Wednesday, April 18, 2018 7:13:03 PM

Originalism: Neil Gorsuch's constitutional philosophy explained

"Trump Loses SCOTUS Immigration Case Because Of Gorsuch"

Donald Trump’s supreme court nominee aims to interpret the constitution

according to its original intent – and that could lead to problems for the president

Ed Pilkington in New York

@edpilkington

Thu 2 Feb 2017 22.00 AEDT

Last modified on Sat 10 Feb 2018 05.51 AEDT

Judge Neil Gorsuch has promised to be a ‘faithful servant’ of the constitution.

Photograph: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

At his unveiling on Tuesday night as Donald Trump’s choice to fill the US supreme court .. https://www.theguardian.com/law/us-supreme-court .. vacancy, Neil Gorsuch paid homage not to the man standing beside him, who had just nominated him to one of the most powerful judicial positions in the country, but to a document written 230 years ago.

Gorsuch, a federal appellate judge based in Denver, promised that should he get through the confirmation process he would act as a “faithful servant” to what he called “the greatest charter of human liberty the world has ever known”. He was referring to the US constitution, the supreme law of the land drafted in 1787.

He was not being rhetorical. Gorsuch describes himself as an “originalist”, indicating that he places overwhelming importance on the original meaning of the constitution as it was understood by “we the people” at the time it was written.

That puts him in a very select group of judges – maybe no more than 30 – who identify themselves as “originalists”. What unites them is that they put as much emphasis on the original understanding of the US constitution as Christian fundamentalists say they put on the original wording of the Bible.

Until his death last year, one of the most prominent members of the group was Antonin Scalia, the supreme court justice whom Gorsuch is now lined up to replace. Scalia helped spread the word of originalism among conservative judges in the 1980s as a way of pushing back on what he considered to be the increasingly outlandish opinions of his progressive peers.

Judges were there, Scalia argued, not to make up their own laws or politically motivated judgments, but to cleave faithfully to the meaning of the framers’ writings as they were understood back in the 18th century by the American people.

“Originalists ask what the constitution meant at the time it was written, and then argue that the meaning is fixed – it doesn’t change because the world has changed and we now have new problems to deal with,” said Lawrence Solum, a professor at Georgetown Law who is a leading theorist of constitutional originalism.

David Feder, a Los Angeles-based lawyer, had first-hand experience of what that meant to Gorsuch in practice when he worked as his law clerk on the federal 10th circuit court of appeals. “Whenever a constitutional issue came up in our cases, [Gorsuch] sent one of his clerks on a deep dive through the historical sources. ‘We need to get this right,’ was the motto – and right meant ‘as originally understood’,” Feder recalled .. http://yalejreg.com/nc/the-administrative-law-originalism-of-neil-gorsuch/ .. recently in the Yale Journal of Regulation.

Even taking into account the modernizing influence of the amendments that have been made to the constitution – most recently .. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twenty-seventh_Amendment_to_the_United_States_Constitution .. a prohibition on changes to congresspeople’s salaries taking effect until the start of the next term for representatives, passed in 1992 – a strict adherence to the founding documents can prove tricky. In 1787, most transportation was by ship or horse, not by plane or motorcar; communication was on parchment and paper rather than through the internet and cellphones; gay marriage was beyond most people’s imagination.

Conundrums can arrive at the level of the word. Solum points out that the seventh amendment, adopted as part of the bill of rights in 1791, guarantees the right to a jury trial in civil cases where the amount in dispute rises above “twenty dollars”.

Trouble is, the word “dollar” actually referred to a Spanish silver coin that was the main form of currency in 1791. Similarly, the reference to “domestic violence” in article four of the constitution does not equate to spousal or child abuse as it would today but to riots or insurrections within the boundaries of a single state.

The world has changed in ways that two-centuries old documents cannot reach. “We have a freedom of speech provision, but when it was written, no one spoke over the internet,” Solum said.

Originalists grapple with these contradictions in different ways. In the case of Gorsuch, his approach appears to be to try to stick rigidly to the spirit of the original meaning of the constitution while adapting it to modern circumstances.

Advertisement

That makes him something of an unknown quantity: it is hard to predict how he would respond to crucial areas of jurisprudence. Take gay marriage, for example: in the unlikely even that it were to come before the supreme court again, would Gorsuch follow the line taken by Scalia, that gay marriage was not covered by the 14th amendment’s “privileges and immunities” clause because at the time the amendment was adopted in 1868, same-sex marriage was illegal?

Or would Gorsuch take the view that the original definition of who was entitled to the privilege of marriage could change as society changes? “The people who wrote the provision did not fully envision where it would take us,” Solum said. “Gorsuch could be in that camp: that the meaning of the words remains the same but the implications change as social norms change.”

There is no easy way to answer that question, as Gorsuch has participated in no same-sex marriage case law that would provide clues.

If confirmed, though, Gorsuch could prove to be an unreliable ally from Trump’s point of view, at least on occasion. Certainly, his accent on sticking to the meaning of the past brings him generally in line with the rightwing conservatism of the Republican party.

But originalists like Gorsuch see themselves as fierce protectors of the checks and balances that lie at the core of the US constitution. And as such they have the potential to bristle at presidents seen to be overstepping the limits of their executive powers.

“It is certainly possible that Donald Trump .. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/donaldtrump .. will try and do things that go well beyond the original understanding of executive power,” Solum said. “When that happens, the president should be ready to be surprised by his nominee’s response.”

Topics

https://www.theguardian.com/law/2017/feb/02/originalism-constitution-supreme-court-neil-gorsuch

Gorsuch's position in that SCOTUS immigration case suggests this article may not be far off the mark.

Despite Gorsuch, Supreme Court Remains Centrist

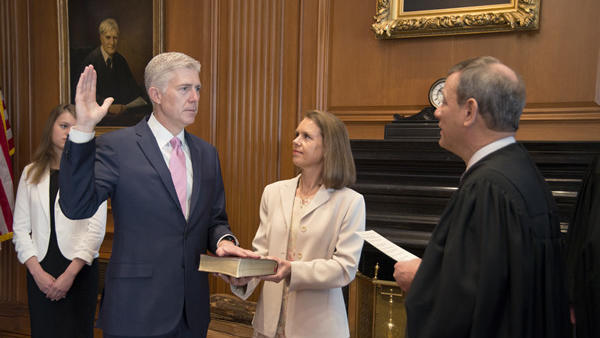

Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. administered the Constitutional Oath to Justice

Neil M. Gorsuch as his wife Marie Louise Gorsuch held the Bible at the Supreme

Court Building April 10. (Handout /)

NOAH FELDMAN

April 11 2017

With the swearing-in Monday of Justice Neil Gorsuch, the U.S. Supreme Court's configuration shifts to a 4-4 balance with a single centrist justice as the swing vote. If that sounds familiar, it should. It's been the normal state of affairs since 1986, when Justice Antonin Scalia joined, and on some issues all the way back to Richard Nixon's administration.

This time, of course, the configuration results from the Republican Senate's unprecedented and successful gamble to block President Barack Obama from filling Scalia's seat. His pick, Judge Merrick Garland .. http://www.courant.com/topic/crime-law-justice/justice-system/merrick-garland-PEGPF00168-topic.html , would have given the liberals a clear, consistent majority for the first time since the days of Chief Justice Earl Warren — unless and until President Donald Trump had the chance to replace one of the court's liberals.

It's nevertheless worth exploring the fascinating phenomenon of the enduring centrist court, and asking the question: Is it an accident? Or is it a feature of the Supreme Court in its current condition, when liberal and conservative justices are all activists?

The court's composition follows from a feature of constitutional design that includes some luck, namely that justices can serve for life and that the president who's in office gets to nominate the replacement (or used to). If the presidency changes parties with some regularity, and justices retire or die on an arbitrary schedule, that should ensure some balance.

The first condition has been fulfilled since the death of Franklin Roosevelt, who was elected four times and picked an astonishing nine justices if you include a chief who was already on the court. If you start with Harry Truman, the longest run of one party in the presidency has been 12 years, for two terms of Ronald Reagan and one for George H.W. Bush. Otherwise, the presidency has typically flipped parties every eight years, with Jimmy Carter's single term leading to the only shorter flip.

The second condition hasn't been fulfilled perfectly, because some justices retire when they like the president who will replace them. But there has been surprisingly little of that strategic choice by the justices, despite the politicization of the process. Chief Justice William Rehnquist died in office, as did Scalia. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor retired because of her husband's failing health.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg stayed on the court past Barack Obama's presidency despite being well into her 80s and having survived not one but two bouts with cancer. If that's not a rejection of the strategic approach, I don't know what is.

But beyond constitutional structure, there's another extraordinary, non-accidental fact about the centrist court: It's been maintained in large part by individual justices' drift to the center.

The most salient example is Justice Anthony Kennedy. He's the swing vote today, as he has been since O'Connor retired a decade ago. But for nearly 20 years before that, Kennedy wasn't perceived as the swing voter — O'Connor was. Kennedy was considered a reliable conservative, with a few outlying liberal opinions on equality for gay people and the abortion compromise in Casey v. Planned Parenthood.

It's not that Kennedy just seemed more liberal when O'Connor retired. He actually became more liberal. His liberal opinions in recent years on abortion and affirmative action prove this definitively. Each represented a real shift leftward from his earlier opinions on the same subject.

Kennedy's shift had internal theoretical motivations, no doubt, grounded in the development of his jurisprudence of equal dignity. But it also resulted from the natural impulse to influence and the power that comes from being the swing vote.

The court's way of setting precedent gives enormous power to the swing voter. If there's no majority opinion, the narrowest opinion for the result that gets five votes becomes controlling precedent.

Even if the swing voter joins the majority opinion and writes a separate concurrence, his or her narrow opinion has a way of becoming the majority opinion in future cases, as the other justices try to win the votes of the swing justice.

The upshot is that the center-most justice, measured by ideology, will always have an incentive to tack toward the middle under the existing system. For the moment, that is still Kennedy.

But when Kennedy is no longer in the center, some other justice may emerge to take center stage, literally.

I'm not guaranteeing a centrist court forever. But if Justices Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer can hold out until a Democratic president is elected, or if a Democratic Senate denies Trump any appointments until a Democrat replaces him, we may see the centrist Supreme Court remaining into the distant future.

Maybe the American people want it that way.

Noah Feldman, a professor of constitutional and international law at Harvard University and former clerk

to U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Souteris, writes for Bloomberg View, where this first appeared.

http://www.courant.com/opinion/op-ed/hc-op-feldman-neil-gorsuch-supreme-court-balance-0411-20170410-story.html

"Trump Loses SCOTUS Immigration Case Because Of Gorsuch"

Donald Trump’s supreme court nominee aims to interpret the constitution

according to its original intent – and that could lead to problems for the president

Ed Pilkington in New York

@edpilkington

Thu 2 Feb 2017 22.00 AEDT

Last modified on Sat 10 Feb 2018 05.51 AEDT

Judge Neil Gorsuch has promised to be a ‘faithful servant’ of the constitution.

Photograph: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

At his unveiling on Tuesday night as Donald Trump’s choice to fill the US supreme court .. https://www.theguardian.com/law/us-supreme-court .. vacancy, Neil Gorsuch paid homage not to the man standing beside him, who had just nominated him to one of the most powerful judicial positions in the country, but to a document written 230 years ago.

Gorsuch, a federal appellate judge based in Denver, promised that should he get through the confirmation process he would act as a “faithful servant” to what he called “the greatest charter of human liberty the world has ever known”. He was referring to the US constitution, the supreme law of the land drafted in 1787.

He was not being rhetorical. Gorsuch describes himself as an “originalist”, indicating that he places overwhelming importance on the original meaning of the constitution as it was understood by “we the people” at the time it was written.

That puts him in a very select group of judges – maybe no more than 30 – who identify themselves as “originalists”. What unites them is that they put as much emphasis on the original understanding of the US constitution as Christian fundamentalists say they put on the original wording of the Bible.

Until his death last year, one of the most prominent members of the group was Antonin Scalia, the supreme court justice whom Gorsuch is now lined up to replace. Scalia helped spread the word of originalism among conservative judges in the 1980s as a way of pushing back on what he considered to be the increasingly outlandish opinions of his progressive peers.

Judges were there, Scalia argued, not to make up their own laws or politically motivated judgments, but to cleave faithfully to the meaning of the framers’ writings as they were understood back in the 18th century by the American people.

“Originalists ask what the constitution meant at the time it was written, and then argue that the meaning is fixed – it doesn’t change because the world has changed and we now have new problems to deal with,” said Lawrence Solum, a professor at Georgetown Law who is a leading theorist of constitutional originalism.

David Feder, a Los Angeles-based lawyer, had first-hand experience of what that meant to Gorsuch in practice when he worked as his law clerk on the federal 10th circuit court of appeals. “Whenever a constitutional issue came up in our cases, [Gorsuch] sent one of his clerks on a deep dive through the historical sources. ‘We need to get this right,’ was the motto – and right meant ‘as originally understood’,” Feder recalled .. http://yalejreg.com/nc/the-administrative-law-originalism-of-neil-gorsuch/ .. recently in the Yale Journal of Regulation.

Even taking into account the modernizing influence of the amendments that have been made to the constitution – most recently .. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twenty-seventh_Amendment_to_the_United_States_Constitution .. a prohibition on changes to congresspeople’s salaries taking effect until the start of the next term for representatives, passed in 1992 – a strict adherence to the founding documents can prove tricky. In 1787, most transportation was by ship or horse, not by plane or motorcar; communication was on parchment and paper rather than through the internet and cellphones; gay marriage was beyond most people’s imagination.

Conundrums can arrive at the level of the word. Solum points out that the seventh amendment, adopted as part of the bill of rights in 1791, guarantees the right to a jury trial in civil cases where the amount in dispute rises above “twenty dollars”.

Trouble is, the word “dollar” actually referred to a Spanish silver coin that was the main form of currency in 1791. Similarly, the reference to “domestic violence” in article four of the constitution does not equate to spousal or child abuse as it would today but to riots or insurrections within the boundaries of a single state.

The world has changed in ways that two-centuries old documents cannot reach. “We have a freedom of speech provision, but when it was written, no one spoke over the internet,” Solum said.

Originalists grapple with these contradictions in different ways. In the case of Gorsuch, his approach appears to be to try to stick rigidly to the spirit of the original meaning of the constitution while adapting it to modern circumstances.

Advertisement

That makes him something of an unknown quantity: it is hard to predict how he would respond to crucial areas of jurisprudence. Take gay marriage, for example: in the unlikely even that it were to come before the supreme court again, would Gorsuch follow the line taken by Scalia, that gay marriage was not covered by the 14th amendment’s “privileges and immunities” clause because at the time the amendment was adopted in 1868, same-sex marriage was illegal?

Or would Gorsuch take the view that the original definition of who was entitled to the privilege of marriage could change as society changes? “The people who wrote the provision did not fully envision where it would take us,” Solum said. “Gorsuch could be in that camp: that the meaning of the words remains the same but the implications change as social norms change.”

There is no easy way to answer that question, as Gorsuch has participated in no same-sex marriage case law that would provide clues.

If confirmed, though, Gorsuch could prove to be an unreliable ally from Trump’s point of view, at least on occasion. Certainly, his accent on sticking to the meaning of the past brings him generally in line with the rightwing conservatism of the Republican party.

But originalists like Gorsuch see themselves as fierce protectors of the checks and balances that lie at the core of the US constitution. And as such they have the potential to bristle at presidents seen to be overstepping the limits of their executive powers.

“It is certainly possible that Donald Trump .. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/donaldtrump .. will try and do things that go well beyond the original understanding of executive power,” Solum said. “When that happens, the president should be ready to be surprised by his nominee’s response.”

Topics

https://www.theguardian.com/law/2017/feb/02/originalism-constitution-supreme-court-neil-gorsuch

Gorsuch's position in that SCOTUS immigration case suggests this article may not be far off the mark.

Despite Gorsuch, Supreme Court Remains Centrist

Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. administered the Constitutional Oath to Justice

Neil M. Gorsuch as his wife Marie Louise Gorsuch held the Bible at the Supreme

Court Building April 10. (Handout /)

NOAH FELDMAN

April 11 2017

With the swearing-in Monday of Justice Neil Gorsuch, the U.S. Supreme Court's configuration shifts to a 4-4 balance with a single centrist justice as the swing vote. If that sounds familiar, it should. It's been the normal state of affairs since 1986, when Justice Antonin Scalia joined, and on some issues all the way back to Richard Nixon's administration.

This time, of course, the configuration results from the Republican Senate's unprecedented and successful gamble to block President Barack Obama from filling Scalia's seat. His pick, Judge Merrick Garland .. http://www.courant.com/topic/crime-law-justice/justice-system/merrick-garland-PEGPF00168-topic.html , would have given the liberals a clear, consistent majority for the first time since the days of Chief Justice Earl Warren — unless and until President Donald Trump had the chance to replace one of the court's liberals.

It's nevertheless worth exploring the fascinating phenomenon of the enduring centrist court, and asking the question: Is it an accident? Or is it a feature of the Supreme Court in its current condition, when liberal and conservative justices are all activists?

The court's composition follows from a feature of constitutional design that includes some luck, namely that justices can serve for life and that the president who's in office gets to nominate the replacement (or used to). If the presidency changes parties with some regularity, and justices retire or die on an arbitrary schedule, that should ensure some balance.

The first condition has been fulfilled since the death of Franklin Roosevelt, who was elected four times and picked an astonishing nine justices if you include a chief who was already on the court. If you start with Harry Truman, the longest run of one party in the presidency has been 12 years, for two terms of Ronald Reagan and one for George H.W. Bush. Otherwise, the presidency has typically flipped parties every eight years, with Jimmy Carter's single term leading to the only shorter flip.

The second condition hasn't been fulfilled perfectly, because some justices retire when they like the president who will replace them. But there has been surprisingly little of that strategic choice by the justices, despite the politicization of the process. Chief Justice William Rehnquist died in office, as did Scalia. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor retired because of her husband's failing health.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg stayed on the court past Barack Obama's presidency despite being well into her 80s and having survived not one but two bouts with cancer. If that's not a rejection of the strategic approach, I don't know what is.

But beyond constitutional structure, there's another extraordinary, non-accidental fact about the centrist court: It's been maintained in large part by individual justices' drift to the center.

The most salient example is Justice Anthony Kennedy. He's the swing vote today, as he has been since O'Connor retired a decade ago. But for nearly 20 years before that, Kennedy wasn't perceived as the swing voter — O'Connor was. Kennedy was considered a reliable conservative, with a few outlying liberal opinions on equality for gay people and the abortion compromise in Casey v. Planned Parenthood.

It's not that Kennedy just seemed more liberal when O'Connor retired. He actually became more liberal. His liberal opinions in recent years on abortion and affirmative action prove this definitively. Each represented a real shift leftward from his earlier opinions on the same subject.

Kennedy's shift had internal theoretical motivations, no doubt, grounded in the development of his jurisprudence of equal dignity. But it also resulted from the natural impulse to influence and the power that comes from being the swing vote.

The court's way of setting precedent gives enormous power to the swing voter. If there's no majority opinion, the narrowest opinion for the result that gets five votes becomes controlling precedent.

Even if the swing voter joins the majority opinion and writes a separate concurrence, his or her narrow opinion has a way of becoming the majority opinion in future cases, as the other justices try to win the votes of the swing justice.

The upshot is that the center-most justice, measured by ideology, will always have an incentive to tack toward the middle under the existing system. For the moment, that is still Kennedy.

But when Kennedy is no longer in the center, some other justice may emerge to take center stage, literally.

I'm not guaranteeing a centrist court forever. But if Justices Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer can hold out until a Democratic president is elected, or if a Democratic Senate denies Trump any appointments until a Democrat replaces him, we may see the centrist Supreme Court remaining into the distant future.

Maybe the American people want it that way.

Noah Feldman, a professor of constitutional and international law at Harvard University and former clerk

to U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Souteris, writes for Bloomberg View, where this first appeared.

http://www.courant.com/opinion/op-ed/hc-op-feldman-neil-gorsuch-supreme-court-balance-0411-20170410-story.html

It was Plato who said, “He, O men, is the wisest, who like Socrates, knows that his wisdom is in truth worth nothing”

Join the InvestorsHub Community

Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.