| Followers | 9 |

| Posts | 1597 |

| Boards Moderated | 1 |

| Alias Born | 01/27/2014 |

Monday, April 10, 2017 3:53:12 PM

Print me a plane

For now, says Morris, “we have just scratched the surface”.

From the Institution of Mechanical Engineers at imeche.org - Print me a plane - 05 Apr 2017

Are 3D-printed parts ready for mission-critical applications? Few industries are as demanding as aerospace, so Lawrie Jones asks whether 3D printing is making the grade

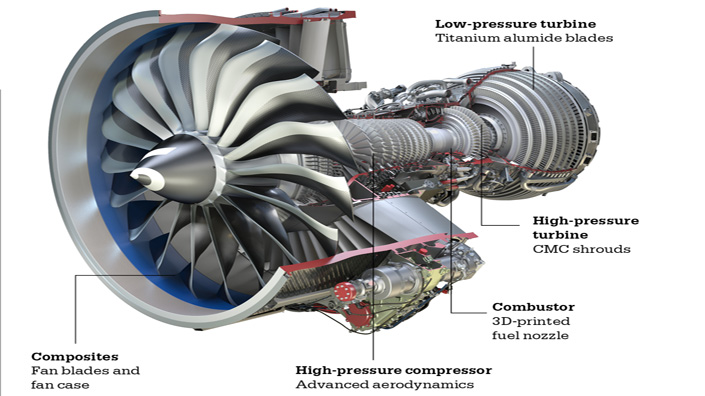

Greg Morris builds planes. Or rather, he builds parts for aircraft engines, together with his team at the GE Additive Centre in Cincinnati, Ohio. They don’t have forges or lathes, though. As the head of GE’s additive manufacturing department, Morris and his colleagues use 3D printing, changing what’s possible in aerospace engineering – one component at a time.

Last October, GE unveiled its ATP demonstrator powerplant, a propeller engine dubbed the Advanced Turboprop that uses more 3D-printed parts than any other engine in history. Working at the cutting edge of materials and design, 855 traditionally tooled parts will be replaced by just 12 printed ones.

In the final specification, up to 35% of the engine will be 3D-printed, including high-performance components such as sumps, bearing housings, frames and heat exchangers.

GE isn’t alone in this 3D printing business. Last June at the Berlin air show, Airbus unveiled Thor, or “Testing High-tech Objectives in Reality,” the world’s first fully 3D-printed aircraft. At only 4m long, it’s not big enough for paying passengers, but another example of pushing the boundaries of aircraft construction. And Rolls-Royce, with its Trent XWB-97 engine experimenting with 3D-printed parts, isn’t dragging its feet either.

3D printing “frees the engineer of the traditional limitations” of conventional manufacturing methods, says Morris – like milling, casting, forging, turning and welding solid blocks of material into the necessary shapes. These methods may be tried and tested, but they are also complicated and wasteful, with up 10kg of raw product needed for every kilogram of finished part.

With new additive manufacturing technologies, a 3D printer builds up the part layer-on-layer – in powdered plastics, carbon, aluminium, titanium or stainless steel, slowly forming complex shapes that would be impossible to make with traditional methods. The machines use only the materials they need, cutting waste massively. The potential isn’t in recreating what we already have in new ways, it’s about rethinking everything from the ground up.

____________________________________________________________________

At the British company GKN Aerospace, Robert Sharman, head of additive manufacturing, says that the current focus for the business isn’t on 3D-printed parts themselves but “on getting the materials properties right – without that, it’s useless”. And, he adds, there is another challenge to overcome to get 3D printing widely accepted – that around certification and qualification, which could “stagnate the adoption of the technology”.

The aircraft industry moves in cycles, with lead times for airframes and engines measured in decades. The genuinely transformative opportunities of additive techniques will only be fully explored when suppliers are given what Sharman calls a “clean sheet,” and start actively designing with 3D printing in mind. “Too many people are trying to create parts that we already make today,” he says. “For me, it’s about doing what you can’t do today.” With its new Advanced Turboprop engine, GE is the first to the party, but it won’t be the last.

__________________________________________________________________

The need to advance the knowledge base is something that engineers are aware of. “Our experience in mass-producing the nozzle tip for the LEAP jet engine has been invaluable in learning how to certify the machines for mass-production of a highly-regulated product,” says Morris. This information isn’t being locked away within GE, it’s being shared across the company’s entire supply chain. Morris believes better materials and processes and time in the air will all help to convince the regulators that 3D-printed parts are a viable alternative.

While industry experts such as Morris, Todd and Sharman are positive and enthusiastic about 3D printing in the mid-term, they think it won’t completely replace traditional casting. “The technology must buy its way onto a sophisticated engine,” says Morris.

Todd sees the challenge in involving all levels – informing those in the boardroom, re-skilling those on the shop floor and inspiring the next generation who will enter the industry. The new industrial revolution is coming – and 3D printing could drastically change the way we build planes. For now, says Morris, “we have just scratched the surface”.

For now, says Morris, “we have just scratched the surface”.

From the Institution of Mechanical Engineers at imeche.org - Print me a plane - 05 Apr 2017

Are 3D-printed parts ready for mission-critical applications? Few industries are as demanding as aerospace, so Lawrie Jones asks whether 3D printing is making the grade

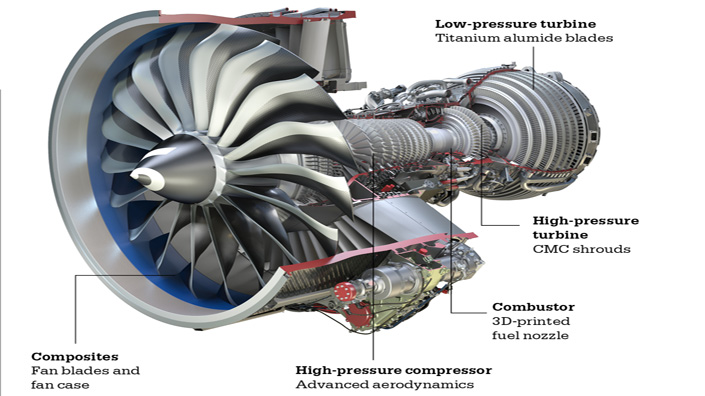

Greg Morris builds planes. Or rather, he builds parts for aircraft engines, together with his team at the GE Additive Centre in Cincinnati, Ohio. They don’t have forges or lathes, though. As the head of GE’s additive manufacturing department, Morris and his colleagues use 3D printing, changing what’s possible in aerospace engineering – one component at a time.

Last October, GE unveiled its ATP demonstrator powerplant, a propeller engine dubbed the Advanced Turboprop that uses more 3D-printed parts than any other engine in history. Working at the cutting edge of materials and design, 855 traditionally tooled parts will be replaced by just 12 printed ones.

In the final specification, up to 35% of the engine will be 3D-printed, including high-performance components such as sumps, bearing housings, frames and heat exchangers.

GE isn’t alone in this 3D printing business. Last June at the Berlin air show, Airbus unveiled Thor, or “Testing High-tech Objectives in Reality,” the world’s first fully 3D-printed aircraft. At only 4m long, it’s not big enough for paying passengers, but another example of pushing the boundaries of aircraft construction. And Rolls-Royce, with its Trent XWB-97 engine experimenting with 3D-printed parts, isn’t dragging its feet either.

3D printing “frees the engineer of the traditional limitations” of conventional manufacturing methods, says Morris – like milling, casting, forging, turning and welding solid blocks of material into the necessary shapes. These methods may be tried and tested, but they are also complicated and wasteful, with up 10kg of raw product needed for every kilogram of finished part.

With new additive manufacturing technologies, a 3D printer builds up the part layer-on-layer – in powdered plastics, carbon, aluminium, titanium or stainless steel, slowly forming complex shapes that would be impossible to make with traditional methods. The machines use only the materials they need, cutting waste massively. The potential isn’t in recreating what we already have in new ways, it’s about rethinking everything from the ground up.

____________________________________________________________________

At the British company GKN Aerospace, Robert Sharman, head of additive manufacturing, says that the current focus for the business isn’t on 3D-printed parts themselves but “on getting the materials properties right – without that, it’s useless”. And, he adds, there is another challenge to overcome to get 3D printing widely accepted – that around certification and qualification, which could “stagnate the adoption of the technology”.

The aircraft industry moves in cycles, with lead times for airframes and engines measured in decades. The genuinely transformative opportunities of additive techniques will only be fully explored when suppliers are given what Sharman calls a “clean sheet,” and start actively designing with 3D printing in mind. “Too many people are trying to create parts that we already make today,” he says. “For me, it’s about doing what you can’t do today.” With its new Advanced Turboprop engine, GE is the first to the party, but it won’t be the last.

__________________________________________________________________

The need to advance the knowledge base is something that engineers are aware of. “Our experience in mass-producing the nozzle tip for the LEAP jet engine has been invaluable in learning how to certify the machines for mass-production of a highly-regulated product,” says Morris. This information isn’t being locked away within GE, it’s being shared across the company’s entire supply chain. Morris believes better materials and processes and time in the air will all help to convince the regulators that 3D-printed parts are a viable alternative.

While industry experts such as Morris, Todd and Sharman are positive and enthusiastic about 3D printing in the mid-term, they think it won’t completely replace traditional casting. “The technology must buy its way onto a sophisticated engine,” says Morris.

Todd sees the challenge in involving all levels – informing those in the boardroom, re-skilling those on the shop floor and inspiring the next generation who will enter the industry. The new industrial revolution is coming – and 3D printing could drastically change the way we build planes. For now, says Morris, “we have just scratched the surface”.

Join the InvestorsHub Community

Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.