Thursday, October 22, 2009 6:30:01 AM

Lost in Transmission — FDA Drug Information That Never Reaches Clinicians

http://healthcarereform.nejm.org/?p=2126&query=home#

Lisa M. Schwartz, M.D., and Steven Woloshin, M.D., October 21st, 2009

The 2009 federal stimulus package included $1.1 billion to support comparative-effectiveness research about medical treatments. No money has been allocated — and relatively little would be needed — to disseminate existing but practically inaccessible information about the benefits and harms of prescription drugs. Much critical information that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has at the time of approval may fail to make its way into the drug label and relevant journal articles.

The most direct way that the FDA communicates the prescribing information that clinicians need is through the drug label. Labels, the package inserts that come with medications, are reprinted in the Physicians’ Desk Reference and excerpted in electronic references. To ensure that labels do not exaggerate benefits or play down harms, Congress might have required that the FDA or another disinterested party write them. But it did not. Drug labels are written by drug companies, then negotiated and approved by the FDA.

When companies apply for drug approval, they submit the results of preclinical studies and usually at least two phase 3 studies — randomized clinical trials in patients with a particular condition. FDA reviewers with clinical, epidemiologic, statistical, and pharmacologic expertise spend as long as a year evaluating the evidence. FDA review documents (posted at www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/) record the reasoning behind approval decisions. Unfortunately, review documents are lengthy, inconsistently organized, and weakly summarized. But they can be fascinating, providing a sense of how reviewers struggled to decide whether benefits exceed harms. Yet in many cases, information gets lost between FDA review and the approved label.

Sometimes what gets lost is data on harms. For example, in 2001, Zometa (zoledronic acid, Novartis) was approved for use in patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy. Approval was based on the results of two trials,1 in which 287 patients with cancer were randomly assigned to receive either 4-mg or 8-mg doses of Zometa or Aredia (pamidronate), the standard of care. According to the label, 8 mg of Zometa was no more effective than 4 mg in reducing calcium levels but had greater renal toxicity (see box on Zometa data). The numbers quantifying the renal-toxicity data for the 8-mg dose did not appear in the label, as they did for the 4-mg dose. But they did appear in the 98 pages of FDA medical and statistical reviews. Surprisingly, the reviews also noted that the 8-mg dose was associated with a higher rate of death from any cause than the 4-mg dose (P=0.03). These mortality data also did not appear in the label. Nor did they appear in the journal article reporting on these studies,2 which actually recommended the 8-mg dose for refractory cases. In 2008, the FDA approved an updated Zometa label with an explicit warning statement: “Renal toxicity may be greater in patients with renal impairment. Do not use doses greater than 4 mg.” Yet the mortality data are still missing from the label.

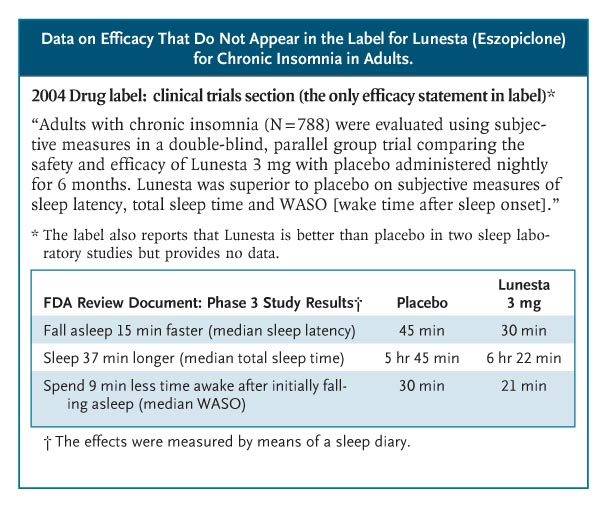

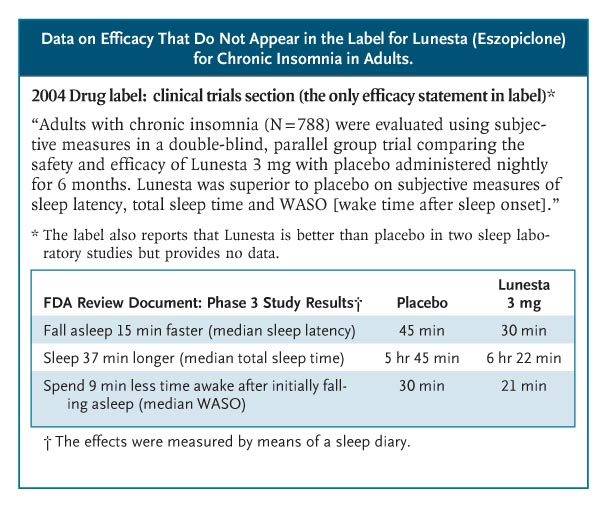

Sometimes, efficacy data get lost. Lunesta (eszopiclone) was approved in 2004 for chronic insomnia. Sepracor, its manufacturer, began an intense direct-to-consumer advertising campaign — spending more than $750,000 a day in 2007 — featuring a luna moth that transforms frustrated insomniacs into peaceful sleepers. Lunesta sales reached almost $800 million last year. Clinicians who are interested in the drug’s efficacy cannot find efficacy information in the label: it states only that Lunesta is superior to placebo (see box on Lunesta data).3 The FDA’s medical review provides efficacy data, albeit not until page 306 of the 403-page document. In the longest, largest phase 3 trial, patients in the Lunesta group reported falling asleep an average of 15 minutes faster and sleeping an average of 37 minutes longer than those in the placebo group. However, on average, Lunesta patients still met criteria for insomnia and reported no clinically meaningful improvement in next-day alertness or functioning.

A sense of uncertainty about the net benefit of drugs is almost always lost. FDA approval does not mean that a drug works well; it means only that the agency deemed its benefits to outweigh its harms. This judgment can be difficult to make: benefits may be small, important harms may not have been ruled out, and the quality of the trials may be questionable. Since the nature — or even existence — of reviewer uncertainty is not addressed in the label, clinicians cannot distinguish drugs that reviewers endorsed enthusiastically from those they viewed with great skepticism.

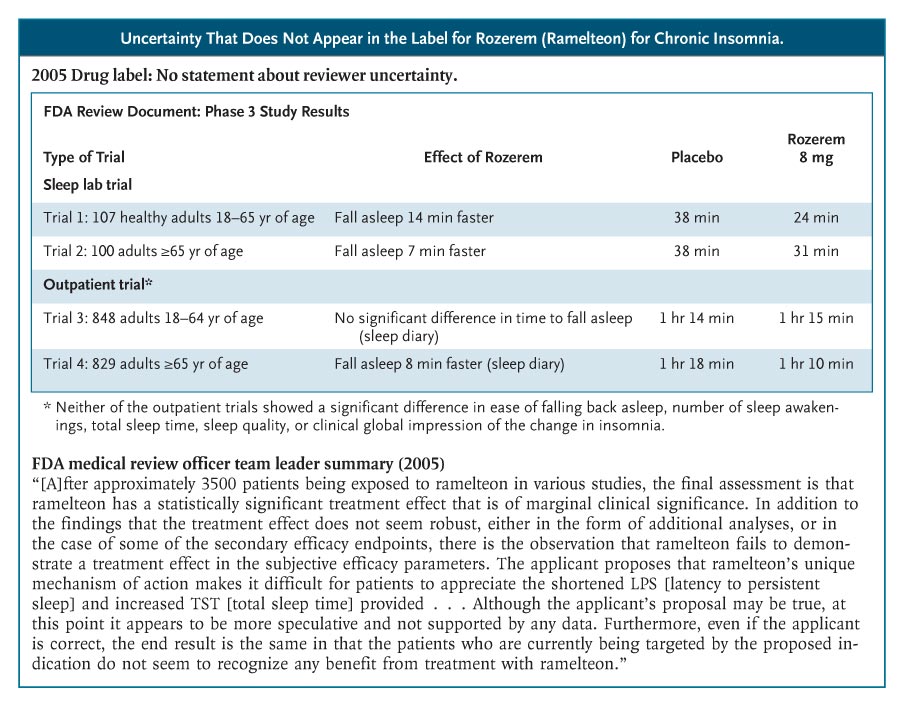

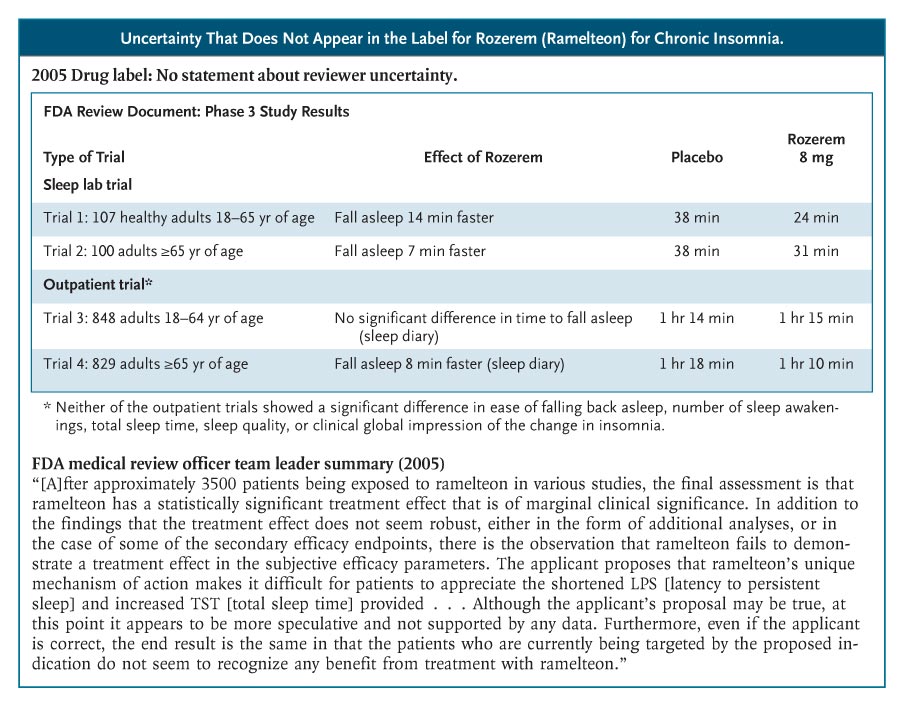

Rozerem (ramelteon), for example, was approved in 2005 for chronic insomnia and was aggressively promoted to consumers. No efficacy data were provided in the label.4 The phase 3 sleep-laboratory studies that were included in the FDA’s medical review show that Rozerem reduced the time required for patients to fall asleep (as measured by polysomnography) by 14 minutes among younger adults and by 7 minutes among older adults (see box on Rozerem data). However, there were no subjective improvements in total sleep time, sleep quality, or the time it took to fall asleep. Two phase 3 outpatient trials confirmed that people didn’t notice much benefit from Rozerem. In a trial involving younger adults, Rozerem had no effect on any subjective sleep outcome; in one involving older adults, the drug reduced reported time to fall asleep by 7 minutes but did not reduce the proportion of cases meeting the definition of insomnia (taking more than 30 minutes to fall asleep). Nor did it improve any of the secondary outcomes: falling back asleep, number of awakenings, total sleep time, or sleep quality.

The Rozerem review included a memo from the medical review team’s leader, highlighting the team’s struggle to determine whether this drug provided any clinically important benefit and whether that benefit outweighed the harms. “Ordinarily,” the memo said, “a marginally clinically significant treatment effect would not preclude an approval of a product. However, the ability to approve such a product would then focus even more on the safety profile. . . . In the case of ramelteon, there are several issues in the safety profile of concern,” including frequent symptomatic side effects and possible hyperprolactinemia. The sense that the FDA’s decision was a close call was not communicated in the label.

To its credit, the FDA has recognized problems with drug labels. In 2006, it revised the label design, adding a “highlights” section to emphasize the drug’s indications and warnings. It also issued guidance about reporting trial results in the label, emphasizing the importance of effectiveness data. Yet the data presentations for the approval studies referred to in the labels for Lunesta and Rozerem, which were updated in 2009 and 2008, respectively, are substantively unchanged.

The FDA has not issued new guidance about its drug-review documents. A standardized executive summary of the reviews would be a substantial improvement. These summaries should include data tables of the main results of the phase 3 trials, highlight reviewers’ uncertainties, and note whether approval was conditional on a post-approval study.

Toward this goal, we conducted a pilot test, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Pioneer Portfolio, in which FDA reviewers created “Prescription Drug Facts Boxes,”5 featuring a data table of benefits and harms. Recently, the FDA’s Risk Advisory Committee recommended that the FDA adopt these boxes as the standard for their communications. FDA leadership is deciding whether and how to use the boxes in reviews, labels, or both.

Whatever approach the agency adopts, it needs a better way of communicating drug information to clinicians. We don’t need to wait for new comparative-effectiveness results in order to improve practice. We need to better disseminate what is already known.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

Source Information

From the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Hanover, NH; and the VA Outcomes Group, VA Medical Center, White River Junction, VT.

This article (10.1056/NEJMp0907708) was published on October 21, 2009, at NEJM.org.

References

1. Drugs@FDA. Approval history of NDA 021223: Zometa. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration. (Accessed October 8, 2009, at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/DrugsatFDA/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory#apphist.)

2. Major P, Lortholary A, Hon J, et al. Zoledronic acid is superior to pamidronate in the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy: a pooled analysis of two randomized, controlled clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:558-567. [Free Full Text]

3. Drugs@FDA. Approval history of NDA 021476: Lunesta. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration. (Accessed October 8, 2009, at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/DrugsatFDA/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory#apphist.)

4. Drugs@FDA. Approval history of NDA 021782: Rozerem. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration. (Accessed October 8, 2009, at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/DrugsatFDA/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory#apphist.)

5. Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Welch HG. Using a drug facts box to communicate drug benefits and harms: two randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:516-527. [Free Full Text]

http://healthcarereform.nejm.org/?p=2126&query=home#

Lisa M. Schwartz, M.D., and Steven Woloshin, M.D., October 21st, 2009

The 2009 federal stimulus package included $1.1 billion to support comparative-effectiveness research about medical treatments. No money has been allocated — and relatively little would be needed — to disseminate existing but practically inaccessible information about the benefits and harms of prescription drugs. Much critical information that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has at the time of approval may fail to make its way into the drug label and relevant journal articles.

The most direct way that the FDA communicates the prescribing information that clinicians need is through the drug label. Labels, the package inserts that come with medications, are reprinted in the Physicians’ Desk Reference and excerpted in electronic references. To ensure that labels do not exaggerate benefits or play down harms, Congress might have required that the FDA or another disinterested party write them. But it did not. Drug labels are written by drug companies, then negotiated and approved by the FDA.

When companies apply for drug approval, they submit the results of preclinical studies and usually at least two phase 3 studies — randomized clinical trials in patients with a particular condition. FDA reviewers with clinical, epidemiologic, statistical, and pharmacologic expertise spend as long as a year evaluating the evidence. FDA review documents (posted at www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/) record the reasoning behind approval decisions. Unfortunately, review documents are lengthy, inconsistently organized, and weakly summarized. But they can be fascinating, providing a sense of how reviewers struggled to decide whether benefits exceed harms. Yet in many cases, information gets lost between FDA review and the approved label.

Sometimes what gets lost is data on harms. For example, in 2001, Zometa (zoledronic acid, Novartis) was approved for use in patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy. Approval was based on the results of two trials,1 in which 287 patients with cancer were randomly assigned to receive either 4-mg or 8-mg doses of Zometa or Aredia (pamidronate), the standard of care. According to the label, 8 mg of Zometa was no more effective than 4 mg in reducing calcium levels but had greater renal toxicity (see box on Zometa data). The numbers quantifying the renal-toxicity data for the 8-mg dose did not appear in the label, as they did for the 4-mg dose. But they did appear in the 98 pages of FDA medical and statistical reviews. Surprisingly, the reviews also noted that the 8-mg dose was associated with a higher rate of death from any cause than the 4-mg dose (P=0.03). These mortality data also did not appear in the label. Nor did they appear in the journal article reporting on these studies,2 which actually recommended the 8-mg dose for refractory cases. In 2008, the FDA approved an updated Zometa label with an explicit warning statement: “Renal toxicity may be greater in patients with renal impairment. Do not use doses greater than 4 mg.” Yet the mortality data are still missing from the label.

Sometimes, efficacy data get lost. Lunesta (eszopiclone) was approved in 2004 for chronic insomnia. Sepracor, its manufacturer, began an intense direct-to-consumer advertising campaign — spending more than $750,000 a day in 2007 — featuring a luna moth that transforms frustrated insomniacs into peaceful sleepers. Lunesta sales reached almost $800 million last year. Clinicians who are interested in the drug’s efficacy cannot find efficacy information in the label: it states only that Lunesta is superior to placebo (see box on Lunesta data).3 The FDA’s medical review provides efficacy data, albeit not until page 306 of the 403-page document. In the longest, largest phase 3 trial, patients in the Lunesta group reported falling asleep an average of 15 minutes faster and sleeping an average of 37 minutes longer than those in the placebo group. However, on average, Lunesta patients still met criteria for insomnia and reported no clinically meaningful improvement in next-day alertness or functioning.

A sense of uncertainty about the net benefit of drugs is almost always lost. FDA approval does not mean that a drug works well; it means only that the agency deemed its benefits to outweigh its harms. This judgment can be difficult to make: benefits may be small, important harms may not have been ruled out, and the quality of the trials may be questionable. Since the nature — or even existence — of reviewer uncertainty is not addressed in the label, clinicians cannot distinguish drugs that reviewers endorsed enthusiastically from those they viewed with great skepticism.

Rozerem (ramelteon), for example, was approved in 2005 for chronic insomnia and was aggressively promoted to consumers. No efficacy data were provided in the label.4 The phase 3 sleep-laboratory studies that were included in the FDA’s medical review show that Rozerem reduced the time required for patients to fall asleep (as measured by polysomnography) by 14 minutes among younger adults and by 7 minutes among older adults (see box on Rozerem data). However, there were no subjective improvements in total sleep time, sleep quality, or the time it took to fall asleep. Two phase 3 outpatient trials confirmed that people didn’t notice much benefit from Rozerem. In a trial involving younger adults, Rozerem had no effect on any subjective sleep outcome; in one involving older adults, the drug reduced reported time to fall asleep by 7 minutes but did not reduce the proportion of cases meeting the definition of insomnia (taking more than 30 minutes to fall asleep). Nor did it improve any of the secondary outcomes: falling back asleep, number of awakenings, total sleep time, or sleep quality.

The Rozerem review included a memo from the medical review team’s leader, highlighting the team’s struggle to determine whether this drug provided any clinically important benefit and whether that benefit outweighed the harms. “Ordinarily,” the memo said, “a marginally clinically significant treatment effect would not preclude an approval of a product. However, the ability to approve such a product would then focus even more on the safety profile. . . . In the case of ramelteon, there are several issues in the safety profile of concern,” including frequent symptomatic side effects and possible hyperprolactinemia. The sense that the FDA’s decision was a close call was not communicated in the label.

To its credit, the FDA has recognized problems with drug labels. In 2006, it revised the label design, adding a “highlights” section to emphasize the drug’s indications and warnings. It also issued guidance about reporting trial results in the label, emphasizing the importance of effectiveness data. Yet the data presentations for the approval studies referred to in the labels for Lunesta and Rozerem, which were updated in 2009 and 2008, respectively, are substantively unchanged.

The FDA has not issued new guidance about its drug-review documents. A standardized executive summary of the reviews would be a substantial improvement. These summaries should include data tables of the main results of the phase 3 trials, highlight reviewers’ uncertainties, and note whether approval was conditional on a post-approval study.

Toward this goal, we conducted a pilot test, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Pioneer Portfolio, in which FDA reviewers created “Prescription Drug Facts Boxes,”5 featuring a data table of benefits and harms. Recently, the FDA’s Risk Advisory Committee recommended that the FDA adopt these boxes as the standard for their communications. FDA leadership is deciding whether and how to use the boxes in reviews, labels, or both.

Whatever approach the agency adopts, it needs a better way of communicating drug information to clinicians. We don’t need to wait for new comparative-effectiveness results in order to improve practice. We need to better disseminate what is already known.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

Source Information

From the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Hanover, NH; and the VA Outcomes Group, VA Medical Center, White River Junction, VT.

This article (10.1056/NEJMp0907708) was published on October 21, 2009, at NEJM.org.

References

1. Drugs@FDA. Approval history of NDA 021223: Zometa. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration. (Accessed October 8, 2009, at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/DrugsatFDA/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory#apphist.)

2. Major P, Lortholary A, Hon J, et al. Zoledronic acid is superior to pamidronate in the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy: a pooled analysis of two randomized, controlled clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:558-567. [Free Full Text]

3. Drugs@FDA. Approval history of NDA 021476: Lunesta. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration. (Accessed October 8, 2009, at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/DrugsatFDA/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory#apphist.)

4. Drugs@FDA. Approval history of NDA 021782: Rozerem. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration. (Accessed October 8, 2009, at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/DrugsatFDA/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory#apphist.)

5. Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Welch HG. Using a drug facts box to communicate drug benefits and harms: two randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:516-527. [Free Full Text]

Join the InvestorsHub Community

Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.