fast-growing-firms-in-the-us/2012/09/12/c635e4c6-fcaa-11e1-b153-218509a954e1_story.html ] and more incentives for small businesses to hire.

Initiatives like the Startup America Partnership have directed more private sector capital to start-ups, and we can certainly use additional similar programs. However, the best example of the kind of help we need is the HIRE Act — a program refreshingly simple in application and potent in impact, which offered an immediate tax break [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/on-small-business/obama-plan-to-lift-top-tax-rates-would-devastate-millions-of-small-businesses-study-warns/2012/07/17/gJQAjfRkrW_story.html ] for hiring unemployed individuals. Every employer took note of this program, and it certainly gave my start-up the incentive to hire more aggressively than we would have otherwise.

By maintaining a favorable borrowing environment and setting its sights on unemployment, the Fed [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/wp/2012/08/24/will-the-feds-efforts-to-boost-the-economy-only-benefit-the-wealthiest/ ] has demonstrated both a focus on a potent contributor to our economic stagnation, as well as a commitment to addressing it. But if we want to accelerate the creation of new jobs and a reduction in unemployment, we must couple the Fed’s work with more hiring-focused offers that small business employers and start-up investors cannot refuse.

Paul Mandell is chief executive of Consero Group [ http://consero.com/ ], an event development firm in Bethesda.

© 2012 The Washington Post

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/on-small-business/post/small-business-owner-qe3-is-a-good-start-but-hardly-enough/2012/09/18/0e66ad50-fec9-11e1-a31e-804fccb658f9_blog.html [with comments]

===

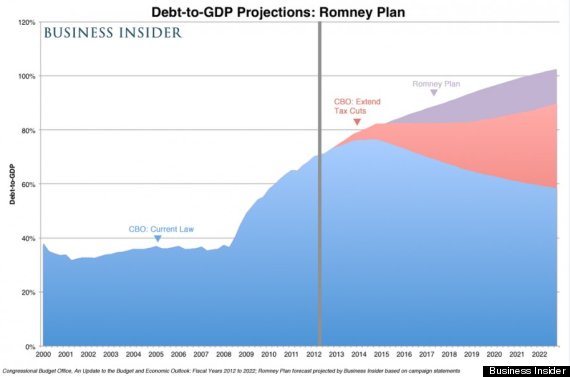

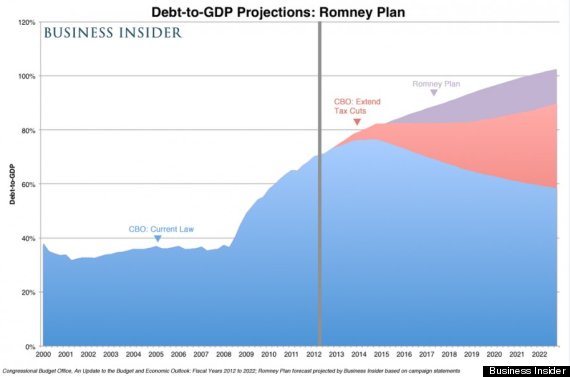

EXCLUSIVE: Romney's Plan Will Balloon The Deficit And Radically Increase The National Debt

Congressional Budget Office, An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2012 to 2022; Romney Plan forecast projected by Business Insider based on campaign statements

[ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/09/17/mitt-romney-budget-national-debt_n_1890678.html ]

Sep. 17, 2012

We have analyzed the likely impact of Mitt Romney's economic plan on the country's national debt and deficit.

Our analysis suggests that the Romney Plan will radically increase America's debt and deficits over the next 10 years.

Importantly, this is not to say that the Romney plan will be bad for the economy.

By providing additional stimulus in the form of massive government deficit spending, the plan may well reduce the unemployment rate and accelerate GDP growth faster than current law (which calls for "Fiscal Cliff" spending cuts and "Taxmageddon" tax increases early next year). If the country is to incur this much additional debt, we would prefer that such deficit spending include a major infrastructure investment and rebuilding program. But the debt growth itself may not be bad.

Based on our analysis, though, the idea that the Romney plan will ease our debt and deficit problem is laughable. Under almost any realistic scenario, it will make the problem worse.

[much more ...]

http://www.businessinsider.com/how-romney-plan-will-affect-debt-2012-9 [with comments]

===

(linked in):

http://investorshub.advfn.com/boards/read_msg.aspx?message_id=79663639 and preceding and following

http://investorshub.advfn.com/boards/read_msg.aspx?message_id=79703168 and preceding (and any future following)

By Derek Thompson

Sep 18 2012, 1:33 AM ET

In secretly recorded comments [ http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2012/09/secret-video-romney-private-fundraiser (at {linked in} http://investorshub.advfn.com/boards/read_msg.aspx?message_id=79652529 {and preceding} and following)], Mitt Romney told a private fundraiser that the 47% of American who pay no federal income tax "dependent on government" and predicted they will "vote for the president no matter what."*

Let's not talk about what the comments mean for Romney's election chances. Let's talk about everything we know about "The 47%."

Who They Are

In 2011, 47% of Americans paid no federal income taxes. Within that group, two-thirds still pay payroll taxes. The rest are almost all either (a) old and retired folks collecting Social Security or (b) households earning less than $20,000. Overall, four out of five households not owing federal income tax earn less than $30,000, according to the Tax Policy Center [ http://taxvox.taxpolicycenter.org/2011/07/27/why-do-people-pay-no-federal-income-tax-2/ ].

(Tax Policy Center)

Here's another, slightly wonkier, way to think about the 47%. Divide the group into two halves. The first half is made tax-free by credits and exemptions, the vast majority of which go to senior citizens and children of the working poor. The half that you're left with is so poor, they wouldn't owe federal income taxes even if there were zero tax expenditures.

There are some not-so-poor outliers, like the 7,000 millionaires who paid no federal income taxes in 2011 [ http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/09/buffett-rule-rorschach-7-000-millionaires-paid-no-income-taxes-in-2011/245469/ ]. But for the most part, when you hear "The 47%" you should think "old retired folks and poor working families."

Where They Live

From David Graham [ http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2012/09/where-are-the-47-of-americans-who-pay-no-income-taxes/262499/ ], here is the graph of the 47% -- a.k.a. "non-payers" -- by state. The ten states with the highest share of "non-payers" are in the states colored red. Most are in southern (and Republican) states. Meanwhile, the 13 states with the smallest share of "non-payers" are in blue. Most are northeastern (and Democratic) states.

How They Vote

The easiest thing to say about this map is that "non-payers" ironically seem more likely to vote Republican and "payers" seem more likely to vote Democratic. But we can't say that for two reasons.

The first reason is that low income earners are much more likely to vote Democratic, even within Republican states. In 2008, Obama lost Georgia by 5 percentage points but he won 70% of voters who earned less than $30,000 [ http://super-economy.blogspot.com/2012/02/do-welfare-recipients-mostly-vote.html ] -- which is precisely the demo most likely to owe no federal income tax. Obama lost Mississippi by 14 percentage points, but picked up 66% of voters who earned less than $30,000. As a general rule, Republicans win among richer voters -- both in the red states and the blue. [Graph below via Super-Economy [ http://super-economy.blogspot.com/2012/02/do-welfare-recipients-mostly-vote.html ]]

The second factor that complicates our efforts to determine how the 47% vote is that this group is divided between older people and poorer working families. Older people vote in higher numbers. But families earning less than $20,000 voted 30% less than the national average, while households earning more than $150,000 were 30% more likely to vote than average. That data and more is in the Wikimedia Commons graph [ http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Voter_Turnout_by_Income,_2008_US_Presidential_Election.png ] below. [Editor's aside: Voter turnout is also highly correlated with variables like race, but I don't have data on the 47% broken down by those demographics.]

Why the 47% Meme Matters

Mitt Romney's off-the-record comments were inelegant. But they were also part of a long trend of Republicans attacking the 47% as lazy, or playing by a different set of rules, or not fully contributing to the country. Michele Bachmann went after the non-payers [ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/11/09/michele-bachmann-happy-meal-tax_n_1085223.html ]. So did Rick Santorum [ http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/01/the-gops-weird-obsession-with-poor-people-not-paying-enough-taxes/250928/ ]. And Sen. John Cornyn [ http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/why-do-half-of-all-americans-pay-no-federal-income-taxes/2011/07/11/gIQA8olBuI_blog.html ].

The 47% aren't lucky ducks cheating the system. They're mostly poor working families getting pilloried by the political party that wrote the rules they're following. If the 47% are the monster here, then Republicans helped play the role of Dr. Frankenstein. "Non-payers" have grown in the last 30 years because of marginal tax rate cuts and credits like the EITC passed under Republican presidents and continued by both parties in Congress.

It would be one thing to ask poor working families to pay higher taxes if Republicans were trying to raise money to improve government services. Quite the opposite, Romney's tax plan would, if passed, either reduce revenue or come out neutral by raising taxes on upper-middle class families. Meanwhile, his budget would gruesomely gut Medicaid and income-support programs below their projected 2020 levels.

I don't care about Romney's secret admissions. An 18-month campaign offers a downright luxurious amount of time to say dumb things. But I do care about Romney's public statements and his public stances. In February, Romney told a reporter he was "not concerned about the very poor" because they have a safety net. In August, he backed a budget that slashes the projected growth of that safety net. If only neglecting the plight of low-income families were the sort of thing Romney tried to keep a secret.

- - -

* Here's the full quote [ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XnB0NZzl5HA ]:

"There are 47 percent of the people who will vote for the president no matter what. All right, there are 47 percent who are with him, who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it. That that's an entitlement. And the government should give it to them. And they will vote for this president no matter what...These are people who pay no income tax."

Copyright © 2012 by The Atlantic Monthly Group (emphasis in original)

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/the-47-who-they-are-where-they-live-how-they-vote-and-why-they-matter/262506/ [with comments]

===

A Tax Tactic That’s Open to Question

Learned Hand, the federal appeals court judge.

Alfred Eisenstaedt/Time & Life Pictures, via Getty Images

By FLOYD NORRIS

Published: September 13, 2012

“Anyone may arrange his affairs so that his taxes shall be as low as possible; he is not bound to choose that pattern which best pays the treasury. There is not even a patriotic duty to increase one’s taxes.”

— Judge Learned Hand, 1934

That quotation has become sacred to opponents of taxes, and has often been invoked this year to rebut criticism of Mitt Romney [ http://elections.nytimes.com/2012/primaries/candidates/mitt-romney ] for paying relatively low tax rates.

But nothing in it says the government is required to make it possible to avoid paying taxes. Nor does it provide that all efforts to avoid taxes are legal.

In fact, the appeals court ruling by Judge Hand [ http://www.uniset.ca/other/cs5/69F2d809.html ] concluded that the taxpayer — who had concocted an elaborate scheme to convert ordinary income into capital gains, and therefore pay less in taxes — had violated the law.

The Supreme Court unanimously upheld Judge Hand’s decision [ http://bulk.resource.org/courts.gov/c/US/293/293.US.465.127.html ]. Certainly there is a rule saying that a motive to avoid taxes is permissible, wrote Justice George Sutherland, but that was irrelevant because the strategy used by the taxpayer “upon its face lies outside the plain intent of the statute. To hold otherwise would be to exalt artifice above reality and to deprive the statutory provision in question of all serious purpose.”

There is no evidence that Mr. Romney has violated the law. The principal means he used to pay low taxes on his hundreds of millions of dollars in income was the technique known as carried interest, which allows managers of private equity [ http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/p/private_equity/index.html ] funds to treat most of the fees they receive for running the funds as capital gains rather than ordinary income.

The technique strikes some — including President Obama — as outrageous, but it is legal under current law. Unless and until the Congress changes the law, Mr. Romney has every right to take advantage of the technique.

But there is a related tactic to avoid taxes that is used by some private equity firms, including Bain Capital, whose legality is less clear. The Internal Revenue Service has not challenged it — at least not publicly — but some legal scholars say it is not justified, and some private equity firms have not chosen to use it.

The fact that Bain uses the technique became public last month when the Gawker Web site posted annual reports [ http://gawker.com/5933641 (and see {linked in} http://investorshub.advfn.com/boards/read_msg.aspx?message_id=78916119 about 40% of the way down)] from a number of Bain funds in which Mr. Romney, or his family trusts, have interests. It is clear that some Bain partners saved hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes from its use, but the Romney campaign says he did not benefit from it personally. The technique is complicated — I’ll get to the details later — but the effect is not. It concerns the management fees that sponsors of private equity funds, such as Bain Capital, are paid. Those fees are separate from the fund profits that the managers are able to treat as carried interest.