Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.

you always have someone running around out there that doesnt belong !! i know he used to love pulling up the shrimp. i thought he never left canada ?

We called them Herring balls and the trick was to get close to them and cast into the ball. Some dolts used to go roaring into the ball and screw it all up. Jim and I use to go out of Nootka sound and troll to the halibut bar and jig for Halibut. We generally got out quota pretty quick, then back to trolling for salmon. We also used to fish the inside (between the mainland and the island), There we would go for crab and shrimp and of course troll for the smaller salmon. Great times. Then he moved to New Zealand. I have been there and the people are the nicest you would want to meet. RIP Brother

MONSTER CROC towers over BULL SHARK - Ivanhoe Crossing Kununurra, The Kimberley, WA

never be in the water near a bait ball....

https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=whale+almost+swallows+kayaker&docid=607992079047917670&mid=C37ABC527640806C105BC37ABC527640806C105B&view=detail&FORM=VIRE

wouldnt mind even living there..........enjoy fella's its been awhile since any of us posted here

peace man...........

500-pound goliath grouper eats shark as shocked Florida fishermen watch: 'He just sucked it in'

By Jennifer Earl

July 18, 2018

I wish that was around when I was commercial diving in the Keys straight out of college early to mid '70s,

we'd have def been participants pairing nicely with the gallons of beer consumed after a day of work in the water.

What could have been more reasonable to a 21 y.o.?

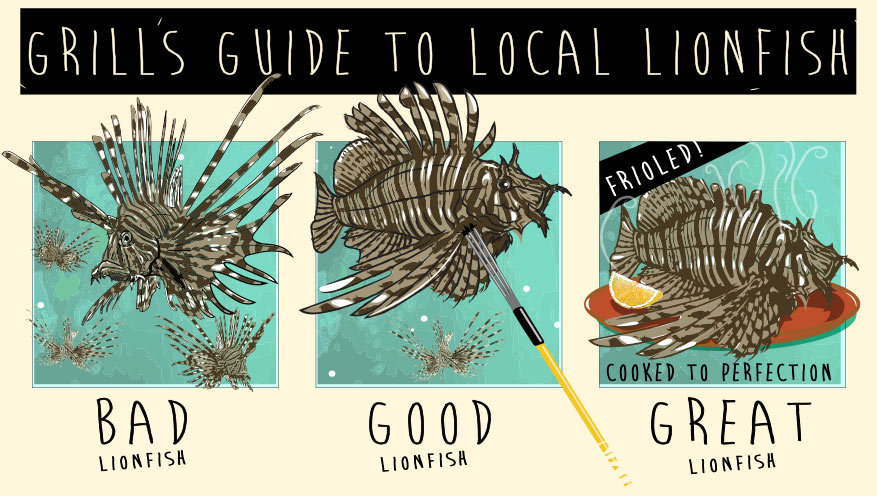

How to fillet a lion fish

Can Florida’s Lionfish Challenge rein in the venomous invasive? Maybe.

Michael DeRemer, a prize-winner of the state's Lionfish Challenge, removes lionfish from a cooler for a fish fry at Jim's Dive Shop in St. Petersburg on July 13. DeRemer caught three lionfish tagged by the state. MARTHA ASENCIO RHINE | Times

By Justin Trombly

July 16, 2018 at 05:52 AM

Submerged in the Gulf of Mexico, Michael DeRemer spotted the yellow glint of the lionfish’s tag.

The 62-year-old Largo diver had been looking for grouper that June day, but the tag changed things: It meant the spiny seafarer was a lucrative target — one that would yield prizes as part of this year’s state Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Lionfish Challenge, the third since 2016.

So, he aimed his pole spear.

That specimen and two more DeRemer nabbed later won him $500, a GoPro camera and a shirt. Those are the kinds of incentives Florida is offering people to catch lionfish, a venomous Indo-Pacific native that has infested Florida’s coastal waters.

And though eradicating the species no longer seems like an option, the state’s initiative — which began in May and lasts until Labor Day — could help curb the invasive population where it may be most noticeable: local reefs.

"It’s really more like weeding the garden," said Stephanie Green, a marine ecologist at the University of Alberta who studies the species.

• • •

Green’s analogy was echoed by others researchers: If you want the notoriously gluttonous lionfish to stop eating everything at the reef nearby, you have to cull them regularly.

That’s why the Lionfish Challenge is an improvement to Matthew Johnston, a biology professor at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale.

For years, sporadic tournaments have been organized across the state to hunt lionfish, likely doing little in the long term to combat the species. "Consistent, monthly, concerted effort throughout the entire area" is how to best control the populations, Johnston said.

Johnston and other experts — though not opposed to the contest — also expressed skepticism or uncertainty about just how much the state’s effort can address the issue on a wider scale.

"We shouldn’t be lulled into thinking that this will solve the problem," he said.

• • •

The task isn’t hard just because there are so many lionfish.

Lionfish live as far as 1,000 feet below the surface, and divers can descend only between 100 and 120 feet before risks arise. That means most divers target lionfish in relatively shallow water, on reefs. But those killed by divers can be replaced within months, either by adults that have migrated from nearby, seizing the vacuum, or by larvae that have floated in on ocean currents.

"(Lionfish) have this deep-water refuge where they can go down and spawn," said LeRoy Creswell, who works for the University of Florida-operated Florida Sea Grant, the regional leg of a national research program.

"You always have this source of new recruits coming up to the surface," he said. "You can have all the derbies and challenges and awards … but it’s just the tip of the iceberg."

• • •

The Lionfish Challenge works like this:

Any participant who submits 25 lionfish (the recreational category) or 25 pounds of the species (the commercial category) receives a shirt; a commemorative coin that allows the harvest of one extra spiny lobster per person per day during the July 25-26 season; and an entry in the conservation commission’s "Lionfish Hall of Fame."

Prizes get glitzier the more fish you bag. Turning in 400 lionfish wins you a customized ZooKeeper, a device well-known to anglers that’s designed hold 14 to 20 pounds of lionfish and protect from their venomous spines.

Along with raffles and trophies for the largest hauls, participants can win cash and other prizes for catching tagged lionfish, like DeRemer did.

The tagged fish — caught, labeled and released in public waters by the state beforehand — are new this year. The hope is that they act like Willy Wonka’s golden tickets, pushing more people to seek out the species. Lionfish aren’t normally desirable; their spines sting, making them a pain to clean and fillet. Only recently have they wound up on restaurant menus.

The number of participants and the number of harvested lionfish have increased since the effort began, conservation commission spokeswoman Hanna Tillotson said.

In 2016, 95 participants caught 16,609 lionfish; in 2017, 120 caught 26,454. As of July 10, 82 people had participated in this year’s iteration, catching 8,510 fish. The final totals are expected to overtake those of the first two years.

• • •

For his part, DeRemer was certain of one thing: "Those little guys are good to eat."

Outside Jim’s Dive Shop in St. Petersburg on a recent Friday, he was plucking strips of lionfish from a cooler, rolling them in a mound of seasoning and dropping them into a makeshift fryer for hungry guests inside.

He turned to check on his grub, revealing the back of the shirt he had won from the state: an illustration of a lionfish, its long spines fanning out over its body, red and white and deadly. The strips sizzled, and DeRemer scooped them into a tray. Golden brown.

http://www.tampabay.com/news/environment/wildlife/Can-Florida-s-Lionfish-Challenge-rein-in-the-venomous-invasive-Maybe-_169764438

Toxic algae: Once a nuisance, now a severe nationwide threat

storage.googleapis.com/afs-prod/media/media:48952a1ccc124df288f2bccd1f55ac58/800.jpeg

By JOHN FLESHER and ANGELIKI KASTANIS

November 16, 2017

MONROE, Mich. (AP) — Competing in a bass fishing tournament two years ago, Todd Steele cast his rod from his 21-foot motorboat — unaware that he was being poisoned.

A thick, green scum coated western Lake Erie. And Steele, a semipro angler, was sickened by it.

Driving home to Port Huron, Michigan, he felt lightheaded, nauseous. By the next morning he was too dizzy to stand, his overheated body covered with painful hives. Hospital tests blamed toxic algae, a rising threat to U.S. waters.

“It attacked my immune system and shut down my body’s ability to sweat,” Steele said. “If I wasn’t a healthy 51-year-old and had some type of medical condition, it could have killed me.”

He recovered, but Lake Erie hasn’t. Nor have other waterways choked with algae that’s sickening people, killing animals and hammering the economy. The scourge is escalating from occasional nuisance to severe, widespread hazard, overwhelming government efforts to curb a leading cause: fertilizer runoff from farms.

Pungent, sometimes toxic blobs are fouling waterways from the Great Lakes to Chesapeake Bay, from the Snake River in Idaho to New York’s Finger Lakes and reservoirs in California’s Central Valley.

Pungent, toxic algae is spreading across U.S. waterways, even as the government spends vast sums of money to help farmers reduce fertilizer runoff that helps cause it. An AP investigation finds algae has become a serious hazard in all 50 states. (Nov. 16)

Last year, Florida’s governor declared a state of emergency and beaches were closed when algae blooms spread from Lake Okeechobee to nearby estuaries. More than 100 people fell ill after swimming in Utah’s largest freshwater lake. Pets and livestock have died after drinking algae-laced water, including 32 cattle on an Oregon ranch in July. Oxygen-starved “dead zones” caused by algae decay have increased 30-fold since 1960, causing massive fish kills. This summer’s zone in the Gulf of Mexico was the biggest on record.

Tourism and recreation have suffered. An international water skiing festival in Milwaukee was canceled in August; scores of swimming areas were closed nationwide.

Algae are essential to food chains, but these tiny plants and bacteria sometimes multiply out of control. Within the past decade, outbreaks have been reported in every state, a trend likely to accelerate as climate change boosts water temperatures.

This June 29, 2016 aerial photo shows blue-green algae in an area along the St. Lucie River in Stuart, Fla.

“It’s a big, pervasive threat that we as a society are not doing nearly enough to solve,” said Don Scavia, a University of Michigan environmental scientist. “If we increase the amount of toxic algae in our drinking water supply, it’s going to put people’s health at risk. Even if it’s not toxic, people don’t want to go near it. They don’t want to fish in it or swim in it. That means loss of jobs and tax revenue.”

Many monster blooms are triggered by an overload of agricultural fertilizers in warm, calm waters, scientists say. Chemicals and manure intended to nourish crops are washing into lakes, streams and oceans, providing an endless buffet for algae.

Government agencies have spent billions of dollars and produced countless studies on the problem. But an Associated Press investigation found little to show for their efforts:

—Levels of algae-feeding nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus are climbing in many lakes and streams.

—A small minority of farms participate in federal programs that promote practices to reduce fertilizer runoff. When more farmers want to sign up, there often isn’t enough money.

—Despite years of research and testing, it’s debatable how well these measures work.

DEPENDING ON FARMERS TO VOLUNTEER

The AP’s findings underscore what many experts consider a fatal flaw in government policy: Instead of ordering agriculture to stem the flood of nutrients, regulators seek voluntary cooperation, an approach not afforded other big polluters.

Farmers are asked to take steps such as planting “cover crops” to reduce off-season erosion, or installing more efficient irrigation systems — often with taxpayers helping foot the bill.

The U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service, part of the Department of Agriculture, says it has spent more than $29 billion on voluntary, incentive-based programs since 2009 to make some 500,000 operations more environmentally friendly.

Jimmy Bramblett, deputy chief for programs, told AP the efforts had produced “tremendous” results but acknowledged only about 6 percent of the nation’s roughly 2 million farms are enrolled at any time.

In response to a Freedom of Information Act request, the agency provided data about its biggest spending initiative, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQIP, which contracts with farmers to use pollution-prevention measures and pays up to 75 percent of their costs.

An AP analysis shows the agency paid out more than $1.8 billion between 2009 and 2016 to share costs for 45 practices designed to cut nutrient and sediment runoff or otherwise improve water quality.

A total of $2.5 billion was pledged during the period. Of that, $51 million was targeted for Indiana, Michigan and Ohio farmers in the watershed flowing into western Lake Erie, where fisherman Steele was sickened.

Yet some of the lake’s biggest algae blooms showed up during those seven years. The largest on record appeared in 2015, blanketing 300 square miles — the size of New York City. The previous year, an algae toxin described in military texts as being as lethal as a biological weapon forced a two-day tap water shutdown for more than 400,000 customers in Toledo. This summer, another bloom oozed across part of the lake and up a primary tributary, the Maumee River, to the city’s downtown for the first time in memory.

The type of phosphorus fueling the algae outbreak has doubled in western Lake Erie tributaries since EQIP started in the mid-1990s, according to research scientist Laura Johnson of Ohio’s Heidelberg University. Scientists estimate about 85 percent of the Maumee’s phosphorus comes from croplands and livestock operations.

NRCS reports, meanwhile, claim that conservation measures have prevented huge volumes of nutrient and sediment losses from farm fields.

Although the federal government and most states refuse to make such anti-pollution methods mandatory, many experts say limiting runoff is the only way to rein in rampaging algae. A U.S.-Canadian panel seeking a 40 percent cut in Lake Erie phosphorus runoff wants to make controlling nutrients a condition for receiving federally subsidized crop insurance.

“We’ve had decades of approaching this issue largely through a voluntary framework,” said Jon Devine, senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council. “Clearly the existing system isn’t working.”

Farmers, though, say they can accomplish more by experimenting and learning from each other than following government dictates.

“There’s enough rules already,” said John Weiser, a third-generation dairyman with 5,000 cows in Brown County, Wisconsin, where nutrient overload causes algae and dead zones in Lake Michigan’s Green Bay. “Farmers are stewards of the land. We want to fix the problem as much as anybody else does.”

The Environmental Protection Agency says indirect runoff from agriculture and other sources, such as urban lawns, is now the biggest source of U.S. water pollution. But a loophole in the Clean Water Act of 1972 prevents the government from regulating runoff as it does pollution from sewage plants and factories that release waste directly into waterways. They are required to get permits requiring treatment and limiting discharges, and violators can be fined or imprisoned.

In this Sept. 13, 2016 photo, Brent Peterson, who promotes runoff prevention in eastern Wisconsin’s Lower Fox River watershed, stands beside a creek in Brown County, Wis.

Those rules don’t apply to farm fertilizers that wash into streams and lakes when it rains. Congress has shown no inclination to change that.

Without economic consequences for allowing runoff, farmers have an incentive to use all the fertilizer needed to produce the highest yield, said Mark Clark, a University of Florida wetland ecologist. “There’s nothing that says, ‘For every excessive pound I put on, I’ll have to pay a fee.’ There’s no stick.”

Some states have rules, including fertilizer application standards intended to minimize runoff. Minnesota requires 50-foot vegetation buffers around public waterways. Farmers in Maryland must keep livestock from defecating in streams that feed the Chesapeake Bay, where agriculture causes about half the nutrient pollution of the nation’s biggest estuary.

But states mostly avoid challenging the powerful agriculture industry.

Wisconsin issues water quality permits for big livestock farms, where 2,500 cows can generate as much waste as a city of 400,000 residents. But its Department of Natural Resources was sued by a dairy group this summer after strengthening manure regulations.

The state’s former head of runoff management, Gordon Stevenson, is among those who doubt that the voluntary approach will be enough to make headway with the algae problem.

“Those best-management practices are a far cry from the treatment that a pulp and paper mill or a foundry or a cannery or a sewage plant has to do before they let the wastewater go,” he said. “It’s like the Stone Age versus the Space Age.”

QUESTIONABLE RESULTS

Do the anti-pollution measures subsidized by the government to the tune of billions of dollars actually work?

Agriculture Department studies of selected watersheds, based largely on farmer surveys and computer models, credit them with dramatic cutbacks in runoff. One found nitrogen flows from croplands in the Mississippi River watershed to the Gulf of Mexico would be 28 percent higher without those steps being taken.

Critics contend such reports are based mostly on speculation, rather than on actually testing the water flowing off fields.

Although there is not a nationwide evaluation, Bramblett said “edge of field” monitoring the government started funding in 2013 points to the success of the incentives program in certain regions.

Federal audits and scientific reports raise other problems: Decisions about which farms get funding are based too little on what’s best for the environment; there aren’t enough inspections to ensure the measures taken are done properly; farm privacy laws make it hard for regulators to verify results.

It’s widely agreed that such pollution controls can make at least some difference. But experts say lots more participation is needed.

“The practices are completely overwhelmed,” said Stephen Carpenter, a University of Wisconsin lake ecologist. “Relying on them to solve the nation’s algae bloom problem is like using Band-Aids on hemorrhages.”

The AP found that the incentives program pledged $394 million between 2009 and 2016 for irrigation systems intended to reduce runoff — more than on any other water protection effort.

In arid western Idaho, where phosphorus runoff is linked to algae blooms and fish kills in the lower Snake River, government funding is helping farmer Mike Goodson install equipment to convert to “drip irrigation” rather than flooding all of his 550 acres with water diverted from rivers and creeks.

But only 795 water protection contracts were signed by Idaho farmers between 2014 and 2016, accounting for just over 1 percent of the roughly 11.7 million farmland acres statewide. Even if many farmers are preventing runoff without government subsidies, as Bramblett contends, the numbers suggest there’s a long way to go.

Goodson says forcing others to follow his example would backfire.

“Farmers have a bad taste for regulatory agencies,” he said, gazing across the flat, wind-swept landscape. “We pride ourselves on living off the land, and we try to preserve and conserve our resources.”

But allowing farmers to decide whether to participate can be costly to others. The city of Boise completed a $20 million project last year that will remove phosphorus flowing off irrigated farmland before it reaches the Snake River.

Brent Peterson spends long days in a mud-spattered pickup truck, promoting runoff prevention in eastern Wisconsin’s Lower Fox River watershed, where dairy cows excrete millions of gallons of manure daily — much of it sprayed onto cornfields as fertilizer.

The river empties into algae-plagued Green Bay, which contains less than 2 percent of Lake Michigan’s water but receives one-third of the entire lake’s nutrient flow. Farmers in the watershed were pledged $10 million from 2009 to 2016 to help address the problem, the AP found.

Peterson, employed by two counties with many hundreds of farms, has lined up six “demonstration farms” to use EQIP-funded runoff prevention, especially cover crops.

“This is a big step for a lot of these guys,” he said. “It’s out of their comfort zone.”

And for all the money devoted to EQIP, only 23 percent of eligible applications for grants were funded in 2015, according to the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition.

Funding of the incentives program has risen from just over $1 billion in 2009 to $1.45 billion last year. The Trump administration’s 2018 budget proposes a slight cut.

“It sounds like a lot, but the amount of money we’re spending is woefully inadequate,” said Johnson of Heidelberg University.

ALGAE PLAGUE SPREADS

While there’s no comprehensive tally of algae outbreaks, many experts agree they’re “quickly becoming a global epidemic,” said Anna Michalak, an ecologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science at Stanford University.

A rising number of water bodies across the U.S. have excessive levels of nutrients and blue-green algae, according to a 2016 report by the Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Geological Survey. The algae-generated toxin that sickened Steele in Lake Erie was found in one-third of the 1,161 lakes and reservoirs the agencies studied.

California last year reported toxic blooms in more than 40 lakes and waterways, the most in state history. New York created a team of specialists to confront the mounting problem in the Finger Lakes, a tourist magnet cherished for sparkling waters amid lush hillsides dotted with vineyards. Two cities reported algal toxins in their drinking water in 2016, a first in New York.

More than half the lakes were smeared with garish green blooms this summer.

Charter boat captain Dave Spangler holds a sample of algae from Maumee Bay in Lake Erie in Oregon, Ohio, on Sept. 15, 2017.

“The headlines were basically saying, ’Don’t go into the water, don’t touch the water,’” said Andy Zepp, executive director of the Finger Lakes Land Trust, who lives near Cayauga Lake in Ithaca. “I have an 11-year-old daughter, and I’m wondering, do I want to take her out on the lake?”

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is developing a system for compiling data on algae-related illnesses. A 2009-10 study tallied at least 61 victims in three states, a total the authors acknowledged was likely understated.

Anecdotal reports abound — a young boy hospitalized after swimming in a lake near Alexandria, Minnesota; a woman sickened while jet-skiing on Grand Lake St. Marys in western Ohio.

Signs posted at boat launches in the Hells Canyon area along the Idaho-Oregon line are typical of those at many recreation areas nationwide: “DANGER: DO NOT GO IN OR NEAR WATER” if there’s algae.

In Florida, artesian springs beloved by underwater divers are tainted by algae that causes a skin rash called “swimmer’s itch.” Elsewhere, domestic and wild animals are dying after ingesting algae-tainted water.

A year ago, shortly after a frolic in Idaho’s Snake River, Briedi Gillespie’s 11-year-old Chesapeake Bay retriever stopped breathing. Her respiratory muscles were paralyzed, her gums dark blue from lack of air.

Gillespie, a professor of veterinary medicine, and her veterinarian husband performed mouth-to-nose resuscitation and chest massage while racing their beloved Rose to a clinic. They spent eight hours pumping oxygen into her lungs and steroids into her veins. She pulled through.

The next day, Gillespie spotted Rose’s paw prints in a purplish, slimy patch on the riverbank and took samples from nearby water. They were laced with algae toxins.

“It was pretty horrendous,” Gillespie said. “This is my baby girl. How thankful I am that we could recognize what was going on and had the facilities we did, or she’d be gone.

https://apnews.com/8ca7048f5cff4b45a634296a358f7309/Toxic-algae:-Once-a-nuisance,-now-a-severe-nationwide-threat

Record-breaking hammerhead shark caught near Texas City

By Calily Bien

July 10, 2017, 7:25 am

Record-breaking hammerhead shark caught near Texas City on July 9, 2017. (Courtesy: Texas City Jaycees)

TEXAS CITY, Texas (KXAN) — There’s no doubt Tim McClellen will be framing the picture of him with the massive, record-breaking hammerhead shark he caught over the weekend.

McClellen won 1st place when he caught the 1,033-pound shark in the 55th Annual Texas City Jaycees Tackle Time Fishing Tournament on July 9. His catch smashed the 871-pound record set in 1980 in the Gulf of Mexico.

In a photo posted to Facebook by the Texas City Jaycees, the shark appears to be at least twice the length of McClellen’s height.

http://kxan.com/2017/07/10/record-breaking-hammerhead-shark-caught-near-texas-city/

90 percent of the world’s fisheries either overfished or fully exploited, new report finds

By Bridgette Wilcox

Monday, May 15, 2017

The ominous sight of empty fish nets is becoming all too common as reports show that nearly 90 percent of fisheries all over the world are either overfished or fully-fished; 31.5 percent of fish stocks are fished at a biologically unsustainable level, while 58.1 percent are already fully-fished, said the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Only 10.5 percent of fish stocks are still underfished; a sobering rate considering how many people around the world depend on fish for livelihood as well as a healthy food source. According to FAO, 57 million people around the world are involved in fish production. At the same time, fish makes up 17 percent of the world population’s intake of animal protein, and 6.7 percent of the total protein consumed. It’s also considered a top source for various beneficial vitamins, as well as omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, zinc, and iron.

China is seen as a major contributor to the terrifying depletion of fish in the oceans. The country, having exhausted their own resources, has (with the full support of their government) been reported to go further to fish in other countries’ waters, NYTimes.com noted. China has been involved in many maritime disputes; from as near as neighboring Philippines where their towering vessels stand off against local fishing boats to as far away as Argentina where a Chinese vessel was taken down after the local coast guard chased it down for illegal fishing.

Between the county’s massive population, purchasing power, and powerful fleet of almost 2,600 deep-sea fishing vessels, it is becoming an unstoppable force undermining the rest of the world’s sustainable fishing efforts.

China’s aggressive fishing activities are exacerbated by smaller-scale but equally irresponsible fishing practices from countries around the world, leading to a startling decline in fish populations. Earlier this year, scientists from the University of North Carolina found that 90 percent of predatory fish have been wiped out from Caribbean coral reefs due to overfishing. At the same time, researchers from the University of California-San Diego suggests that fishing operations in the Gulf of California are not sustainable on an economical or ecological scale, due to an overcapacity of fishing boats in the area.

Additionally, research published in the journal Science Advances warned that the one-two punch of climate change and commercial fishing could cause marine hotspots to lose many of their species, affecting what is currently considered by scientists to be “exceptional biodiversity”.

In a report on how fisheries impact global food security up to 2050, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) projected that by 2050 — assuming the current effectiveness of fishery management is maintained — global communities may still catch around 112 metric tons of fish. This, however, could destablize the ecosystem, placing risk on stocks of predatory fish. WWF called for a significant improvement in fisheries management, saying this is the only sustainable solution to increase global catch quantities and meet the continuing demand for seafood. Setting limits on total allowable catches, protecting habitats, and conserving stocks of predatory fish are part of effective fishery management, WWF said.

The FAO meanwhile has included marine rehabilitation in its Sustainable Development Goals. As part of its targets, by 2020, it aims to end overfishing, as well as illegal, unreported, unregulated, and destructive fishing practices. Like WWF, the FAO also aims to restore fish stocks through science-based management plans.

Get more news on the state of our oceans on WaterWars.news.

Sources include:

FAO.org

NYTimes.com

UNCNews.UNC.edu

ScienceDaily.com

Advances.ScienceMag.org

WorldWildLife.org

http://www.naturalnews.com/2017-05-15-90-percent-of-the-worlds-fisheries-fully-exploited-or-facing-collapse-warns-new-report.html

World's Biggest Sockeye Run Shut Down as Wild Pacific Salmon Fight for Survival

Dr. David Suzuki

Sep. 21, 2016 11:28AM EST

Salmon have been swimming in Pacific Northwest waters for at least seven million years.

(please note: The underlined words are 'clickable' links when accessed via the link at the bottom of this page)

For as long as people have lived in the area, salmon have been an important food source and have helped shape cultural identities. But something is happening to Pacific coast salmon.

This year, British Columbia's sockeye salmon run was the lowest in recorded history. Commercial and First Nations fisheries on the world's biggest sockeye run on British Columbia's longest river, the Fraser, closed. Fewer than 900,000 sockeye out of a projected 2.2 million returned to the Fraser to spawn. Areas once teeming with salmon are all but empty.

Salmon define West Coast communities, especially Indigenous ones. The West Coast is a Pacific salmon forest. Today, salmon provide food and contribute to sustainable economies built on fishing and ecotourism. West Coast children learn about the salmon life cycle early in their studies.

Salmon migrations, stretching up to 3,000 kilometers, are among the world's most awe-inspiring. After spending adult lives in the ocean, salmon make the arduous trip up rivers against the current, returning to spawn and die where they hatched. Only one out of every thousand salmon manages to survive and return to its freshwater birthplace.

So what's going wrong? Climate change is amplifying a long list of stressors salmon already face. Sockeye salmon are sensitive to temperature changes, so higher ocean and river temperatures can have serious impacts. Even small degrees of warming can kill them. Low river flows from unusually small snowpacks linked to climate change make a tough journey even harder.

Oceans absorb the brunt of our climate pollution—more than 90 percent of emissions-trapped heat since the 1970s. Most warming takes place near the surface, where salmon travel, with the upper 75 meters warming 0.11 C per decade between 1971 and 2010. Although ocean temperatures have always fluctuated, climate change is lengthening those fluctuations. A giant mass of warmer-than-average water in the Pacific, known as "the blob," made ocean conditions even warmer, with El Niño adding to increased temperatures. Salmon have less food and face new predators migrating north to beat the heat.

Beyond creating poor environmental conditions for salmon, climate change increases disease risks. Warm conditions have led to sea lice outbreaks in farmed and wild salmon, and a heart and muscle inflammatory disease has been found in at least one farm. Scientists researching salmon movement through areas with farms are finding wild fish, especially young ones, with elevated parasite levels. Diseases that cause even slight deficiencies in swimming speed or feeding ability could make these marathon swimmers easy prey.

EcoWatch

@EcoWatch

#Salmon Farms Are Destroying Wild Salmon Runs, First Nations Say http://rbl.ms/2bc8gGT @seashepherd @pamfoundation @foodandwater

11:21 AM - 22 Aug 2016

161 Retweets

113 Likes

Some question whether wild salmon will remain a West Coast food staple. For the first time, the Monterey Bay Aquarium's Seafood Watch program has advised consumers to avoid buying chinook and coho from four South Coast fisheries. Researchers also predict changing conditions will drive important food fish north by up to 18 kilometers a decade.

Disappearing salmon don't just affect humans but all coastal ecosystems and wildlife. Eighty-two endangered southern resident killer whales depend on chinook salmon to survive. As chinook stocks go down, the likelihood that these whales could become extinct goes up.

Although the federal government has committed to implement recommendations from Justice Bruce Cohen's inquiry into Fraser River sockeye and to follow the Wild Salmon Policy, reversing this dire situation will take widespread concerted and immediate action. A weak provincial climate plan that fails to meet emissions targets and acceptance of new ocean-based fish farm applications won't help wild salmon. We need to move fish farms out of the water and onto land.

Salmon are resilient and have survived ice ages and other challenges over millions of years. They've survived having their streams paved over. They've survived toxins dumped into their environments. The question is, can they—and the ecosystems that depend on them—survive climate change and fish farms and all the other stressors humans are putting on them?

http://www.ecowatch.com/wild-salmon-climate-change-2011395747.html

good memories

Lucky man, 4 of us went to the mid Keys

out of college in the early seventies for two years to get our ya ya's out before strapping on the ball and chain. Our main passion on our time off was to troll the weed lines 10 miles out for dolphin, good stuff.

A year after we left the tarpon moved in and have never really left. That drew guys with serious money down there, Andy Granatelli bought the property with the 1920's style house on stilts we rented and built a palace in it's place all because of the shift in the tarpon. Always kind of pizzed me off the way that worked out.

always salt water around.....kings are in Droves right now offshore,,,,,inshore there in the shallows, just look for big swirls and chase em

lol, just got home, are you talking about the book

or that time of year in general? Heck, it's always that time of year down your way isn't it?

thanks for the post

Exclusive Photos of the First Ever Great White Shark Caught from a Florida Beach

by Zach Miller

2 days ago

Florida fishermen make a historic great white capture on beach in Florida.

Gabriel Smeby and Derrick Keeny were bundled up on an undisclosed Florida beach, doing what they and their Dark Side Sharkers crew have been doing for decades between them, shark fishing. But on this chilly, early March night, they had no idea that they would be entering the history books of land-based shark fishing.

After deploying three rods with their bait of choice for the night (bonito) via kayak, about 300 yards from the shoreline of the beach, Gabe, Derrick and the rest of the crew bundled up and began the long, tedious waiting game that is land-based shark fishing. They were there for the duration of the night, no matter how cold, miserable, or boring it got.

After an oddly silent night, and patiently waiting for the better part of seven hours, Derrick’s 80 wide rod tip started to bounce a bit. Whatever was gnawing at his bonito on the other end was acting very strange. It was picking up and dropping the bait repeatedly while staying inside a relatively small area. They immediately thought that it was “the curse of the nurse,” better known as a nurse shark for all you non-sharkers. But once they had confidence that the fish playing with their bonito way out off the beach in the cold, quiet night air had finally taken the entire bait, Derrick reeled tight on his line, engaging the circle hook into the unknown assailant’s mouth. The battle had finally begun…

Derrick watched as a tremendous amount of line began disappearing off the spool of his reel. They immediately knew that they did not have the lethargic nurse shark hooked that they originally believed. A long slow, steady run made the fish mad, while the crew sat idlely by wondering what they may have hooked. A big bull shark? A tiger maybe? Possibly even a large hammerhead? Their minds were wandering through the forest of possibilities that presented themself during this particular battle, but before they could put their minds at ease, they had to stop it first.

After about 15 minutes of non-stop pulling, the mystery fish had finally tired out a bit, allowing them to begin gaining all the line they lost back onto the reel. Little by little, the spool began filling back up with all the line that was lost, and there was a sense of relief amongst the crew as they knew their chances of landing this beast had dramatically increased with the gaining of line.

About 45 minutes had elapsed when they saw the swivel attached to their leader rise out of the dark wash, and they knew the fish was right there in front of them. The rest of the crew rushed the surf with flashlights to try to spot and identify the beast they had been battling, when a dorsal broke the surface.

“DUSKY!” Someone yelled (which is very rare shark to see near the beach these days). But then the tail rose about six feet behind the dorsal, and nobody was sure what they were looking at anymore.

The crew rushed the surf to grab the leader, with Derrick still up on the beach working the rod, wondering what was happening in the wash.

“WHITE! IT’S A WHITE!” The crew began to yell up the beach toward Derrick. “A WHITE?! A GREAT WHITE?!” Derrick yelled as he de-harnessed and ran down the beach with the camera.

Indeed it was, the rarest of sharks, and the Dark Side Sharkers had just caught one, the only one to EVER be caught from shore in Florida. The shark at the end of Derrick’s line was one of only four known to have been landed from the beach in the entire United States.

The crew began working quickly to remove the circle hook from the corner of its mouth while somebody in the background kept snapping photos as fast as they could while they were working on prepping the shark for release in the wash zone. While they worked on removing the hook, one of the crew members got a NOAA shark tag and tagged the shark right underneath its dorsal (as per code), making it the only great white shark ever tagged from a beach.

In what seemed like an eternity, but in reality was only a minute and a half, they were pushing the juvenile male great white back out into deeper water, walking with it up until they got to about waist deep water, to make sure he swam off safely.

Circle hook in sharks mouth

Inserting NOAA tag

Derrick, Gabe and the rest of the crew began to lose their minds as the fish swam away, trying to register what had just happened to them on this fateful night. They have been around the sport for a long time, and they knew the significance of this catch, and its place in shark fishing history, as well as how valuable an encounter like this is in the science community.

Releasing the shark

Great white shark sightings have been on the rise in recent years, especially in the state of Florida, which lends credence to the fact that worldwide conservation attempts to protect great white stocks may indeed be working. And with tens of thousands of baits fished by land-based shark fisherman in the state of Florida each year alone, this is the first confirmed great white capture that has ever occurred.

It really goes to show that if you have baits soaking in the water, you never know what you are going to catch. After all, the ocean doesn’t have any fences.

http://www.wideopenspaces.com/first-ever-great-white-shark-caught-florida-beach-exclusive-pics/

Race For The Chase Is ON

Pick one driver per race, ANY DRIVER but YOU CAN ONLY USE HIM 1 TIME...

person with most points wins

anyone forgets to pick gets DANICA'S SCORE.

no pick for 2 weeks YOU WILL BE DELETED

PRIZE....30 day Membership.

Tiebreaker:

1.most 1st places

2.if still tied: most points during individual races starting with Homestead and working backwards until the tie is broken

http://investorshub.advfn.com/A-Sprint-Cup-Challenge-3206/

Rare wahoo catch could be a first

50-pound wahoo landed by Eric Kim off Southern California is thought to be the first genuine catch of the species in U.S. Pacific Coast waters

By Pete Thomas

September 03, 2014

Eric Kim poses with 50-pound wahoo; photo by Amy Elliott/Balboa Angling Club

Of all the rare sightings and catches during this warm-water summer off Southern California, there’s only one “first” that we’re aware of, and it involves the catch of a 50-pound wahoo last Saturday about 10 miles off Orange County.

Eric Kim was on a tuna-fishing trip with friends aboard the private sportfisher Joker and trolling a large Rapala lure when the wahoo (ono) struck.

“I just thought it was a lone dorado or tuna, but then I felt the weight and thought this is actually a better fish,” Kim told Phil Friedman of PFO Radio. “I got it to color and we couldn’t believe it. It was a freaking wahoo.”

This has been the best summer fishing season off Southern California in decades, thanks to an abundance of yellowfin tuna and dorado (mahi-mahi) that has added a Mexican flavor to the local fishing experience.

The catch of a 50-pound wahoo off Southern California was no joke; photo by Amy Elliott/Balboa Angling Club

Those fish are far more common in Mexican waters, but appear off Southern California during warm-water events such as an El Niño.

Surface temperatures offshore range from about 72 to 76 degrees, well above normal. This has allowed exotic species of fish, and even some marine mammal species, to venture much farther north than their typical range.

But wahoo, which are found regularly in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez and off southern Baja California, simply do not migrate this far north.

Milton Love, a UC Santa Barbara scientist and author of “Certainly More Than You Want to Know About the Fishes of the Pacific Coast,” said Wednesday that Kim’s wahoo is believed to be the first genuine catch of a wahoo in the Eastern Pacific north of the U.S.-Mexico border.

“I have been waiting for an official U.S. record for years,” Love stated via email, adding that previously, the farthest northern catch was 130 miles south of the border.

Love is not counting a wahoo caught inside Los Angeles Harbor in the winter of 2010. That probably involved a fish that was brought into the harbor via boat or ship, because there’s little chance that a species that resides in tropical and sub-tropical seas could swum so far north at that time of year.

Wahoo, believed to be the world’s fastest fish, are extremely popular for their fight and the high quality of their flesh.

Kim was fishing with Capt. George Garrett, Ted Royal, and Zach Murtaugh. The wahoo, which measured 60 inches and had a girth of 22 inches, was weighed and photographed by Amy Elliott at the Balboa Angling Club scale in Newport Beach.

“They were amazed,” Elliott said. “It was Zach’s birthday and they were all having a ball catching dorado and tuna. They could not catch enough fish; it was one after another.”

Said Kim of seeing the wahoo come over the rail: “We were all tripping out. It took two nice runs. We got it to color and then my buddies, Zach and Ted … as soon as they put the gaff in it, it was all smiles, man. All smiles.”

http://www.grindtv.com/outdoor/excursions/post/rare-wahoo-catch-first/

MUST SIGN UP BY SEASON START...

The King of the Hill NFL Football Pool starts the weekend of Sunday, Sept. 7th....#board-2915

Win a 1 year subscription and more!!

It's a FREE board so anyone can join in the fun!!

Complete rules are in the iBox.....#board-2915 and sticky notes.

The first week We will accept picks right up to the start time of the first game on Monday night. After week #1, all picks must be in by Sunday at 1:00pm ET.

The weekly schedule is always listed on a sticky note.

Good luck!!

Seminole Red

Golf's Major Championships (GMC)

http://investorshub.advfn.com/Golfs-Major-Championships-GMC-2442/

FEDEX Cup is open for business

The top 25 in Fedex points are grouped into 5 tiers of 5 each and the remaining 100 golfers are in tier 6.

Fedex Cup player Tiers:

http://investorshub.advfn.com/boards/read_msg.aspx?message_id=105389890

Rules:

1. You pick 10 players for the 4 week tournament. You can only pick 1 player from each of the first 5 tiers. The other 5 players you pick from tier 6. You can pick all 10 player from tier 6 if you wish. Just no more than 1 each from the first 5 tiers.

2. Teams must be submitted prior to the first group teeing off on Thursday August 21st.

3. Must have fun

4. The winner will be the team with the highest total FedEx points at the end of the Tour Championship

5. Points will be deducted for spelling mistakes and poor punctuation.

6. All of Fred's decisions are final.

7. No gimmees or mulligans allowed.

8. Void where prohibited.

The 2014 British Open Pool is now open for business!!!

Tee times start at 1:25 AM Thursday

http://investorshub.advfn.com/boards/read_msg.aspx?message_id=104264137

1. You pick 5 players for the tournament. You can only pick 1 player from the top 5 in the world ranking. The top 5 are Rose, Scott, Stenson, B

Watson and Kuchar.

You must also pick a tie breaker total score...even par for the 4 rounds is 288.

2. Teams must be submitted prior to the first group teeing off on Thursday July 17th.

3. Must have fun

4. The winner will be the team with the highest total dollar total at the end of the Tournament.

5. Points will be deducted for spelling mistakes and poor punctuation.

6. All of Fred's decisions are final.

7. No gimmees or mulligans allowed.

8. Void where prohibited.

9. Late entries will be allowed but you can only pick from players that have not teed off.

Early signs point to a strong, disruptive El Niño

Whales and fish are showing up in odd places, nesting pelicans are in dire straits, and experts are increasingly convinced that this will be a significant event

By Pete Thomas

June 15, 2014

Yellowfin tuna are being caught far north of their typical range this season. Photo by Mark Rayor

A developing El Niño in the equatorial Pacific has generated the usual predictions of drastic weather changes—some devastating, some beneficial—throughout the world.

There’s a 90 percent probability that an El Niño will form, according to some experts. That’s up considerably from previous predictions, but the main question at this point is whether this will be moderate El Niño or, more likely, a powerful warm-water event such as those in the early 1980s and late ’90s.

(El Niño is characterized by unusually warm sea-surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific, whereas a La Niña is characterized by unusually cold temperatures. Strong El Niños typically alter weather patterns and can cause severe flooding in some areas, and droughts in others.)

The extent of El Niño’s strength won’t be known until late summer or fall. But based on several interesting signals, in the form of mammals, birds, and fish showing up where they don’t typically belong, it’s looking as though this El Niño is going to be a very powerful event.

Bryde’s whale mom and calf swim off Huntington Beach, California, in an extremely rare sighting; photo by ©Alisa Schulman-Janiger

Earlier this week two Bryde’s whales, a mother and calf, were photographed during two voyages on the same day off Huntington Beach, California, by researcher Alisa Schulman-Janiger.

Bryde’s whales, which measure to about 45 feet, are fairly common in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez. Sightings off California, however, are extremely rare.

Schulman-Janiger said that during NOAA surveys off California between 1991 and 2005, there was only one confirmed sighting of Bryde’s whales, which are also referred to as “tropical whales” because they prefer a warm environment.

Mahi-mahi, such as this one, are already being encountered just south of the U.S.-Mexico border. Photo by ©Pete Thomas

Less than a week earlier, a large pod of pilot whales showed off Dana Point on the Orange County coast. Pilot whales are found around the world, including off Mexico, but it had been nearly 20 years since they were last spotted off Southern California.

In late March, false killer whales, another ultra-rare visitor from warmer waters, thrilled whale watchers off Orange County.

Marine creatures showing in odd places often portends strange happenings in their environment

Pilot whales, which had not been seen off California in almost 20 years, were spotted off Dana Point on June 7. Photo by ©Frank Brennan/Dana Wharf Whale Watching

Fishermen are seeing signs, also. Anglers out of San Diego, on short excursions into Mexican waters, began catching yellowfin tuna in May. That’s unprecedented, according to some, as this sub-tropical species typically doesn’t show that far north until late summer, if at all.

During the El Niño in 1983 to 1984 and 1997 to 1998, however, yellowfin tuna migrated north early and, during the summer, were caught well into U.S. waters. (The 1997-98 El Niño generated heavy rainfall throughout California during the winter, and prolonged periods of rough seas exacted a heavy toll on sea lions and other mammals.)

“We’ve already started to see very unusual fish catches here,” Tim Barnett, marine research emeritus with the San Diego-based Scripps Institution of Oceanography, told KPBS. “The first yellowfin tuna was caught in May—that has never happened before to anybody’s recollection.

“And the other thing too is the first dorado (mahi-mahi)—first of June. That has never happened before. They really like the warm water and you normally don’t see them here until September.”

California brown pelicans, such as these two off Cabo San Lucas, are having a tough time in the Sea of Cortez, perhaps because of unseasonably warm water and a diminished bait fish supply. Photo by ©Pete Thomas

Barnett said the 1997 to 1998 El Niño, the biggest in a century, caused a northward shift of the entire fishery population, and he predicts a similar event is developing.

Water temperatures are unseasonably warm in some areas off Southern California, but only by a couple of degrees. Temperatures are significantly warmer than usual, however, off parts of western Mexico, including the Sea of Cortez.

This not only drives fish populations and some mammals beyond their typical range, but it causes shifts in bait fish populations.

This appears to have seriously affected California brown pelicans, about 90 percent of which breed and rear young in the Sea of Cortez.

Researchers recently discovered that the 2014 breeding season was so poor that one scientist referred to it as “a bust.”

False killer whales off Dana Point in late March, in a very rare sighting; photo by ©Pete Thomas

Sam Anderson, a UC Davis biologist and part of a survey team that visited traditional nesting sites, told ABC News that where they would typically encounter tens of thousands of breeding pairs of pelicans, there were only sparse numbers. Some nesting sites were alarmingly deserted.

“That’s what we call a failure, a bust. The bottom dropped out,” Anderson said.

Mark Rayor, who runs Jen-Wren Sportfishing in the Sea of Cortez, in Baja California’s East Cape region, said sardines and other types of bait fish are largely absent.

Rayor has logged water temperatures as high as 86 degrees, which is more typical of late July or August. He said blue marlin and sailfish, which generally begin to arrive in early August, are already showing in the offshore blue water. (Above NOAA chart shows where sea-surface temperatures are abnormally warm in portions of the Pacific.)

Anderson, however, was reluctant to place all of the blame for the pelicans’ plight on the developing El Niño.

“During most El Niño events we’ve seen, numbers of nesting attempts drop by at least half to two-thirds, and production goes down, too. But it drops from thousands to hundreds, not 10 or less.”

Whether El Niño is to blame or not, however, a powerful El Nino appears imminent, and the marine environment, on this side of the equator anyway, is already somewhat off-kilter.

And these are just some of the early messengers of change; they probably won’t be the last.

http://www.grindtv.com/outdoor/nature/post/early-signs-point-strong-disruptive-el-nino/

The 2014 US Open Pool is now open for business!!!

1. You pick 5 players for the tournament. You can only pick 1 player from the top 5 in the world ranking. The top 5 are Woods, Scott, Stenson, Watson and Kuchar (remember Woods is not playing).

You must also pick a tie breaker total score...even par for the 4 rounds is 280.

2. Teams must be submitted prior to the first group teeing off on Thursday June 12th.

3. Must have fun

4. The winner will be the team with the highest total dollar total at the end of the Tournament.

5. Points will be deducted for spelling mistakes and poor punctuation.

6. All of Fred's decisions are final.

7. No gimmees or mulligans allowed.

8. Void where prohibited.

9. Late entries will be allowed but you can only pick from players that have not teed off.

http://investorshub.advfn.com/boards/read_msg.aspx?message_id=103009235

The 2014 Masters Pool is now open for business!!!

http://investorshub.advfn.com/Golfs-Major-Championships-GMC-2442/

1. You pick 5 players for the tournament. You can only pick 1 player from the top 5 in the world ranking. The top 5 are Woods, Scott, Stenson, Day and Mickelson.

You must also pick a tie breaker total score...even par for the 4 rounds is 288.

2. Teams must be submitted prior to the first group teeing off on Thursday April 10th.

3. Must have fun

4. The winner will be the team with the highest total dollar total at the end of the Tournament.

5. Points will be deducted for spelling mistakes and poor punctuation.

6. All of Fred's decisions are final.

7. No gimmees or mulligans allowed.

8. Void where prohibited.

9. Late entries will be allowed but you can only pick from players that have not teed off.

been there but didn't fish there...this marina I remember cause they rent kayaks for the back water and have charters...there almost at the end of the island

http://www.castawayssanibel.com/marina.html

seminole red, any experience fishing sanibel island, looking for a private charter. never fished the gulf before. heading down last week of march. any help would be appreciated.

Rocco2

2014 Sprint Cup Challenge is ready for signups

WIN IHUB MEMBERSHIPS...SIGN UP NOW...ITS FREE

RULES ARE IN THE IBOX

http://investorshub.advfn.com/A-Sprint-Cup-Challenge-3206/

Sushi and parasites

many Japanese for ex: are well schooled at spotting parasites when eating sushi, are you?

http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=19929

lol !!! interesting thought, now i'll have a green italian with trails on her hand gestures !!!

hmmmm, a woman that glows in the dark...!

never liked it either. as far as i am concerned it has no taste. atleast to me anyway, but my wife swears its the greatest. wait until i tell her its now radio active !!!!

no sushi for me anyway...yuk....maybe smoked salmon

ALL Bluefin Tuna Caught In California Are Radioactive ... DO NOT EAT TUNA

October 2, 2013

http://thecitizenscolumn.com/general-ed/2013/10/2/all-bluefin-tuna-caught-in-california-are-radioactive-stay-away-from-sushi

Do NOT eat tuna. Period. ALL the bluefin tuna is radioactive. ALL. A year ago they told us they were surprised to find the fish contaminated after limited exposure to radioactive water. As this article points out, all of the bluefin tuna being caught now have spent their entire lives exposed to radioactive water. If you didn’t hear the warning a year ago, please hear it now.

Every bluefin tuna tested in the waters off California has shown to be contaminated with radiation that originated in Fukushima. Every single one.

Over a year ago, in May of 2012, the Wall Street Journal reported on a Stanford University study. Daniel Madigan, a marine ecologist who led the study, was quoted as saying, “The tuna packaged it up (the radiation) and brought it across the world’s largest ocean. We were definitely surprised to see it at all and even more surprised to see it in every one we measured.”

Another member of the study group, Marine biologist Nicholas Fisher at Stony Brook University in New York State reported, “We found that absolutely every one of them had comparable concentrations of cesium 134 and cesium 137.”

That was over a year ago. The fish that were tested had relatively little exposure to the radioactive waste being dumped into the ocean following the nuclear melt-through that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi plant in March of 2011. Since that time, the flow of radioactive contaminants dumping into the ocean has continued unabated. Fish arriving at this juncture have been swimming in contaminants for all of their lives.

Radioactive cesium doesn’t sink to the sea floor, so fish swim through it and ingest it through their gills or by eating organisms that have already ingested it. It is a compound that does occur naturally in nature, however, the levels of cesium found in the tuna in 2012 had levels 3 percent higher than is usual. Measurements for this year haven’t been made available, or at least none that I have been able to find. I went looking for the effects of ingesting cesium. This is what I found:

When contact with radioactive cesium occurs, which is highly unlikely, a person can experience cell damage due to radiation of the cesium particles. Due to this, effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and bleeding may occur. When the exposure lasts a long time, people may even lose consciousness. Coma or even death may then follow. How serious the effects are depends upon the resistance of individual persons and the duration of exposure and the concentration a person is exposed to.

The King of the Hill NFL Football Pool starts the weekend of Sunday, Sept. 8th....#board-2915

Win a 1 year subscription and more!!

It's a FREE board so anyone can join in the fun!!

Complete rules are in the iBox.....#board-2915 and sticky notes.

The NFL "King of the Hill" football pool starts Sunday, Sept. 8th. The rules are in the iBox here: #board-2915

This year’s deadline rules are here: #msg-91379978

It’s a FREE board so anyone can join and win free iHub subscriptions!

lolol...well, don't forget to have fun AND CATCH FISH

no, no, no and not yet... lol

Work and fishing has been about all I got time for.

has the wife been down to visit....she might like it there....

have ya been to the Edison and ford museum in ft. myers or the ringling museum in sarasota

job is interesting... I found a nice place close to the beach... just going home has been far and in between

trout are plentiful AND good to eat....hows the new job...did ya find a decent place to stay

|

Followers

|

56

|

Posters

|

|

|

Posts (Today)

|

0

|

Posts (Total)

|

15972

|

|

Created

|

10/21/03

|

Type

|

Premium

|

| Moderators Jim Bishop 100lbStriper frankie_fillet | |||

Salt Water Fishin is the topic here (Fresh water wimps are welcome too <BG>)... Please feel free to post your fishing adventures. You’re pictures are welcome too, you'll find plenty here. We hope you find this board both entraining and informative.

Salt Water Fishin is the topic here (Fresh water wimps are welcome too <BG>)... Please feel free to post your fishing adventures. You’re pictures are welcome too, you'll find plenty here. We hope you find this board both entraining and informative.

SALT WATER FISH IDENTIFICATION

http://www.identicards.com/Custom/saltwaterimages.htm

http://www.landbigfish.com/fish/default.cfm

Having trouble loading a pic??? #msg-12382674.

SALT WATER FISH IDENTIFICATION

http://www.identicards.com/Custom/saltwaterimages.htm

http://www.landbigfish.com/fish/default.cfm

Having trouble loading a pic??? #msg-12382674.

|

Posts Today

|

0

|

|

Posts (Total)

|

15972

|

|

Posters

|

|

|

Moderators

|

| Volume | |

| Day Range: | |

| Bid Price | |

| Ask Price | |

| Last Trade Time: |