| Followers | 686 |

| Posts | 142517 |

| Boards Moderated | 35 |

| Alias Born | 03/10/2004 |

Saturday, May 12, 2018 9:18:31 AM

Credit-Driven Train Crash, Part 1

By: John Mauldin | May 11, 2018

THOUGHTS FROM THE FRONTLINE

In last week’s letter, I mentioned an insightful comment my friend Peter Boockvar made at dinner in New York: “We now have credit cycles instead of economic cycles.” That one sentence provoked numerous phone calls and emails, all seeking elaboration. What did Peter mean by that statement?

I vividly remembered that quote because it resonated with me. I’ve been saying for some time that the next financial crisis will bring a major debt crisis. But as you’ll see today, it is a small part, maybe the opening event, of a rapidly-approaching train wreck. We’ll need several weeks to tease out all the causes and consequences, so this letter will be the first in a series. These will be some of the most important letters I’ve ever written. Something is on the tracks ahead and I don’t see how we’ll avoid hitting it. So, read these next few letters carefully.

Cycling Economies

In 1999, I began saying the tech bubble would eventually spark a recession. Timing was unclear because stock bubbles can blow way bigger than we can imagine. Then the yield curve inverted, and I said recession was certain. I was early in that call, but it happened.

In late 2006, I began highlighting the subprime crisis, and subsequently the yield curve again inverted, necessitating another recession call. Again, I was early, but you see the pattern.

Now let’s fast-forward to today. Here’s what I said last week that drew so much interest.

Peter [Boockvar] made an extraordinarily cogent comment that I’m going to use from now on: “We no longer have business cycles, we have credit cycles.”

For those who don’t know Peter, he is the CIO of Bleakley Advisory Group and editor of the excellent Boock Report. Let’s cut that small but meaty sound bite into pieces.

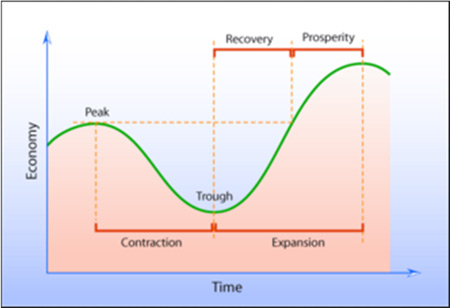

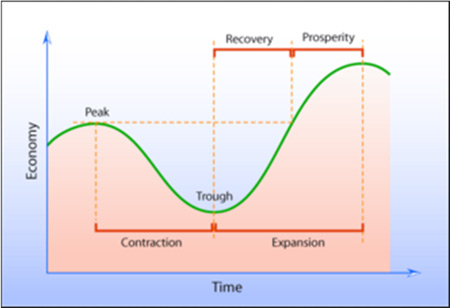

What do we mean by “business cycle,” exactly? Well, it looks something like this:

A growing economy peaks, contracts to a trough (what we call “recession”), recovers to enter prosperity, and hits a higher peak. Then the process repeats. The economy is always in either expansion or contraction.

Economists disagree on the details of all this. Wikipedia has a good overview of the various perspectives, if you want to geek out. The high-level question is why economies must cycle at all. Why can’t we have steady growth all the time? Answers vary. Whatever it is, periodically something derails growth and something else restarts it.

This pattern broke down in the last decade. We had an especially painful contraction followed by an extraordinarily weak expansion. GDP growth should reach 5% in the recovery and prosperity phases, not the 2% we have seen. Peter blames the Federal Reserve’s artificially low interest rates. Here’s how he put it in an April 18 letter to his subscribers.

To me, it is a very simple message being sent. We must understand that we no longer have economic cycles. We have credit cycles that ebb and flow with monetary policy. After all, when the Fed cuts rates to extremes, its only function is to encourage the rest of us to borrow a lot of money and we seem to have been very good at that. Thus, in reverse, when rates are being raised, when liquidity rolls away, it discourages us from taking on more debt. We don’t save enough.

This goes back farther than 2008. The Greenspan Fed pushed rates abnormally low in the late 1990s even though the then-booming economy needed no stimulus. That was in part to provide liquidity to a Y2K-wary public and partly in response to the 1998 market turmoil, but they were slow to withdraw the extra cash. Bernanke was again generous to borrowers in the 2000s, contributing to the housing crisis and Great Recession. We’re now 20 years into training people (and businesses) that running up debt is fun and easy… and they’ve responded.

But over time, debt stops stimulating growth. Over this series, we will see that it takes more debt accumulation for every point of GDP growth, both in the US and elsewhere. Hence, the flat-to-mild “recovery” years. I’ve cited academic literature via my friend Lacy Hunt that debt eventually becomes a drag on growth.

Debt-fueled growth is fun at first but simply pulls forward future spending, which we then miss. Now we’re entering the much more dangerous reversal phase in which the Fed tries to break the debt addiction. We all know that never ends well.

So, Peter’s point is that a Fed-driven credit cycle now supersedes the traditional business cycle. Since debt drives so much GDP growth, its cost (i.e. interest rates) is the main variable defining where we are in the cycle. The Fed controls that cost—or at least tries to—so we all obsess on Fed policy. And rightly so.

Among other effects, debt boosts asset prices. That’s why stocks and real estate have performed so well. But with rates now rising and the Fed unloading assets, those same prices are highly vulnerable. An asset’s value is what someone will pay for it. If financing costs rise and buyers lack cash, the asset price must fall. And fall it will. The consensus at my New York dinner was recession in the last half of 2019. Peter expects it sooner, in Q1 2019.

If that’s right, financial market fireworks aren’t far away.

Corporate Debt Disaster

In an old-style economic cycle, recessions triggered bear markets. Economic contraction slowed consumer spending, corporate earnings fell, and stock prices dropped. That’s not how it works when the credit cycle is in control. Lower asset prices aren’t the result of a recession. They cause the recession. That’s because access to credit drives consumer spending and business investment. Take it away and they decline. Recession follows.

If some of this sounds like the Hyman Minsky financial instability hypothesis I’ve described before, you’re exactly right. Minsky said exuberant firms take on too much debt, which paralyzes them, and then bad things start happening. I think we’re approaching that point.

The last “Minsky Moment” came from subprime mortgages and associated derivatives. Those are getting problematic again, but I think today’s bigger risk is the sheer amount of corporate debt, especially high-yield bonds that will be very hard to liquidate in a crisis.

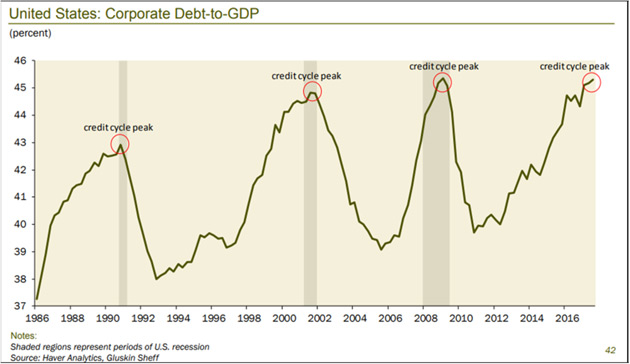

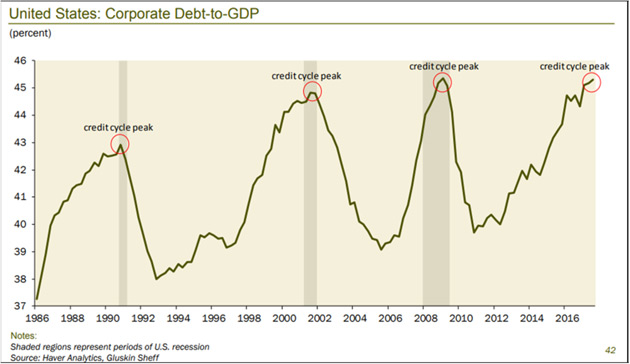

Corporate debt is now at a level that has not ended well in past cycles. Here’s a chart from Dave Rosenberg:

The Debt/GDP ratio could go higher still, but I think not much more. Whenever it falls, lenders (including bond fund and ETF investors) will want to sell. Then comes the hard part: to whom?

You see, it’s not just borrowers who’ve become accustomed to easy credit. Many lenders assume they can exit at a moment’s notice. One reason for the Great Recession was so many borrowers had sold short-term commercial paper to buy long-term assets. Things got worse when they couldn’t roll over the debt and some are now doing exactly the same thing again, except in much riskier high-yield debt. We have two related problems here.

• Corporate debt and especially high-yield debt issuance has exploded since 2009.

• Tighter regulations discouraged banks from making markets in corporate and HY debt.

Both are problems but the second is worse. Experts tell me that Dodd-Frank requirements have reduced major bank market-making abilities by around 90%. For now, bond market liquidity is fine because hedge funds and other non-bank lenders have filled the gap. The problem is they are not true market makers. Nothing requires them to hold inventory or buy when you want to sell. That means all the bids can “magically” disappear just when you need them most. These “shadow banks” are not in the business of protecting your assets. They are worried about their own profits and those of their clients.

Gavekal’s Louis Gave wrote a fascinating article on this last week titled, “The Illusion of Liquidity and Its Consequences.” He pulled the numbers on corporate bond ETFs and compared it to the inventory trading desks were holding—a rough measure of liquidity.

(Incidentally, you’ll get that full report on Monday if you subscribe to Over My Shoulder. What you learn could easily pay for your first year.)

* * *

http://www.mauldineconomics.com/frontlinethoughts/credit-driven-train-crash-part-1

• DiscoverGold

Click on "In reply to", for Authors past commentaries

By: John Mauldin | May 11, 2018

THOUGHTS FROM THE FRONTLINE

In last week’s letter, I mentioned an insightful comment my friend Peter Boockvar made at dinner in New York: “We now have credit cycles instead of economic cycles.” That one sentence provoked numerous phone calls and emails, all seeking elaboration. What did Peter mean by that statement?

I vividly remembered that quote because it resonated with me. I’ve been saying for some time that the next financial crisis will bring a major debt crisis. But as you’ll see today, it is a small part, maybe the opening event, of a rapidly-approaching train wreck. We’ll need several weeks to tease out all the causes and consequences, so this letter will be the first in a series. These will be some of the most important letters I’ve ever written. Something is on the tracks ahead and I don’t see how we’ll avoid hitting it. So, read these next few letters carefully.

Cycling Economies

In 1999, I began saying the tech bubble would eventually spark a recession. Timing was unclear because stock bubbles can blow way bigger than we can imagine. Then the yield curve inverted, and I said recession was certain. I was early in that call, but it happened.

In late 2006, I began highlighting the subprime crisis, and subsequently the yield curve again inverted, necessitating another recession call. Again, I was early, but you see the pattern.

Now let’s fast-forward to today. Here’s what I said last week that drew so much interest.

Peter [Boockvar] made an extraordinarily cogent comment that I’m going to use from now on: “We no longer have business cycles, we have credit cycles.”

For those who don’t know Peter, he is the CIO of Bleakley Advisory Group and editor of the excellent Boock Report. Let’s cut that small but meaty sound bite into pieces.

What do we mean by “business cycle,” exactly? Well, it looks something like this:

A growing economy peaks, contracts to a trough (what we call “recession”), recovers to enter prosperity, and hits a higher peak. Then the process repeats. The economy is always in either expansion or contraction.

Economists disagree on the details of all this. Wikipedia has a good overview of the various perspectives, if you want to geek out. The high-level question is why economies must cycle at all. Why can’t we have steady growth all the time? Answers vary. Whatever it is, periodically something derails growth and something else restarts it.

This pattern broke down in the last decade. We had an especially painful contraction followed by an extraordinarily weak expansion. GDP growth should reach 5% in the recovery and prosperity phases, not the 2% we have seen. Peter blames the Federal Reserve’s artificially low interest rates. Here’s how he put it in an April 18 letter to his subscribers.

To me, it is a very simple message being sent. We must understand that we no longer have economic cycles. We have credit cycles that ebb and flow with monetary policy. After all, when the Fed cuts rates to extremes, its only function is to encourage the rest of us to borrow a lot of money and we seem to have been very good at that. Thus, in reverse, when rates are being raised, when liquidity rolls away, it discourages us from taking on more debt. We don’t save enough.

This goes back farther than 2008. The Greenspan Fed pushed rates abnormally low in the late 1990s even though the then-booming economy needed no stimulus. That was in part to provide liquidity to a Y2K-wary public and partly in response to the 1998 market turmoil, but they were slow to withdraw the extra cash. Bernanke was again generous to borrowers in the 2000s, contributing to the housing crisis and Great Recession. We’re now 20 years into training people (and businesses) that running up debt is fun and easy… and they’ve responded.

But over time, debt stops stimulating growth. Over this series, we will see that it takes more debt accumulation for every point of GDP growth, both in the US and elsewhere. Hence, the flat-to-mild “recovery” years. I’ve cited academic literature via my friend Lacy Hunt that debt eventually becomes a drag on growth.

Debt-fueled growth is fun at first but simply pulls forward future spending, which we then miss. Now we’re entering the much more dangerous reversal phase in which the Fed tries to break the debt addiction. We all know that never ends well.

So, Peter’s point is that a Fed-driven credit cycle now supersedes the traditional business cycle. Since debt drives so much GDP growth, its cost (i.e. interest rates) is the main variable defining where we are in the cycle. The Fed controls that cost—or at least tries to—so we all obsess on Fed policy. And rightly so.

Among other effects, debt boosts asset prices. That’s why stocks and real estate have performed so well. But with rates now rising and the Fed unloading assets, those same prices are highly vulnerable. An asset’s value is what someone will pay for it. If financing costs rise and buyers lack cash, the asset price must fall. And fall it will. The consensus at my New York dinner was recession in the last half of 2019. Peter expects it sooner, in Q1 2019.

If that’s right, financial market fireworks aren’t far away.

Corporate Debt Disaster

In an old-style economic cycle, recessions triggered bear markets. Economic contraction slowed consumer spending, corporate earnings fell, and stock prices dropped. That’s not how it works when the credit cycle is in control. Lower asset prices aren’t the result of a recession. They cause the recession. That’s because access to credit drives consumer spending and business investment. Take it away and they decline. Recession follows.

If some of this sounds like the Hyman Minsky financial instability hypothesis I’ve described before, you’re exactly right. Minsky said exuberant firms take on too much debt, which paralyzes them, and then bad things start happening. I think we’re approaching that point.

The last “Minsky Moment” came from subprime mortgages and associated derivatives. Those are getting problematic again, but I think today’s bigger risk is the sheer amount of corporate debt, especially high-yield bonds that will be very hard to liquidate in a crisis.

Corporate debt is now at a level that has not ended well in past cycles. Here’s a chart from Dave Rosenberg:

The Debt/GDP ratio could go higher still, but I think not much more. Whenever it falls, lenders (including bond fund and ETF investors) will want to sell. Then comes the hard part: to whom?

You see, it’s not just borrowers who’ve become accustomed to easy credit. Many lenders assume they can exit at a moment’s notice. One reason for the Great Recession was so many borrowers had sold short-term commercial paper to buy long-term assets. Things got worse when they couldn’t roll over the debt and some are now doing exactly the same thing again, except in much riskier high-yield debt. We have two related problems here.

• Corporate debt and especially high-yield debt issuance has exploded since 2009.

• Tighter regulations discouraged banks from making markets in corporate and HY debt.

Both are problems but the second is worse. Experts tell me that Dodd-Frank requirements have reduced major bank market-making abilities by around 90%. For now, bond market liquidity is fine because hedge funds and other non-bank lenders have filled the gap. The problem is they are not true market makers. Nothing requires them to hold inventory or buy when you want to sell. That means all the bids can “magically” disappear just when you need them most. These “shadow banks” are not in the business of protecting your assets. They are worried about their own profits and those of their clients.

Gavekal’s Louis Gave wrote a fascinating article on this last week titled, “The Illusion of Liquidity and Its Consequences.” He pulled the numbers on corporate bond ETFs and compared it to the inventory trading desks were holding—a rough measure of liquidity.

(Incidentally, you’ll get that full report on Monday if you subscribe to Over My Shoulder. What you learn could easily pay for your first year.)

* * *

http://www.mauldineconomics.com/frontlinethoughts/credit-driven-train-crash-part-1

• DiscoverGold

Click on "In reply to", for Authors past commentaries

Information posted to this board is not meant to suggest any specific action, but to point out the technical signs that can help our readers make their own specific decisions. Your Due Dilegence is a must!

• DiscoverGold

Join the InvestorsHub Community

Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.