Friday, January 01, 2010 8:27:49 PM

Developing Wastewater Services in Emerging Market Economies: The Cases of China and Ukraine

John Bachmann, PADCO

http://www.cd3wd.com/cd3wd_40/ASDB_SMARTSAN/Bachmann.pdf

http://www.padco.aecom.com

john.bachmann@padco.aecom.com

Delivering affordable, dependable and sustainable wastewater services is a challenge for

local governments worldwide. But it is an especially tall order in emerging market

economies, in which the old service norms, institutional forms and pricing policies often

constrain the development of autonomous and competent wastewater service providers that

can develop their systems to meet users’ needs and collect sufficient revenues to cover their

costs.

China and Ukraine are two countries that are wrestling with the problems of developing

sustainable wastewater collection and disposal services while their economies transition

toward the market. This paper examines the performance of local governments and their

Wastewater Service Providers (WASPs) in selected towns in both countries and seeks to

identify the factors that contribute toward improving service quality and achieving financial

sustainability.1 The goal of the analysis is to draw conclusions that may be applicable to

WASPs in other emerging market economies.

The paper will examine in turn three aspects of wastewater service delivery — institutional

arrangements, service pricing and stakeholder participation — in each of the two countries.

For each aspect, the paper will briefly define the Chinese and Ukrainian contexts and identify

the main problems faced by WASPs and local governments (LGs). A final section will

attempt to draw conclusions about the types of interventions that could be successful in

promoting improved service delivery in the future.

Institutional Arrangements for Wastewater Service Delivery

In both China and Ukraine, wastewater service delivery is a devolved function for which local

governments are responsible. Ukraine’s law “On Local Government” of 1996 makes LGs

responsible for the provision of a number of “communal services,” including piped

wastewater collection and disposal. Most LGs execute this official mandate through

“vodokanals,” which are legally independent organizations that are nominally owned by the

local community (residents of the town or city) but in practice operate under the direction of

the local government. (A minority of vodokanals or their fixed assets are leased to private

companies.) Vodokanals are generally responsible for water supply and piped wastewater

collection and disposal.

Chinese towns are also responsible for the delivery of local wastewater services. In small

cities and towns, services are usually provided by a municipal department, often operating

independently from the water company, a municipally owned utility. In large cities,

wastewater collection and disposal services are generally carried out by municipal

departments or LG-owned water/wastewater companies.

The broad outlines of the institutional arrangements in both countries are favorable to

responsive, sustainable wastewater service delivery to the extent that local governments can

design and implement their own programs. However, the specific roles and responsibilities of

1 The material in this paper is drawn from two technical assistance projects implemented by Planning and

Development Collaborative International, Inc. (PADCO): the ADB-financed “Town-Based Urbanization Strategy

Study” (TA 4335-PRC) implemented China in 2004-2005, and the USAID-financed “Ukraine Tariff Reform and

Communal Services Enterprise Restructuring Project” implemented in 2000-2005.

the WASPs are insufficiently defined, and there are few incentives for WASP managers and

staff to improve institutional performance and/or service quality.

In the Chinese case, the operational environment for wastewater delivery is first and

foremost undermined by the political imperatives of local government leaders. In recent

years, the Government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has put heavy emphasis on

economic growth. Local government leaders — both in the Party and the town or city

government — are evaluated based on the amount of new investment they leverage and the

increase in local economic output. Prospects for promotion within the party and to larger

urban settlements will depend first and foremost on economic growth. The degree of

environmental sustainability of local growth is not an evaluation criterion. These political

priorities do not incentivize improvements in urban environmental infrastructure generally or

in wastewater service delivery in particular. On the contrary, many officials are driven to

undertake any investment project that will boost growth, regardless of its impact on the

environment.

Another constraint in Chinese towns is the dependence on decision-makers at higher levels

of government in order to improve wastewater services. Large capital investment projects

and tariff increases require approval of higher-level governments, such as a county, countylevel

city or prefecture-level city.

Finally, the performance of many Chinese WASPs is undermined by their separation from

water service providers. It is much more effective to bill customers for wastewater and water

supply services at the same time (through the same bill), given that willingness-to-pay for

water supply is always higher than willingness-to-pay for wastewater collection. The fact that

water suppliers are able to disconnect their customers in case of non-payment also

contributes to higher payment collection rates, which benefit wastewater service providers

also when billing is combined.

Unlike their Chinese counterparts, Ukrainian local have the authority to set tariffs for

wastewater services delivered by vodokanals (communal service enterprises) without

higher-level approvals. The vodokanals calculate the tariffs and make a proposal to the LG,

which approves the tariff by action of its executive committee. While the autonomy afforded

by this arrangement is an asset, it also subjects the pricing of wastewater services to the

vagaries of local government politics in an emerging democracy. Many Ukrainian mayors

feel that raising the prices of communal services will lower their chances of being reelected.

The old notions of water as a public good that the State should provide for free run deep in

Ukrainian society, especially among older people and pensioners, which make up a large

portion of the total population. It takes a progressive local government leader to decide that

raising tariffs is either (i) the right thing to do for sustainable service delivery, despite its

unpopularity, or (ii) can be fashioned into a political asset by emphasizing improvements to

service coverage or quality.

Economic growth continues to trump environmental protection in Chinese towns.

In both Ukraine and China there is a general lack of clarity about the roles and

responsibilities of WASPs vis-à-vis municipal owners and end users (customers). There are

few written agreements between local governments and wastewater service providers

specifying the responsibilities of the wastewater service provider with respect to service

levels, capital investment financing, and service pricing (tariffs). The obligations of the local

government — in effect, the LG’s contribution to improving wastewater services — are also

underarticulated: there is no specific commitment by the municipality to provide financing for

improvements, build public support for increasing payment collection, or approve necessary

tariff increases. At the same time, there are no contractual agreements between WASPs and

end users. In this operational environment, the wastewater service provider lacks clear

targets to work toward and clear commitments from the city and customers to assist in

achieving institutional and sector objectives.

Pricing of Wastewater Collection and Disposal Services

At its best, the pricing of urban services such as wastewater collection and disposal is a

complex, interdisciplinary and flexible exercise through which interested parties set prices to

achieve a set of often conflicting objectives. On the one hand, user charges should be

affordable to customers. On the other hand, tariffs should be set to ensure the level of

revenue needed to keep providing decent services in the future. Where fixed assets require

rehabilitation or coverage must be expanded, tariff revenues may have to cover capital

investment costs too. In a successful service development planning and tariff setting

process, the different parties work together to find common goals and then formulate

interventions to achieve them.

Such a “holistic” view of the tariff setting process is not yet widespread in Ukraine. In the

1990s, most municipalities, despite being responsible for service pricing, distanced

themselves from this process in order to limit perceived political damage. Cities would posit

themselves as the arbiter of the tariff setting process, a role that assumes conflicting views

among vodokanals and customers. Generally siding with the customers in order to

strengthen their position for future elections, municipal governments would generally reject

tariff increases proposed by vodokanals, thereby locking the WASPs into a downward spiral

of aging assets, rising energy costs and financial shortfalls.

Wastewater service pricing in China is also influenced by the notion of water supply (and by

association, wastewater) as a public good to which all citizens are entitled. Local

government leaders are wary of raising water and wastewater tariffs, which are consequently

below the level required for recovery of operation and maintenance (O&M) costs in most

towns.

In cities in China and Ukraine, extensive capital investment is needed to ensure adequate

future service delivery. In China, it is necessary to expand coverage of piped wastewater

collection services in response to rapid urban development and to build appropriate

wastewater treatment facilities. Ukrainian municipalities need to rebuild pumping stations

and treatment plants to reduce energy consumption and lower energy costs; moreover,

much of the aging piped network needs replacement.

Under the principle that the customer should bear as much of the cost of service provision as

possible, WASPs in both countries should calculate new tariffs that cover O&M costs and

whatever share of investment costs the end user can bear. This calculation requires

knowledge of household income and expenditures. Ability-to-pay analysis was carried out

under the USAID-financed Tariff Reform and Communal Services Enterprise Restructuring

Project in two Ukrainian cities (Lutsk and Khmelnytsky) to evaluate the impact of alternative

hypothetical tariff scenarios on household finances. The analysis concluded that there was

additional disposable income, and that it would be possible to raise water and wastewater

tariffs without surpassing the normative “15% limit” set by the local governments: combined

housing and communal services costs should not exceed 15% of the income of a household

at the 25th income percentile.

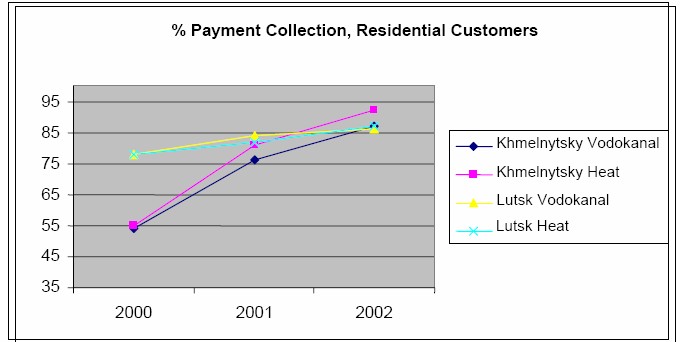

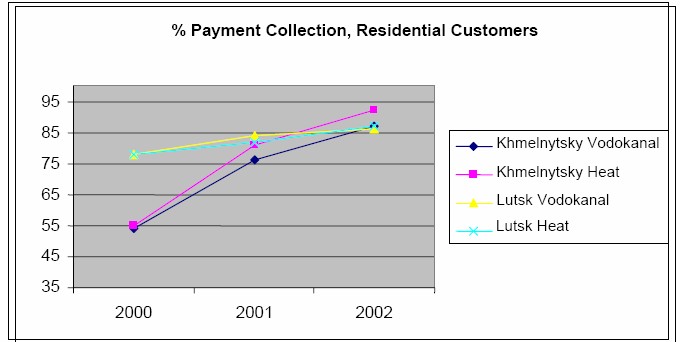

On the basis of this analysis and extensive stakeholder consultation, the City of Lutsk

decided to increase its water and wastewater tariffs by 32 percent in June 2002. In

combination with increased payment collection, the higher tariffs provided enough revenue

to cover O&M costs and finance a modest $500,000 short-term capital investment plan.

Following on the Lutsk experience, three-quarters of the 29 communal service enterprises

that graduated from the Tariff Reform Project over the period 2002–2005 achieved cost

recovery through a combination of tariff increases, higher payment collection rates and

operational cost reduction (27 enterprises were loss-making at entry into project).

Municipal public works departments and wastewater companies in China also desperately

need to raise tariffs in order to generate financing for the construction of wastewater

treatment plants. But there is no standard methodology for calculating tariffs that include a

component for O&M and another component for capital investment. And ability-to-pay

% Payment Collection, Residential Customers

35

45

55

65

75

85

95

2000 2001 2002

Khmelnytsky Vodokanal

Khmelnytsky Heat

Lutsk Vodokanal

Lutsk Heat

analysis is not used to systematically evaluate the capacity of customers to pay more.

Perhaps most critically, there is no established public forum in which packages of service

improvements and pricing options could be discussed and agreed with customers and other

stakeholders in Chinese cities in towns.

Stakeholder Participation in Wastewater Service Delivery

The Government of the PRC is currently pursuing a goal of creating a “harmonious society”

in which the benefits of growth are equitably distributed among different population groups.

Equitable distribution of the benefits of urban development requires dialogue among the

various concerned parties: local governments, real estate developers, holders of use rights

to land, buyers of newly created real estate products, and users of wastewater and other

municipally provided services. In China today, however, customers do not have a voice in

the provision of urban services. Decisions about service levels and coverage in many cities

are taken primarily based on engineering requirements and the availability of capital

investment subsidies from higher-level governments. There is no systematic consultation of

different population groups, and end user preferences and priorities are not incorporated into

the service planning and pricing process.

The investment requirements of Chinese towns and cities in the area of wastewater

treatment are staggering. If the current trend in environmental degradation of surface and

ground water supplies is to be halted, thousands of urban settlements across the country will

need to build wastewater treatment facilities. Under current conditions — an unfunded

mandate to provide services coupled with insufficient authority to increase tariffs — it would

seem difficult for Chinese WASPs to respond to the challenge. Any successful approach to

improving service levels will have to be multi-pronged, but one important aspect is likely to

be improving relations with stakeholders: the users of wastewater collection and disposal

services. In the respect, the recent experience of Ukrainian cities may prove instructive.

In the 1990s Ukraine adopted a representative democratic form of government in which

executive and legislative officials are elected at the local government level. This system

requires some degree of responsiveness to the priorities of the public on behalf of local

mayors and council deputies. But as described in the service pricing section above, elected

officials have in many cases acted as arbiters rather than leaders in the area of urban

services provision. This is now changing. Town halls in such cities as Komsomolsk,

Chernigiv, Kalush and Lutsk have forged partnerships with their communal service

enterprises (including vodokanals) and the local stakeholders.

Where such partnerships have been forged, the parties have been able to agree on and

implement substantial improvements in service delivery and sustainability. The process in

most towns has followed this general outline:

1. Build customer awareness. Conduct public outreach and carry out media campaigns to

educate the public about the need to rehabilitate or expand wastewater systems, to increase

revenues in order to pay for improvements, and to pay for services in order to ensure the

financial viability of vodokanals.

2. Gather information on customer preferences and priorities. Conduct focus groups and/or

customer surveys to find out what customers see as the major problems, what types of

service improvements are most important to them, and whether they are willing to pay more in

user charges in order to receive better services.

3. Formulate proposals that respond to customers’ stated priorities. In the process of service

planning and capital investment programming, include the projects and operational changes

that will improve coverage, improve wastewater treatment, protect local rivers and streams,

etc. Formalize these proposals into strategic action plans.

4. Garner public support for the strategic plans. Publicize the plans by distributing summary

versions of them, posting them in public places for review, and holding public hearings on the

plans.

Public hearings in Ukraine are used to build stakeholder support for wastewater

services reform.

Participants in focus groups and public hearings can be presented with different

technical/pricing options that have different sets of capital improvements associated with

them. Each option or scenario is presented as a package; for example, achieving 24 hour a

day water supply (from scheduled delivery) will necessitate a 20% tariff increase, while 24/7

water and higher water pressure above the second story will entail a 30% increase.

Participants should be able to evaluate the costs and benefits of each package themselves,

and contribute their opinion to the decision-making process.

Conclusions

This brief review of the wastewater sector in Chinese and Ukrainian towns indicates that

there is great scope for refining and improving institutional arrangements, pricing policies

and stakeholder participation. The following concrete recommendations are set out for

consideration by policy-makers and practitioners in emerging market economies.

• Reinforce the legal and regulatory basis of WASPs so that they can establish technical

service targets, plan capital investments and set prices in collaboration with local

governments and stakeholders;

• Develop and implement service agreements in which the rights and responsibilities of local

governments and WASPs are clarified. Local government commitments to achieving service

delivery targets must be spelled out clearly;

• Get the incentives right for improved performance of WASPs and LGs. Link improvements in

wastewater services and environmental protection to the career advancement among civil

servants and elected officials.

• Unite the entities responsible for water supply and wastewater collection into a single

organization responsible for both services. This will improve service planning and facilitate

tariff payment collection;

• Use ability-to-pay analysis to determine how much local households can afford to pay for

improved wastewater services;

• Use customer outreach techniques such as focus groups and customer surveys to determine

end user preferences and priorities with respect to wastewater service levels and coverage.

• Develop a tariff calculation methodology that includes a capital investment component.

• Develop and evaluate alternative capital investment and tariff scenarios with input from

stakeholders;

• Build consensus for a preferred option or scenario through information dissemination and

public hearings.

• Implement the strategic plan.

John Bachmann, PADCO

http://www.cd3wd.com/cd3wd_40/ASDB_SMARTSAN/Bachmann.pdf

http://www.padco.aecom.com

john.bachmann@padco.aecom.com

Delivering affordable, dependable and sustainable wastewater services is a challenge for

local governments worldwide. But it is an especially tall order in emerging market

economies, in which the old service norms, institutional forms and pricing policies often

constrain the development of autonomous and competent wastewater service providers that

can develop their systems to meet users’ needs and collect sufficient revenues to cover their

costs.

China and Ukraine are two countries that are wrestling with the problems of developing

sustainable wastewater collection and disposal services while their economies transition

toward the market. This paper examines the performance of local governments and their

Wastewater Service Providers (WASPs) in selected towns in both countries and seeks to

identify the factors that contribute toward improving service quality and achieving financial

sustainability.1 The goal of the analysis is to draw conclusions that may be applicable to

WASPs in other emerging market economies.

The paper will examine in turn three aspects of wastewater service delivery — institutional

arrangements, service pricing and stakeholder participation — in each of the two countries.

For each aspect, the paper will briefly define the Chinese and Ukrainian contexts and identify

the main problems faced by WASPs and local governments (LGs). A final section will

attempt to draw conclusions about the types of interventions that could be successful in

promoting improved service delivery in the future.

Institutional Arrangements for Wastewater Service Delivery

In both China and Ukraine, wastewater service delivery is a devolved function for which local

governments are responsible. Ukraine’s law “On Local Government” of 1996 makes LGs

responsible for the provision of a number of “communal services,” including piped

wastewater collection and disposal. Most LGs execute this official mandate through

“vodokanals,” which are legally independent organizations that are nominally owned by the

local community (residents of the town or city) but in practice operate under the direction of

the local government. (A minority of vodokanals or their fixed assets are leased to private

companies.) Vodokanals are generally responsible for water supply and piped wastewater

collection and disposal.

Chinese towns are also responsible for the delivery of local wastewater services. In small

cities and towns, services are usually provided by a municipal department, often operating

independently from the water company, a municipally owned utility. In large cities,

wastewater collection and disposal services are generally carried out by municipal

departments or LG-owned water/wastewater companies.

The broad outlines of the institutional arrangements in both countries are favorable to

responsive, sustainable wastewater service delivery to the extent that local governments can

design and implement their own programs. However, the specific roles and responsibilities of

1 The material in this paper is drawn from two technical assistance projects implemented by Planning and

Development Collaborative International, Inc. (PADCO): the ADB-financed “Town-Based Urbanization Strategy

Study” (TA 4335-PRC) implemented China in 2004-2005, and the USAID-financed “Ukraine Tariff Reform and

Communal Services Enterprise Restructuring Project” implemented in 2000-2005.

the WASPs are insufficiently defined, and there are few incentives for WASP managers and

staff to improve institutional performance and/or service quality.

In the Chinese case, the operational environment for wastewater delivery is first and

foremost undermined by the political imperatives of local government leaders. In recent

years, the Government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has put heavy emphasis on

economic growth. Local government leaders — both in the Party and the town or city

government — are evaluated based on the amount of new investment they leverage and the

increase in local economic output. Prospects for promotion within the party and to larger

urban settlements will depend first and foremost on economic growth. The degree of

environmental sustainability of local growth is not an evaluation criterion. These political

priorities do not incentivize improvements in urban environmental infrastructure generally or

in wastewater service delivery in particular. On the contrary, many officials are driven to

undertake any investment project that will boost growth, regardless of its impact on the

environment.

Another constraint in Chinese towns is the dependence on decision-makers at higher levels

of government in order to improve wastewater services. Large capital investment projects

and tariff increases require approval of higher-level governments, such as a county, countylevel

city or prefecture-level city.

Finally, the performance of many Chinese WASPs is undermined by their separation from

water service providers. It is much more effective to bill customers for wastewater and water

supply services at the same time (through the same bill), given that willingness-to-pay for

water supply is always higher than willingness-to-pay for wastewater collection. The fact that

water suppliers are able to disconnect their customers in case of non-payment also

contributes to higher payment collection rates, which benefit wastewater service providers

also when billing is combined.

Unlike their Chinese counterparts, Ukrainian local have the authority to set tariffs for

wastewater services delivered by vodokanals (communal service enterprises) without

higher-level approvals. The vodokanals calculate the tariffs and make a proposal to the LG,

which approves the tariff by action of its executive committee. While the autonomy afforded

by this arrangement is an asset, it also subjects the pricing of wastewater services to the

vagaries of local government politics in an emerging democracy. Many Ukrainian mayors

feel that raising the prices of communal services will lower their chances of being reelected.

The old notions of water as a public good that the State should provide for free run deep in

Ukrainian society, especially among older people and pensioners, which make up a large

portion of the total population. It takes a progressive local government leader to decide that

raising tariffs is either (i) the right thing to do for sustainable service delivery, despite its

unpopularity, or (ii) can be fashioned into a political asset by emphasizing improvements to

service coverage or quality.

Economic growth continues to trump environmental protection in Chinese towns.

In both Ukraine and China there is a general lack of clarity about the roles and

responsibilities of WASPs vis-à-vis municipal owners and end users (customers). There are

few written agreements between local governments and wastewater service providers

specifying the responsibilities of the wastewater service provider with respect to service

levels, capital investment financing, and service pricing (tariffs). The obligations of the local

government — in effect, the LG’s contribution to improving wastewater services — are also

underarticulated: there is no specific commitment by the municipality to provide financing for

improvements, build public support for increasing payment collection, or approve necessary

tariff increases. At the same time, there are no contractual agreements between WASPs and

end users. In this operational environment, the wastewater service provider lacks clear

targets to work toward and clear commitments from the city and customers to assist in

achieving institutional and sector objectives.

Pricing of Wastewater Collection and Disposal Services

At its best, the pricing of urban services such as wastewater collection and disposal is a

complex, interdisciplinary and flexible exercise through which interested parties set prices to

achieve a set of often conflicting objectives. On the one hand, user charges should be

affordable to customers. On the other hand, tariffs should be set to ensure the level of

revenue needed to keep providing decent services in the future. Where fixed assets require

rehabilitation or coverage must be expanded, tariff revenues may have to cover capital

investment costs too. In a successful service development planning and tariff setting

process, the different parties work together to find common goals and then formulate

interventions to achieve them.

Such a “holistic” view of the tariff setting process is not yet widespread in Ukraine. In the

1990s, most municipalities, despite being responsible for service pricing, distanced

themselves from this process in order to limit perceived political damage. Cities would posit

themselves as the arbiter of the tariff setting process, a role that assumes conflicting views

among vodokanals and customers. Generally siding with the customers in order to

strengthen their position for future elections, municipal governments would generally reject

tariff increases proposed by vodokanals, thereby locking the WASPs into a downward spiral

of aging assets, rising energy costs and financial shortfalls.

Wastewater service pricing in China is also influenced by the notion of water supply (and by

association, wastewater) as a public good to which all citizens are entitled. Local

government leaders are wary of raising water and wastewater tariffs, which are consequently

below the level required for recovery of operation and maintenance (O&M) costs in most

towns.

In cities in China and Ukraine, extensive capital investment is needed to ensure adequate

future service delivery. In China, it is necessary to expand coverage of piped wastewater

collection services in response to rapid urban development and to build appropriate

wastewater treatment facilities. Ukrainian municipalities need to rebuild pumping stations

and treatment plants to reduce energy consumption and lower energy costs; moreover,

much of the aging piped network needs replacement.

Under the principle that the customer should bear as much of the cost of service provision as

possible, WASPs in both countries should calculate new tariffs that cover O&M costs and

whatever share of investment costs the end user can bear. This calculation requires

knowledge of household income and expenditures. Ability-to-pay analysis was carried out

under the USAID-financed Tariff Reform and Communal Services Enterprise Restructuring

Project in two Ukrainian cities (Lutsk and Khmelnytsky) to evaluate the impact of alternative

hypothetical tariff scenarios on household finances. The analysis concluded that there was

additional disposable income, and that it would be possible to raise water and wastewater

tariffs without surpassing the normative “15% limit” set by the local governments: combined

housing and communal services costs should not exceed 15% of the income of a household

at the 25th income percentile.

On the basis of this analysis and extensive stakeholder consultation, the City of Lutsk

decided to increase its water and wastewater tariffs by 32 percent in June 2002. In

combination with increased payment collection, the higher tariffs provided enough revenue

to cover O&M costs and finance a modest $500,000 short-term capital investment plan.

Following on the Lutsk experience, three-quarters of the 29 communal service enterprises

that graduated from the Tariff Reform Project over the period 2002–2005 achieved cost

recovery through a combination of tariff increases, higher payment collection rates and

operational cost reduction (27 enterprises were loss-making at entry into project).

Municipal public works departments and wastewater companies in China also desperately

need to raise tariffs in order to generate financing for the construction of wastewater

treatment plants. But there is no standard methodology for calculating tariffs that include a

component for O&M and another component for capital investment. And ability-to-pay

% Payment Collection, Residential Customers

35

45

55

65

75

85

95

2000 2001 2002

Khmelnytsky Vodokanal

Khmelnytsky Heat

Lutsk Vodokanal

Lutsk Heat

analysis is not used to systematically evaluate the capacity of customers to pay more.

Perhaps most critically, there is no established public forum in which packages of service

improvements and pricing options could be discussed and agreed with customers and other

stakeholders in Chinese cities in towns.

Stakeholder Participation in Wastewater Service Delivery

The Government of the PRC is currently pursuing a goal of creating a “harmonious society”

in which the benefits of growth are equitably distributed among different population groups.

Equitable distribution of the benefits of urban development requires dialogue among the

various concerned parties: local governments, real estate developers, holders of use rights

to land, buyers of newly created real estate products, and users of wastewater and other

municipally provided services. In China today, however, customers do not have a voice in

the provision of urban services. Decisions about service levels and coverage in many cities

are taken primarily based on engineering requirements and the availability of capital

investment subsidies from higher-level governments. There is no systematic consultation of

different population groups, and end user preferences and priorities are not incorporated into

the service planning and pricing process.

The investment requirements of Chinese towns and cities in the area of wastewater

treatment are staggering. If the current trend in environmental degradation of surface and

ground water supplies is to be halted, thousands of urban settlements across the country will

need to build wastewater treatment facilities. Under current conditions — an unfunded

mandate to provide services coupled with insufficient authority to increase tariffs — it would

seem difficult for Chinese WASPs to respond to the challenge. Any successful approach to

improving service levels will have to be multi-pronged, but one important aspect is likely to

be improving relations with stakeholders: the users of wastewater collection and disposal

services. In the respect, the recent experience of Ukrainian cities may prove instructive.

In the 1990s Ukraine adopted a representative democratic form of government in which

executive and legislative officials are elected at the local government level. This system

requires some degree of responsiveness to the priorities of the public on behalf of local

mayors and council deputies. But as described in the service pricing section above, elected

officials have in many cases acted as arbiters rather than leaders in the area of urban

services provision. This is now changing. Town halls in such cities as Komsomolsk,

Chernigiv, Kalush and Lutsk have forged partnerships with their communal service

enterprises (including vodokanals) and the local stakeholders.

Where such partnerships have been forged, the parties have been able to agree on and

implement substantial improvements in service delivery and sustainability. The process in

most towns has followed this general outline:

1. Build customer awareness. Conduct public outreach and carry out media campaigns to

educate the public about the need to rehabilitate or expand wastewater systems, to increase

revenues in order to pay for improvements, and to pay for services in order to ensure the

financial viability of vodokanals.

2. Gather information on customer preferences and priorities. Conduct focus groups and/or

customer surveys to find out what customers see as the major problems, what types of

service improvements are most important to them, and whether they are willing to pay more in

user charges in order to receive better services.

3. Formulate proposals that respond to customers’ stated priorities. In the process of service

planning and capital investment programming, include the projects and operational changes

that will improve coverage, improve wastewater treatment, protect local rivers and streams,

etc. Formalize these proposals into strategic action plans.

4. Garner public support for the strategic plans. Publicize the plans by distributing summary

versions of them, posting them in public places for review, and holding public hearings on the

plans.

Public hearings in Ukraine are used to build stakeholder support for wastewater

services reform.

Participants in focus groups and public hearings can be presented with different

technical/pricing options that have different sets of capital improvements associated with

them. Each option or scenario is presented as a package; for example, achieving 24 hour a

day water supply (from scheduled delivery) will necessitate a 20% tariff increase, while 24/7

water and higher water pressure above the second story will entail a 30% increase.

Participants should be able to evaluate the costs and benefits of each package themselves,

and contribute their opinion to the decision-making process.

Conclusions

This brief review of the wastewater sector in Chinese and Ukrainian towns indicates that

there is great scope for refining and improving institutional arrangements, pricing policies

and stakeholder participation. The following concrete recommendations are set out for

consideration by policy-makers and practitioners in emerging market economies.

• Reinforce the legal and regulatory basis of WASPs so that they can establish technical

service targets, plan capital investments and set prices in collaboration with local

governments and stakeholders;

• Develop and implement service agreements in which the rights and responsibilities of local

governments and WASPs are clarified. Local government commitments to achieving service

delivery targets must be spelled out clearly;

• Get the incentives right for improved performance of WASPs and LGs. Link improvements in

wastewater services and environmental protection to the career advancement among civil

servants and elected officials.

• Unite the entities responsible for water supply and wastewater collection into a single

organization responsible for both services. This will improve service planning and facilitate

tariff payment collection;

• Use ability-to-pay analysis to determine how much local households can afford to pay for

improved wastewater services;

• Use customer outreach techniques such as focus groups and customer surveys to determine

end user preferences and priorities with respect to wastewater service levels and coverage.

• Develop a tariff calculation methodology that includes a capital investment component.

• Develop and evaluate alternative capital investment and tariff scenarios with input from

stakeholders;

• Build consensus for a preferred option or scenario through information dissemination and

public hearings.

• Implement the strategic plan.

Not compensated in any manner for research and/or posts. Information should be construed as information only for discussion purposes. Always conduct your own dd. Just my opinion

Join the InvestorsHub Community

Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.