| Followers | 680 |

| Posts | 141062 |

| Boards Moderated | 36 |

| Alias Born | 03/10/2004 |

Saturday, January 19, 2019 10:01:56 AM

Bull in the China Shop

By: John Mauldin | January 18, 2019

Demand Pulled Forward

The 2008 financial crisis and recession hit China hard, as it did everyone else. Not every country responded like China did, though. Most couldn’t do what China did because they lacked either the financial resources or the political ability. China had both, and so launched a stimulus program of mind-boggling proportions. Beijing compelled local governments and state-owned enterprises to take on massive debt for giant infrastructure projects, huge capacity expansions, and pretty much anything else they could imagine that would put people to work and bolster public confidence. Yes, they built ghost cities.

(Incidentally, the classic ghost city was in Mongolia, literally vacant for a time but now well on its way to being fully occupied or bought. Long game and deep pockets, indeed.)

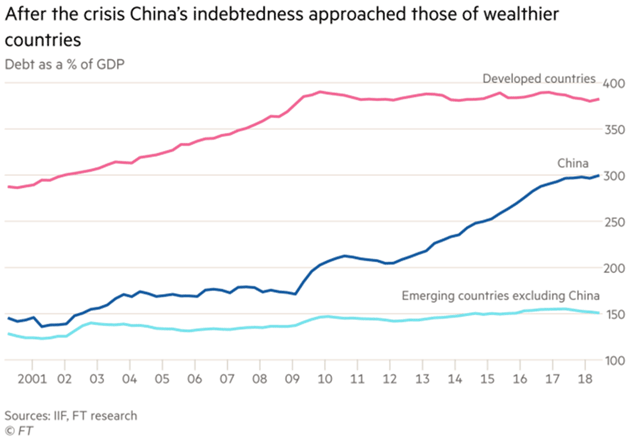

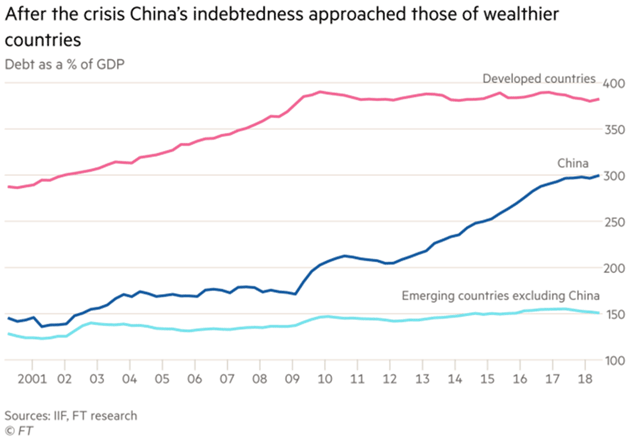

Not coincidentally, China has doubled its debt relative to GDP since the beginning of the century, and the bulk of that was after 2009.

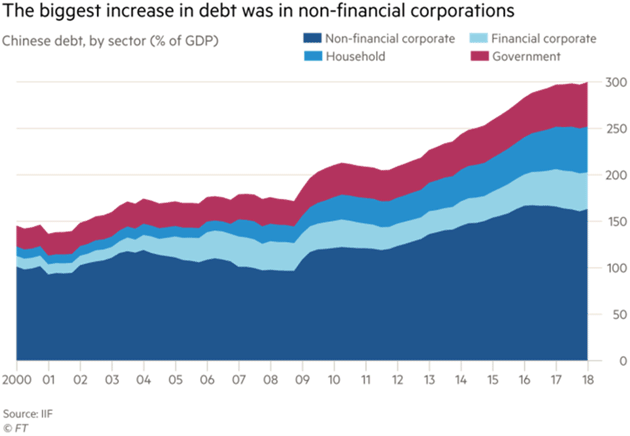

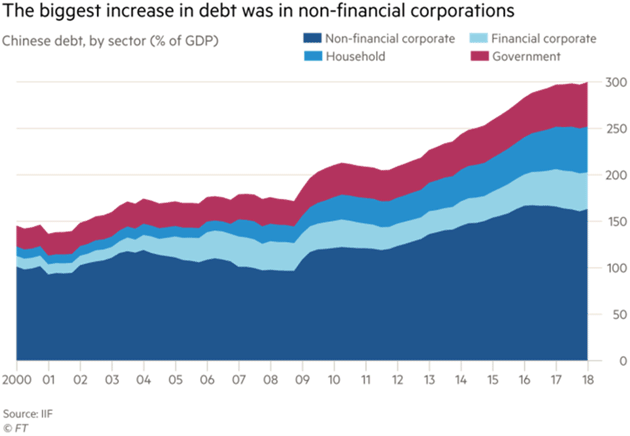

But it’s how they grew that debt I find amazing. We must remember that the Chinese economy is managed from the top down. The Chinese government is very aware of how its shadow banking system operates. Half of the total debt is from the nonfinancial (i.e., shadow banks) sector. And while Simon Hunt talks about deleveraging, when I talked with him what he really means is that the Chinese government is trying to move from Wild West shadow banking to more traditional bank financing. Central bankers sometimes accompany private bankers to meet loan-seeking businesses. Chinese characteristics, indeed.

In my research for this letter I came across several mentions that China is planning to move another 150 million rural citizens to urban areas, many into so-called second-tier cities. Only in China can a second-tier city have five million people. And people moving from the country into the city becomes far more productive in terms of GDP. And China is beginning to focus on upgrading the infrastructure and the rural cities as well.

As the entire world will come to realize in the middle of the next decade, the debt which financed that infrastructure does have a carrying cost. Even in a top-down economy. Yes, much of it is internal but our first concern is China’s enormous amount of dollar-denominated debt. Here’s Christopher Balding with the numbers:

According to official data, short-term debt accounted for 62 percent of the total [of almost $2 trillion in debt] as of September, meaning that $1.2 trillion will have to be rolled over this year. Just as worrying is the speed of increase: Total external debt has increased 14 percent in the past year and 35 percent since the beginning of 2017.

External debt is no longer a trivial slice of China’s foreign-exchange reserves, which stood at just over $3 trillion at the end of November, little changed from two years earlier. Short-term foreign debt increased to 39 percent of reserves in September, from 26 percent in March 2016.

The true picture may be more precarious. China’s external debt was estimated between $3 trillion and $3.5 trillion by Daiwa Capital Markets in an August report. In other words, total foreign liabilities could be understated by as much as $1.5 trillion after accounting for borrowing in financial centres such as Hong Kong, New York, and the Caribbean islands that isn’t included in the official tally.

So, China could owe non-Chinese lenders as much as $3.5 trillion, much of it in USD which are more expensive to acquire than they used to be. This is why a trade war is so threatening to China. Revenue from exports to the US helps pay that debt.

So that’s one problem, but the internal debt is not exactly benign. Yes, a state-dominated economy like China’s can deal with debt in its own currency. It has many ways to extend and pretend. But they have limits and don’t work forever. It has to be worked off.

Job Jitters

Leverage is fun. It lets you do things you otherwise couldn’t. Deleveraging is the opposite of fun because you must do things you would rather avoid. This is a particular problem for the Chinese government, which must keep a large population fed, housed, and otherwise content. Thus the drive to improve the conditions or move 150 million people from the poverty of rural China to the cities.

Beijing has many tricks up its sleeve but China’s labor market has its own dynamic.

From my friends at Gavekal Dragonomics, written by Ernan Cui:

China’s job market is proving to be an early casualty of the US-China trade conflict. Layoffs in manufacturing accelerated over the second half of 2018 as US tariffs fell into place, and job losses have now matched the pace seen during the economic slowdown of 2015-6. But the situation is arguably worse this time, as the service-sector employers that previously absorbed many laid-off workers are now being squeezed by tighter regulations. Government officials are trying to adjust and soften policies to help employment, but the outlook for household income and consumer spending in China in 2019 is clearly worsening.

Consumer spending had already slowed in 2018, but most of the deterioration came from a decline in auto sales. [Which still total 27 million cars sold.] That was largely the result of the end of several years of favorable policies that had front-loaded vehicle purchases; spending on services and other consumer goods actually held up fairly well. But China looks to be headed for a more broad-based slowdown in consumer spending in at least the first half of 2019. The employment components of the PMI surveys, both for manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors, started to deteriorate sharply in September. These are decent leading indicators of household income growth (see chart), so a further slowdown in income and consumption in the next couple of quarters is almost guaranteed.

Now, we should note that Chinese economic data is questionable in the best of circumstances. The last thing Beijing wants is to give the public rigorous data proving how hopeless its job-hunting is, or how unlikely its income is to grow. Fortunately, we have alternative sources like Gavekal, China Beige Book, and others with on-the-ground presence and access to non-government data.

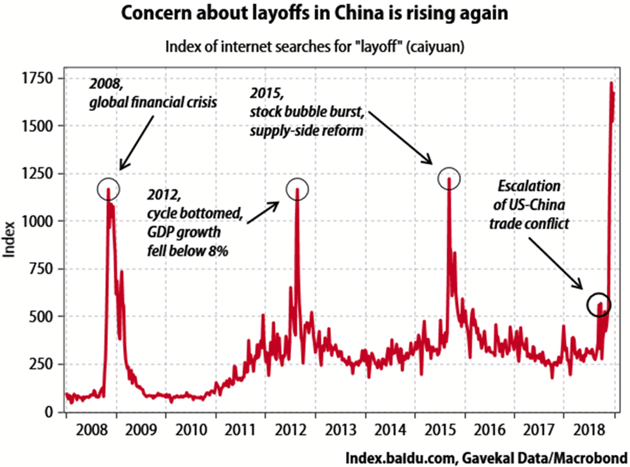

Gavekal in their broad-based research found an amazing data point, too. The graph below shows an index of Chinese internet searches for the word “layoff.” Notice where it is now compared to 2008 and other recent economic slowdowns.

Now, this doesn’t mean Chinese employers are actually conducting layoffs. It means people are looking for information on the topic, and I think it’s fair to call that a sign of worry. What is causing this concern? Do Chinese workers see something that bullish Western analysts are missing?

Credit Intensity

Economic weakness is relative. Like anything else, coming down from a level to which you are accustomed is hard, even if you land in a place that isn’t so bad in absolute terms.

Assuming (for discussion’s sake) the official numbers are right, China’s GDP growth has been around 4% at worst going all the way back to the 1980s, and usually much higher. The US has struggled to achieve anything near that. So a decline from the 6.9% growth seen in 2017 to, say, 6%, is a big deal to the Chinese. And that’s what the government apparently expects. Reuters reported on January 11 that in March the government will announce a 2019 growth target goal in the 6-6.5% range… and China always hits the target. Funny how that works.

Here in the US we would celebrate 4% growth. (I think by the end of 2019 we may be wishing for even 2% growth.) In China, they will hit the proverbial panic button at anything south of 6%. Look for the government to respond with even more debt and infrastructure spending to try and stimulate the economy and maintain growth in the 6% range.

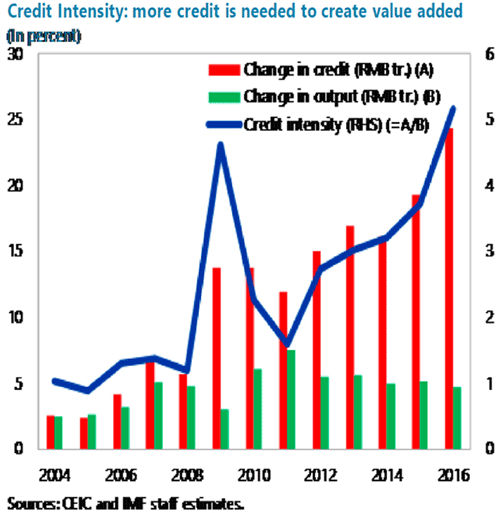

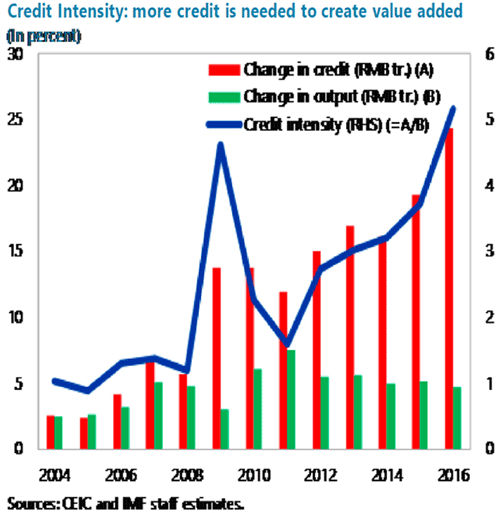

The problem is, like a medicine to which the body adapts, debt is no longer having the same kind of effect. An IMF study last year measured China’s “credit intensity” over time.

Source: IMF

I’m sorry that picture is fuzzy—it’s that way in the original, too. Here is how they explain it. I bolded the important part.

However, over the last five years, domestic nominal credit to the nonfinancial sector has more than doubled, and the domestic nonfinancial sector credit-to-GDP ratio rose to about 235 percent of GDP as of end-2016. 2 During this period, the efficiency of credit expansion has increasingly deteriorated, pointing to growing resource misallocation. In 2007-08, about RMB 6½ trillion of new credit was needed to raise nominal GDP by about RMB 5 trillion per year. In 2015-16, it took more than RMB 20 trillion in new credit for the same nominal GDP growth.

So in less than a decade, the amount of debt needed to produce a given impact on GDP more than tripled. I’ve cited data from Lacy Hunt showing a similar trend in the US but it’s nowhere near that magnitude.

That tells us something important: In the next downturn, slowdown, or whatever you call it, Beijing may not be able to borrow its way out of the hole. Or if it does, the amounts could be astronomically high.

But absent debt stimulus, what else can they do? As noted, Xi Jinping has many tools. Some are more pleasant than others. I seriously doubt he has any way to restore growth to what everyone wants without massive adjustments (i.e., more debt). And it will be painful not just for Chinese, but Americans, too.

Read Full Story »»»

• DiscoverGold

Click on "In reply to", for Authors past commentaries

By: John Mauldin | January 18, 2019

Demand Pulled Forward

The 2008 financial crisis and recession hit China hard, as it did everyone else. Not every country responded like China did, though. Most couldn’t do what China did because they lacked either the financial resources or the political ability. China had both, and so launched a stimulus program of mind-boggling proportions. Beijing compelled local governments and state-owned enterprises to take on massive debt for giant infrastructure projects, huge capacity expansions, and pretty much anything else they could imagine that would put people to work and bolster public confidence. Yes, they built ghost cities.

(Incidentally, the classic ghost city was in Mongolia, literally vacant for a time but now well on its way to being fully occupied or bought. Long game and deep pockets, indeed.)

Not coincidentally, China has doubled its debt relative to GDP since the beginning of the century, and the bulk of that was after 2009.

But it’s how they grew that debt I find amazing. We must remember that the Chinese economy is managed from the top down. The Chinese government is very aware of how its shadow banking system operates. Half of the total debt is from the nonfinancial (i.e., shadow banks) sector. And while Simon Hunt talks about deleveraging, when I talked with him what he really means is that the Chinese government is trying to move from Wild West shadow banking to more traditional bank financing. Central bankers sometimes accompany private bankers to meet loan-seeking businesses. Chinese characteristics, indeed.

In my research for this letter I came across several mentions that China is planning to move another 150 million rural citizens to urban areas, many into so-called second-tier cities. Only in China can a second-tier city have five million people. And people moving from the country into the city becomes far more productive in terms of GDP. And China is beginning to focus on upgrading the infrastructure and the rural cities as well.

As the entire world will come to realize in the middle of the next decade, the debt which financed that infrastructure does have a carrying cost. Even in a top-down economy. Yes, much of it is internal but our first concern is China’s enormous amount of dollar-denominated debt. Here’s Christopher Balding with the numbers:

According to official data, short-term debt accounted for 62 percent of the total [of almost $2 trillion in debt] as of September, meaning that $1.2 trillion will have to be rolled over this year. Just as worrying is the speed of increase: Total external debt has increased 14 percent in the past year and 35 percent since the beginning of 2017.

External debt is no longer a trivial slice of China’s foreign-exchange reserves, which stood at just over $3 trillion at the end of November, little changed from two years earlier. Short-term foreign debt increased to 39 percent of reserves in September, from 26 percent in March 2016.

The true picture may be more precarious. China’s external debt was estimated between $3 trillion and $3.5 trillion by Daiwa Capital Markets in an August report. In other words, total foreign liabilities could be understated by as much as $1.5 trillion after accounting for borrowing in financial centres such as Hong Kong, New York, and the Caribbean islands that isn’t included in the official tally.

So, China could owe non-Chinese lenders as much as $3.5 trillion, much of it in USD which are more expensive to acquire than they used to be. This is why a trade war is so threatening to China. Revenue from exports to the US helps pay that debt.

So that’s one problem, but the internal debt is not exactly benign. Yes, a state-dominated economy like China’s can deal with debt in its own currency. It has many ways to extend and pretend. But they have limits and don’t work forever. It has to be worked off.

Job Jitters

Leverage is fun. It lets you do things you otherwise couldn’t. Deleveraging is the opposite of fun because you must do things you would rather avoid. This is a particular problem for the Chinese government, which must keep a large population fed, housed, and otherwise content. Thus the drive to improve the conditions or move 150 million people from the poverty of rural China to the cities.

Beijing has many tricks up its sleeve but China’s labor market has its own dynamic.

From my friends at Gavekal Dragonomics, written by Ernan Cui:

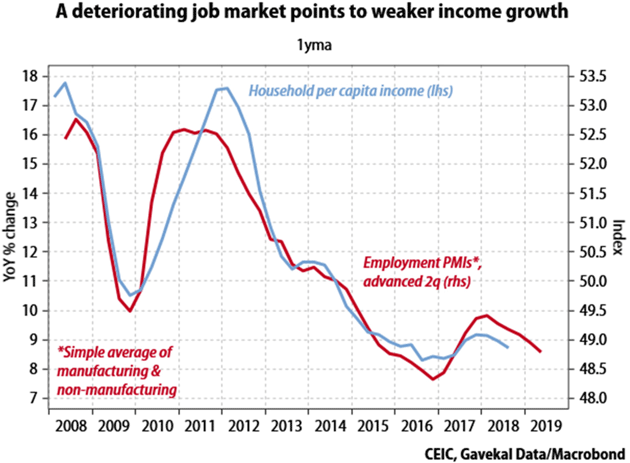

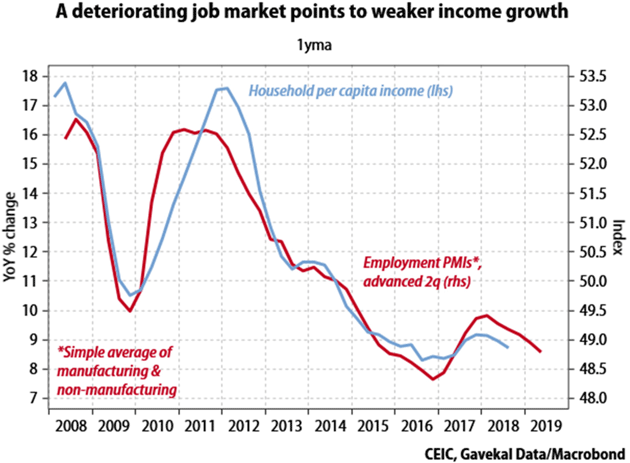

China’s job market is proving to be an early casualty of the US-China trade conflict. Layoffs in manufacturing accelerated over the second half of 2018 as US tariffs fell into place, and job losses have now matched the pace seen during the economic slowdown of 2015-6. But the situation is arguably worse this time, as the service-sector employers that previously absorbed many laid-off workers are now being squeezed by tighter regulations. Government officials are trying to adjust and soften policies to help employment, but the outlook for household income and consumer spending in China in 2019 is clearly worsening.

Consumer spending had already slowed in 2018, but most of the deterioration came from a decline in auto sales. [Which still total 27 million cars sold.] That was largely the result of the end of several years of favorable policies that had front-loaded vehicle purchases; spending on services and other consumer goods actually held up fairly well. But China looks to be headed for a more broad-based slowdown in consumer spending in at least the first half of 2019. The employment components of the PMI surveys, both for manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors, started to deteriorate sharply in September. These are decent leading indicators of household income growth (see chart), so a further slowdown in income and consumption in the next couple of quarters is almost guaranteed.

Now, we should note that Chinese economic data is questionable in the best of circumstances. The last thing Beijing wants is to give the public rigorous data proving how hopeless its job-hunting is, or how unlikely its income is to grow. Fortunately, we have alternative sources like Gavekal, China Beige Book, and others with on-the-ground presence and access to non-government data.

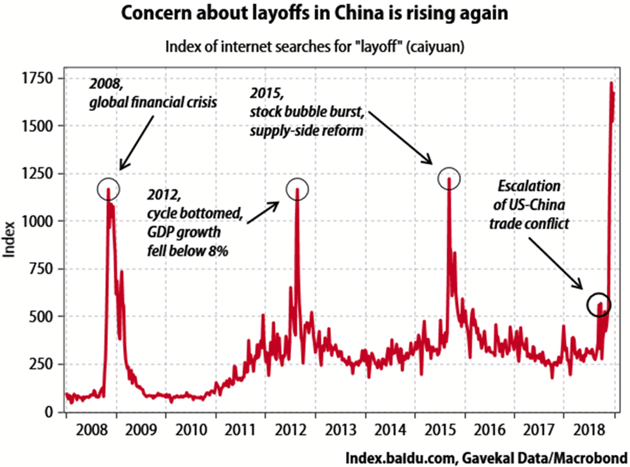

Gavekal in their broad-based research found an amazing data point, too. The graph below shows an index of Chinese internet searches for the word “layoff.” Notice where it is now compared to 2008 and other recent economic slowdowns.

Now, this doesn’t mean Chinese employers are actually conducting layoffs. It means people are looking for information on the topic, and I think it’s fair to call that a sign of worry. What is causing this concern? Do Chinese workers see something that bullish Western analysts are missing?

Credit Intensity

Economic weakness is relative. Like anything else, coming down from a level to which you are accustomed is hard, even if you land in a place that isn’t so bad in absolute terms.

Assuming (for discussion’s sake) the official numbers are right, China’s GDP growth has been around 4% at worst going all the way back to the 1980s, and usually much higher. The US has struggled to achieve anything near that. So a decline from the 6.9% growth seen in 2017 to, say, 6%, is a big deal to the Chinese. And that’s what the government apparently expects. Reuters reported on January 11 that in March the government will announce a 2019 growth target goal in the 6-6.5% range… and China always hits the target. Funny how that works.

Here in the US we would celebrate 4% growth. (I think by the end of 2019 we may be wishing for even 2% growth.) In China, they will hit the proverbial panic button at anything south of 6%. Look for the government to respond with even more debt and infrastructure spending to try and stimulate the economy and maintain growth in the 6% range.

The problem is, like a medicine to which the body adapts, debt is no longer having the same kind of effect. An IMF study last year measured China’s “credit intensity” over time.

Source: IMF

I’m sorry that picture is fuzzy—it’s that way in the original, too. Here is how they explain it. I bolded the important part.

However, over the last five years, domestic nominal credit to the nonfinancial sector has more than doubled, and the domestic nonfinancial sector credit-to-GDP ratio rose to about 235 percent of GDP as of end-2016. 2 During this period, the efficiency of credit expansion has increasingly deteriorated, pointing to growing resource misallocation. In 2007-08, about RMB 6½ trillion of new credit was needed to raise nominal GDP by about RMB 5 trillion per year. In 2015-16, it took more than RMB 20 trillion in new credit for the same nominal GDP growth.

So in less than a decade, the amount of debt needed to produce a given impact on GDP more than tripled. I’ve cited data from Lacy Hunt showing a similar trend in the US but it’s nowhere near that magnitude.

That tells us something important: In the next downturn, slowdown, or whatever you call it, Beijing may not be able to borrow its way out of the hole. Or if it does, the amounts could be astronomically high.

But absent debt stimulus, what else can they do? As noted, Xi Jinping has many tools. Some are more pleasant than others. I seriously doubt he has any way to restore growth to what everyone wants without massive adjustments (i.e., more debt). And it will be painful not just for Chinese, but Americans, too.

Read Full Story »»»

• DiscoverGold

Click on "In reply to", for Authors past commentaries

Information posted to this board is not meant to suggest any specific action, but to point out the technical signs that can help our readers make their own specific decisions. Your Due Dilegence is a must!

• DiscoverGold

Join the InvestorsHub Community

Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.