Tuesday, February 10, 2015 8:09:29 PM

shtsqsh, Criticism of Germany's role .. a little reading, well worth a glance ..

1. German banks lent the most to Greece.

2. Germany has refused to be fiscally responsible toward the weaker economies of the eurozone.

3. Germany enjoyed "falling borrowing rates, investment influx, and exports boost thanks to Euro’s depreciation

"Germans claim this is mostly due to painful reforms over the past decade that turned the former sick man of Europe into its most competitive economy. But also important have been a weak currency, near-record-low borrowing costs and the willingness of its European neighbors to keep buying German goods—often with money effectively borrowed from Germany. Truly, it's an ill wind that blows no one any good.

On that basis, it's hard to dispute that the euro-zone bailout programs have so far proved remarkably good value for Germany."

.. 2011 WSJ .. http://www.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304803104576427971253989738

4. Germany has use the ECB to benefit itself rather to support the weaker economies (today) of the eurozone.

Some of above and all of below, with a couple of added inserts from links supplied, is verbatim here .. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_government-debt_crisis

"From 2000 to 2007, the periphery of the Eurozone (EZ) enjoyed a boom, while Germany did not. As a result, inflation in the periphery (and much else) of the EZ exceeded inflation in Germany by a significant and persistent amount. By 2007, this meant that Germany had become too competitive in relation to the rest of the EZ. This situation is not sustainable. The large German surplus is a symptom of that situation.

Under flexible exchange rates, the German currency would have been able to appreciate against the other EZ countries, eliminating the competitive advantage. In a currency union, the only feasible outcome is for German inflation to run ahead of the rest of the EZ by a significant and persistent amount for a number of years. If the ECB was willing and able to target 2% inflation, then that would mean future German inflation significantly and persistently above 2%. That would require excess demand in Germany, to balance deficient demand in the rest of the EZ. There is really no way around this consequence of a 2% inflation target - it is just arithmetic.

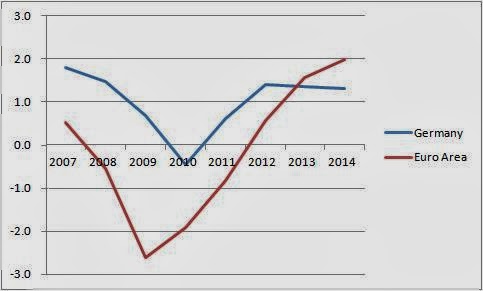

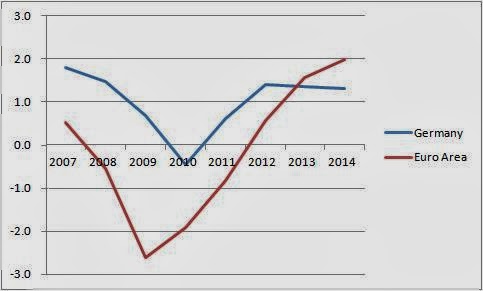

The problem arises because the ECB is unwilling or unable to target 2% inflation. That in theory allows Germany to attempt to force the EZ as a whole to make the required internal adjustment without inflation in Germany exceeding 2%. It can do this by a restrictive fiscal policy. This is exactly what it has done. The figure below shows the underlying primary financial balance in Germany and the whole EZ (including Germany). (Source: Oct 2013 OECD Economic Outlook.) The projected German surpluses are expected to bring down the debt to GDP ratio from 51% of GDP in 2012 to 48.5% of GDP in 2014.

Other EZ countries are defenseless against this deflation, because of imposed austerity or the EZ Fiscal Compact. As a result, the path we seem to be on involves German inflation at around 2% and average EZ inflation well below 2%. This may be in Germany’s narrow national interest, but for the EZ as a whole it is much more costly, partly because of the difficulties of reducing inflation when it is close to zero. Deflation in the EZ as a whole is also costly for those outside the EZ when everyone’s interest rates are near zero (see Francesco Saraceno here)."

http://mainlymacro.blogspot.co.uk/2013/11/the-view-from-germany.html

Charges of Hypocrisy

Hypocrisy has been alleged on multiple bases. "Germany is coming across like a know-it-all in the debate over aid for Greece", commented Der Spiegel, while its own government did not achieve a budget surplus during the era of 1970 to 2011

although a budget surplus indeed was achieved by Germany in all three subsequent years (2012–2014)[130] – with a spokesman for the governing CDU party commenting that "Germany is leading by example in the eurozone – only spending money in its coffers". A Bloomberg editorial, which also concluded that "Europe's taxpayers have provided as much financial support to Germany as they have to Greece", stated the German role and posture in the Greek crisis thus:

---

In the millions of words written about Europe's debt crisis, Germany is typically cast as the responsible adult and Greece as the profligate child. Prudent Germany, the narrative goes, is loath to bail out freeloading Greece, which borrowed more than it could afford and now must suffer the consequences. [...] By December 2009, according to the Bank for International Settlements, German banks had amassed claims of $704 billion on Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain, much more than the German banks' aggregate capital. In other words, they lent more than they could afford. [… I]rresponsible borrowers can't exist without irresponsible lenders. Germany's banks were Greece's enablers.[259 .. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/apr/19/greece-military-spending-debt-crisis ]

---

German economic historian Albrecht Ritschl describes his country as "king when it comes to debt. Calculated based on the amount of losses compared to economic performance, Germany was the biggest debt transgressor of the 20th century."[256 .. http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/economic-historian-germany-was-biggest-debt-transgressor-of-20th-century-a-769703.html ] Despite calling for the Greeks to adhere to fiscal responsibility, and although Germany's tax revenues are at a record high, with the interest it has to pay on new debt at close to zero, Germany still missed its own cost-cutting targets in 2011 and is also falling behind on its goals for 2012. There have been widespread accusations that Greeks are lazy[by whom?], but analysis of OECD data shows that the average Greek worker puts in 50% more hours per year than a typical German counterpart,[261] and the average retirement age of a Greek is, at 61.7 years, older than that of a German. US economist Mark Weisbrot has also noted that while the eurozone giant's post-crisis recovery has been touted as an example of an economy of a country that "made the short-term sacrifices necessary for long-term success", Germany did not apply to its economy the harsh pro-cyclical austerity measures that are being imposed on countries like Greece, In addition, he noted that Germany did not lay off hundreds of thousands of its workers despite a decline in output in its economy but reduced the number of working hours to keep them employed, at the same time as Greece and other countries were pressured to adopt measures to make it easier for employers to lay off workers.[263 .. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cifamerica/2010/aug/27/useconomy-useconomicgrowth ] Weisbrot concludes that the German recovery provides no evidence that the problems created by the use of a single currency in the eurozone can be solved by imposing "self-destructive" pro-cyclical policies as has been done in Greece and elsewhere. Arms sales are another fountainhead for allegations of hypocrisy. Dimitris Papadimoulis, a Greek MP with the Coalition of the Radical Left party:

---

If there is one country that has benefited from the huge amounts Greece spends on defence it is Germany. Just under 15% of Germany's total arms exports are made to Greece, its biggest market in Europe. Greece has paid over €2bn for submarines that proved to be faulty and which it doesn't even need. It owes another €1bn as part of the deal. That's three times the amount Athens was asked to make in additional pension cuts to secure its latest EU aid package. […] Well after the economic crisis had begun, Germany and France were trying to seal lucrative weapons deals even as they were pushing us to make deep cuts in areas like health. […] There's a level of hypocrisy here that is hard to miss. Corruption in Greece is frequently singled out as a cause for waste but at the same time companies like Ferrostaal and Siemens are pioneers in the practice. A big part of our defence spending is bound up with bribes, black money that funds the [mainstream] political class in a nation where governments have got away with it by long playing on peoples' fears.[265]

---

Thus allegations of hypocrisy could be made towards both sides: Germany complains of Greek corruption, yet the murky arms sales meant that the trade with Greece became synonymous with high-level bribery and corruption; former defence minister Akis Tsochadzopoulos was gaoled in April 2012 ahead of his trial on charges of accepting an €8m bribe from Germany company Ferrostaal. In 2000, the current German finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, was forced to resign after personally accepting a "donation" (100,000 Deutsche Mark, in cash) from a fugitive weapons dealer, Karlheinz Schreiber.

Another is German complaints about tax evasion by moneyed Greeks. Germans stashing cash in Switzerland to avoid tax could sleep easy" after summer 2011, when "the German government […] initialled a beggar-thy-neighbour deal that undermine[d] years of diplomatic work to penetrate Switzerland's globally corrosive banking secrecy." Nevertheless, Germans with Swiss bank accounts are so worried, and so intent on avoiding paying tax, that some have taken to cross-dressing, wearing incontinence diapers, and other ruses to try and smuggle their money over the Swiss–German border and so avoid paying their dues to the German taxman. Aside from these unusual techniques to avoid paying tax, Germans have a history of partaking in massive tax evasion: a 1993 ZEW estimate of levels of income-tax avoidance in West Germany in the early 1980s was forced to conclude that "tax loss [in the FDR] exceeds estimates for other countries by orders of magnitude." (The study even excluded the wealthiest 2% of the population, where tax evasion is at its worst). A 2011 study noted that, since the 1990s, the "effective average tax rates for the German super rich have fallen by about a third, with major reductions occurring in the wake of the personal income tax reform of 2001–2005."

Alleged pursuit of national self-interest

Since the euro came into circulation in 2002—a time when the country was suffering slow growth and high unemployment—Germany's export performance, coupled with sustained pressure for moderate wage increases (German wages increased more slowly than those of any other eurozone nation) and rapidly rising wage increases elsewhere, provided its exporters with a competitive advantage that resulted in German domination of trade and capital flows within the currency bloc. As noted by Paul De Grauwe in his leading text on monetary union, however, one must "hav[e] homogenous preferences about inflation in order to have a smoothly functioning monetary union." Thus, as the Levy Economics Institute put it, in jettisoning a common inflation rate, Germany "broke the golden rule of a monetary union".[274 .. http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_721.pdf ] The violation of this golden rule led to dire imbalances within the eurozone, though they suited Germany well: the country's total export trade value nearly tripled between 2000 and 2007, and though a significant proportion of this is accounted for by trade with China, Germany's trade surplus with the rest of the EU grew from €46.4 bn to €126.5 bn during those seven years. Germany's bilateral trade surpluses with the peripheral countries are especially revealing: between 2000 and 2007, Greece's annual trade deficit with Germany nearly doubled, from €3 bn to €5.5 bn; Italy's more than doubled, from €9.6 bn to €19.6 bn; Spain's well over doubled, from €11 bn to €27.2 bn; and Portugal's more than quadrupled, from €1 bn to €4.2 bn. German banks played an important role in supplying the credit that drove wage increases in peripheral eurozone countries like Greece, which in turn produced this divergence in competitiveness and trade surpluses between Germany and these same eurozone members:

---

There is ample evidence that, in the last ten years, the largest wage increases took place in countries like Spain or Greece that experienced the strongest domestic demand growth. Thus demand drives wages and not the other way round, since the PIGS suffered from the bulk of the loss of competitiveness after unemployment in these countries had fallen sharply. The statistical loss of competitiveness of the PIGS thus should not be traced back to inadequate reforms or aggressive trade unions, but instead to booms in domestic demand. The latter has been driven above all by cheap credit for consumption purposes in the case of Greece and for construction work in the cases of Spain and Ireland. This, in turn, translated into higher labor demand and, as a consequence, also to higher wages[276 .. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/41330832?sid=21105833622833&uid=2&uid=3739560&uid=3739256&uid=4 ]

---

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman remarked:

---

Listen to many European leaders—especially, but by no means only, the Germans—and you'd think that their continent's troubles are a simple morality tale of debt and punishment: Governments borrowed too much, now they're paying the price, and fiscal austerity is the only answer.[277 .. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/12/opinion/an-impeccable-disaster.html ]

---

Germans see their government finances and trade competitiveness as an example to be followed by Greece, Portugal and other troubled countries in Europe, but the problem is more than simply a question of southern European countries emulating Germany. Dealing with debt via domestic austerity and a move toward trade surpluses is very difficult without the option of devaluing your currency, and Greece cannot devalue because it is chained to the euro. Roberto Perotti of Bocconi University has also shown that on the rare occasions when austerity and expansion coincide, the coincidence is almost always attributable to rising exports associated with currency depreciation. As can be seen from the case of China and the US, however, where China has had the yuan pegged to the dollar, it is possible to have an effective devaluation in situations where formal devaluation cannot occur, and that is by having the inflation rates of two countries diverge. If German inflation rises faster than that of Greece and other strugglers, then the real effective exchange rate will move in the strugglers' favour despite the shared currency. Trade between the two can then rebalance, aiding recovery, as Greece's products become cheaper.[280] Dean Baker therefore argued that the problem is Germany continuing to shut off just such an adjustment mechanism, meaning

[its] position on the heavily indebted southern countries is absurd. It wants to maintain its huge trade surplus with these countries, while still insisting that they make good on their debts. This is like a store owner insisting that his customers keep buying more from him, while still paying off their debts.[279 .. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/germanys-qsuccessq-and-southern-europes-failure ]

"The counterpart to Germany living within its means is that others are living beyond their means", agreed Philip Whyte, senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform. "So if Germany is worried about the fact that other countries are sinking further into debt, it should be worried about the size of its trade surpluses, but it isn't."[284]

[ i'll leave all reference numbers in from now ]

Germany, though not the worst offender, has even been ringing up arms sales to Greece in the order of tens of millions of euros,[285] and has "recruited thousands of the Continent's best and brightest […] a migration of highly qualified young job-seekers that could set back Europe's stragglers even more, while giving Germany a further leg up",[286] the latter fact openly acknowledged by the new German foreign minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier.[287]

[ of course that 'selfish' situation whereby stronger countries take so much of the cream of a weaker countries expertise is a 'problem' worldwide ]

OECD projections of relative export prices—a measure of competitiveness—showed Germany beating all euro zone members except for crisis-hit Spain and Ireland for 2012, with the lead only widening in subsequent years.[288] A study by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 2010 noted that "Germany, now poised to derive the greatest gains from the euro's crisis-triggered decline, should boost its domestic demand" to help the periphery recover.[289] In March 2012, Bernhard Speyer of Deutsche Bank reiterated: "If the eurozone is to adjust, southern countries must be able to run trade surpluses, and that means somebody else must run deficits. One way to do that is to allow higher inflation in Germany but I don't see any willingness in the German government to tolerate that, or to accept a current account deficit."[290] (A year later, Germany continued to reject pleas for it to run deficits).[291] A research paper by Credit Suisse concurred: "Solving the periphery economic imbalances does not only rest on the periphery countries' shoulders even if these countries have been asked to bear most of the burden. Part of the effort to re-balance Europe also has to been borne by Germany via its current account."[292] At the end of May 2012, the European Commission warned that an "orderly unwinding of intra-euro area macroeconomic imbalances is crucial for sustainable growth and stability in the euro area," and prodded Germany to "contribute to rebalancing by removing unnecessary regulatory and other constraints on domestic demand".[293] In July 2012, the IMF added its call for higher wages and prices in Germany, and for reform of parts of the country's economy to encourage more spending by its consumers (which would help generate demand that would soak up exports from other countries), saying such adjustments were "pivotal" to rebalancing the eurozone and global economy.[294] In October 2012, even Christine Lagarde called for Greece to at least be given more time to meet bailout targets, though this was immediately rejected by Germany's finance minister.[295] As if to emphasise the root problem, when downgrading France and other eurozone countries in January 2012, S&P gave one of its reasons as "divergences in competitiveness between the eurozone's core and the so-called 'periphery'".[296] The Germans "wear their anti-inflation obsession as a badge of honour",[278] but "price stability for Germany [… means] catastrophe for the euro."[297] Paul Krugman estimates that Spain and other peripherals need to reduce their price levels relative to Germany by around 20 percent to become competitive again:

---

If Germany had 4 percent inflation, they could do that over 5 years with stable prices in the periphery—which would imply an overall eurozone inflation rate of something like 3 percent. But if Germany is going to have only 1 percent inflation, we're talking about massive deflation in the periphery, which is both hard (probably impossible) as a macroeconomic proposition, and would greatly magnify the debt burden. This is a recipe for failure, and collapse.[297 .. http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/25/catastrophic-stability/ ]

---

The US has also repeatedly, and heatedly, asked Germany to loosen fiscal policy at G7 meetings, but the Germans have repeatedly refused.[298][299] The US Treasury Department's semi-annual currency report for October 2013 observed that:

---

Within the euro area, countries with large and persistent surpluses need to take action to boost domestic demand growth and shrink their surpluses. Germany has maintained a large current account surplus throughout the euro area financial crisis, and in 2012, Germany's nominal current account surplus was larger than that of China. Germany's anemic pace of domestic demand growth and dependence on exports have hampered rebalancing at a time when many other euro-area countries have been under severe pressure to curb demand and compress imports in order to promote adjustment. The net result has been a deflationary bias for the euro area, as well as for the world economy. […] Stronger domestic demand growth in surplus European economies, particularly in Germany, would help to facilitate a durable rebalancing of imbalances in the euro area.[300]

---

These October 2013 Treasury Department observations would germinate in the very poorest of soil, however, because the year before, in October 2012, Germany had chosen to legally cement its dismissal of these repeated pleas by legislating against the very possibility of stimulus spending, "by passing a balanced budget law that requires the government to run near-zero structural deficits indefinitely."[301] November 2013 saw the European Commission open an in-depth inquiry into German's surplus.[302]

Even with such policies, Greece and other countries would face years of hard times, but at least there would be some hope of recovery.[303] By May 2012, there were signs that the status quo, and "it's tough to overstate just how fantastic the status quo has been for Germany", was beginning to change as even France began to challenge German policy,[304][305] and in April 2013, a week after even Manuel Barroso had warned that austerity had "reached its limits",[306] EU employment chief Laszlo Andor called for a radical change in EU crisis strategy—"If there is no growth, I don't see how countries can cut their debt levels"—and criticised what he described as the German practice of "wage dumping" within the eurozone to gain larger export surpluses.[305] "The euro has allowed Germany to 'beggar its neighbours', while also providing the mechanisms and the ideology for imposing austerity on the continent", announced Heiner Flassbeck (a former German vice finance minister) and economist Costas Lapavitsas in 2013,[307] not long after a leaked version of a text from French president Francois Hollande's Socialist Party openly attacked "German austerity" and the "egoistic intransigence of Mrs Merkel".[305] 2012 saw the German trade surplus rise to second highest level since 1950,[308] but 2013 saw continuing signs that the crisis was gradually taking its toll.[309]

Battered by criticism,[310] the European Commission finally decided that "something more" was needed in addition to austerity policies for peripheral countries like Greece. "Something more" was announced to be structural reforms—things like making it easier for companies to sack workers—but such reforms have been there from the very beginning, leading Dani Rodrik to dismiss the EC's idea as "merely old wine in a new bottle." Indeed, Rodrik noted that with demand gutted by austerity, all structural reforms have achieved, and would continue to achieve, is pumping up unemployment (further reducing demand), since fired workers are not going to be re-employed elsewhere. Rodrik suggested the ECB might like to try out a higher inflation target, and that Germany might like to allow increased demand, higher inflation, and to accept its banks taking losses on their reckless lending to Greece. That, however, "assumes that Germans can embrace a different narrative about the nature of the crisis. And that means that German leaders must portray the crisis not as a morality play pitting lazy, profligate southerners against hard-working, frugal northerners, but as a crisis of interdependence in an economic (and nascent political) union. Germans must play as big a role in resolving the crisis as they did in instigating it."[311] Paul Krugman described talk of structural reform as "an excuse for not facing up to the reality of macroeconomic disaster, and a way to avoid discussing the responsibility of Germany and the ECB, in particular, to help end this disaster."[312] Furthermore, Financial Times analyst Wolfgang Munchau observed that

---

Austerity and reform are the opposite of each other. If you are serious about structural reform, it will cost you upfront money. [… A]usterity […] weaken[s] the economy's capacity in the short run, and possibly also in the long run. If you have youth unemployment of more than 50 per cent for a sustained period, as is now the case in Greece, […] many of those people will never find good jobs in their lives.[313]

---

Though Germany claims its public finances are "the envy of the world",[314] the country is merely continuing what has been called its "free-riding" of the euro crisis, which "consists in using the euro as a mechanism for maintaining a weak exchange rate while shifting the costs of doing so to its neighbors."[315] The weakness of the euro, caused by the economy misery of peripheral countries, has been providing Germany with a large and artificial export advantage to the extent that, if Germany left the euro, the concomitant surge in the value of the reintroduced Deutsche Mark, which would produce "disastrous"[316] effects on German exports as they suddenly became dramatically more expensive, would play the lead role in imposing a cost on Germany of perhaps 20–25% GDP during the first year alone after its euro exit.[317] Claims that Germany had, by mid-2012, given Greece the equivalent of 29 times the aid given to West Germany under the Marshall Plan after World War II completely ignores the fact that aid was just a small part of Marshall Plan assistance to Germany, with another crucial part of the assistance being the writing off of a majority of Germany's debt.[318]

Germany insists that it is ready to do "everything" to guarantee the eurozone.[319] "Yet, for all the rhetoric, little has changed. The austerity strategy imposed by Berlin on Europe's 'Arc of Depression'—against the better judgement of the European Commission, the OECD, International Monetary Fund, and informed economic opinion across the globe—has not been modified in the slightest even though economic contraction has proved deeper than expected in every single victim country."[319] The version of adjustment offered by Germany and its allies is that austerity will lead to an internal devaluation, i.e. deflation, which would enable Greece gradually to regain competitiveness. "Yet this proposed solution is a complete non-starter", in the opinion of one UK economist. "If austerity succeeds in delivering deflation, then the growth of nominal GDP will be depressed; most likely it will turn negative. In that case, the burden of debt will increase."[320] A February 2013 research note by the Economics Research team at Goldman Sachs again noted that the years of recession being endured by Greece "exacerbate the fiscal difficulties as the denominator of the debt-to-GDP ratio diminishes",[321] i.e. reducing the debt burden by imposing austerity is, aside from anything else, utterly futile.[322][323] "Higher growth has always been the best way out the debt (absolute and relative) burden. However, growth prospects for the near and medium-term future are quite weak. During the Great Depression, Heinrich Brüning, the German Chancellor (1930–32), thought that a strong currency and a balanced budget were the ways out of crisis. Cruel austerity measures such as cuts in wages, pensions and social benefits followed. Over the years crises deepened".[324] The austerity program applied to Greece has been "self-defeating",[325] with the country's debt now expected to balloon to 192% of GDP by 2014.[326] After years of the situation being pointed out, in June 2013, with the Greek debt burden galloping towards the "staggering"[327] heights previously predicted by anyone who knew what they were talking about, and with her own organization admitting its program for Greece had failed seriously on multiple primary objectives[328] and that it had bent its rules when "rescuing" Greece;[329] and having claimed in the past that Greece's debt was sustainable[329]—Christine Lagarde felt able to admit publicly that perhaps Greece just might, after all, need to have its debt written off in a meaningful way.[327] In its Global Economic Outlook and Strategy of September 2013, Citi pointed out that Greece "lack[s] the ability to stabilise […] debt/GDP ratios in coming years by fiscal policy alone",[330]:7 and that "large debt relief" is probably "the only viable option" if Greek fiscal sustainability is to re-materialise;[330]:18 predicted no return to growth until 2016;[330]:8 and predicted that the debt burden would soar to over 200% of GDP by 2015 and carry on rising through at least 2017.[330]:9 Unfortunately, German Chancellor Merkel and Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle had just a few months prior already spoken out again against any debt relief for Greece, claiming that "structural reforms" (i.e. "old wine in a new bottle", see Rodrik et al. above) were the way to go and—astonishingly—that "debt sustainability will continue to be assured".[331][332]

Strictly in terms of reducing wages relative to Germany, Greece had been making 'progress': private-sector wages fell 5.4% in the third quarter of 2011 from a year earlier and 12% since their peak in the first quarter of 2010.[333] The second economic adjustment programme for Greece called for a further labour cost reduction in the private sector of 15% during 2012–2014.[334]

The question then is whether Germany would accept the price of inflation for the benefit of keeping the eurozone together.[335] On the upside, inflation, at least to start with, would make Germans happy as their wages rose in keeping with inflation.[335] Regardless of these positives, as soon as the monetary policy of the ECB—which has been catering to German desires for low inflation[336][337] so doggedly that Martin Wolf describes it as "a reincarnated Bundesbank"[338]—began to look like it might stoke inflation in Germany, Merkel moved to counteract, cementing the impossibility of a recovery for struggling countries.[290] With eurozone adjustment locked out by Germany, economic hardship elsewhere in the currency block actually suited its export-oriented economy for an extended period, because it caused the euro to depreciate,[339] making German exports cheaper and so more competitive.[278][340] By July 2012, however, the European crisis was beginning to take its toll.[341] Germany's unemployment continued its downward trend to record lows in March 2012,[342] and yields on its government bonds fell to repeat record lows in the first half of 2012 (though real interest rates are actually negative).[343][344]

German and other financial institutions have scooped a huge chunk of the rescue package: "more than 80 percent of the rescue package is going to creditors—that is to say, to banks outside of Greece and to the ECB. The billions of taxpayer euros are not saving Greece. They're saving the banks."[345] The shift in liabilities from European banks to European taxpayers has been staggering: one study found that the public debt of Greece to foreign governments, including debt to the EU/IMF loan facility and debt through the eurosystem, increased by €130 bn, from €47.8 bn to €180.5 billion, between January 2010 and September 2011.[346] The combined exposure of foreign banks to Greek entities—public and private—was around 80bn euros by mid-February 2012. In 2009 they were in for well over 200bn.[347] The Economist noted that, during 2012 alone, "private-sector bondholders reduced their nominal claims by more than 50%. But the deal did not include the hefty holdings of Greek bonds at the European Central Bank (ECB), and it was sweetened with funds borrowed from official rescuers. For two years those rescuers had pretended Greece was solvent, and provided official loans to pay off bondholders in full. So more than 70% of the debts are now owed to 'official' creditors", i.e. European taxpayers and the IMF.[348] With regard to Germany in particular, a Bloomberg editorial noted that, before its banks reduced its exposure to Greece, "they stood to lose a ton of money if Greece left the euro. Now any losses will be shared with the taxpayers of the entire euro area."[259] Similarly in Spain:

---

German lenders will be among the biggest beneficiaries of a Spanish bank bailout, with rescue funds helping to ensure they get paid back in full for poor lending decisions made in the run-up to the financial crisis, and helping politicians in Berlin avoid a politically sensitive bank bailout of their own. German lenders were among Europe's most profligate before 2008, channelling the country's savings to the European periphery in search of higher profits. […] German banks were facing deep losses linked to potential Spanish bank failures. However, a bailout of Spanish banks—backed initially by Spanish taxpayers and potentially later by the European Stability Mechanism—will ensure creditors won't take losses, making the bailout effectively a back-door bailout of reckless German lending. […] Jens Sondergaard, senior European economist at Nomura, said: "The Spanish bailout in effect is a bailout of German banks. If lenders in Spain were allowed to default, the consequences for the German banking system would be very serious."[349 .. http://in.reuters.com/article/2012/06/29/spain-germany-bailout-ifr-idINL6E8HTFC820120629 ]

---

The director of LSE's Hellenic Observatory mused: "Who is rescued by the bailouts of the European debt crisis? The question won't go away. […] The Greek banks—vital to the provision of new investment in an economy facing a sixth year of continuous recession—have certainly not been 'rescued' [… and] face large-scale nationalisation. […] Athenians might well turn the aphorism around and warn their partners in Lisbon: 'Beware of Europeans bearing gifts.'"[350]

All of this has resulted in increased anti-German sentiment within peripheral countries like Greece and Spain.[351][352][353] German historian Arnulf Baring, who opposed the euro, wrote in his 1997 book Scheitert Deutschland? (Does Germany fail?): "They (populistic media and politicians) will say that we finance lazy slackers, sitting in coffee shops on southern beaches", and "[t]he fiscal union will end in a giant blackmail manoeuvre […] When we Germans will demand fiscal discipline, other countries will blame this fiscal discipline and therefore us for their financial difficulties. Besides, although they initially agreed on the terms, they will consider us as some kind of economic police. Consequently, we risk again becoming the most hated people in Europe."[354] Anti-German animus is perhaps inflamed by the fact that, as one German historian noted, "during much of the 20th century, the situation was radically different: after the first world war and again after the second world war, Germany was the world's largest debtor, and in both cases owed its economic recovery to large-scale debt relief."[355] When Horst Reichenbach arrived in Athens towards the end of 2011 to head a new European Union task force, the Greek media instantly dubbed him "Third Reichenbach";[284] in Spain in May 2012, businessmen made unflattering comparisons with Berlin's domination of Europe in WWII, and top officials "mutter about how today's European Union consists of a 'German Union plus the rest'".[352] Almost four million German tourists—more than any other EU country—visit Greece annually, but they comprised most of the 50,000 cancelled bookings in the ten days after the 6 May 2012 Greek elections, a figure The Observer called "extraordinary". The Association of Greek Tourism Enterprises estimates that German visits for 2012 will decrease by about 25%.[356] Such is the ill-feeling, historic claims on Germany from WWII have been reopened,[357] including "a huge, never-repaid loan the nation was forced to make under Nazi occupation from 1941 to 1945."[358]

Hedge funds - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_government-debt_crisis

1. German banks lent the most to Greece.

2. Germany has refused to be fiscally responsible toward the weaker economies of the eurozone.

3. Germany enjoyed "falling borrowing rates, investment influx, and exports boost thanks to Euro’s depreciation

"Germans claim this is mostly due to painful reforms over the past decade that turned the former sick man of Europe into its most competitive economy. But also important have been a weak currency, near-record-low borrowing costs and the willingness of its European neighbors to keep buying German goods—often with money effectively borrowed from Germany. Truly, it's an ill wind that blows no one any good.

On that basis, it's hard to dispute that the euro-zone bailout programs have so far proved remarkably good value for Germany."

.. 2011 WSJ .. http://www.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304803104576427971253989738

4. Germany has use the ECB to benefit itself rather to support the weaker economies (today) of the eurozone.

Some of above and all of below, with a couple of added inserts from links supplied, is verbatim here .. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_government-debt_crisis

"From 2000 to 2007, the periphery of the Eurozone (EZ) enjoyed a boom, while Germany did not. As a result, inflation in the periphery (and much else) of the EZ exceeded inflation in Germany by a significant and persistent amount. By 2007, this meant that Germany had become too competitive in relation to the rest of the EZ. This situation is not sustainable. The large German surplus is a symptom of that situation.

Under flexible exchange rates, the German currency would have been able to appreciate against the other EZ countries, eliminating the competitive advantage. In a currency union, the only feasible outcome is for German inflation to run ahead of the rest of the EZ by a significant and persistent amount for a number of years. If the ECB was willing and able to target 2% inflation, then that would mean future German inflation significantly and persistently above 2%. That would require excess demand in Germany, to balance deficient demand in the rest of the EZ. There is really no way around this consequence of a 2% inflation target - it is just arithmetic.

The problem arises because the ECB is unwilling or unable to target 2% inflation. That in theory allows Germany to attempt to force the EZ as a whole to make the required internal adjustment without inflation in Germany exceeding 2%. It can do this by a restrictive fiscal policy. This is exactly what it has done. The figure below shows the underlying primary financial balance in Germany and the whole EZ (including Germany). (Source: Oct 2013 OECD Economic Outlook.) The projected German surpluses are expected to bring down the debt to GDP ratio from 51% of GDP in 2012 to 48.5% of GDP in 2014.

Other EZ countries are defenseless against this deflation, because of imposed austerity or the EZ Fiscal Compact. As a result, the path we seem to be on involves German inflation at around 2% and average EZ inflation well below 2%. This may be in Germany’s narrow national interest, but for the EZ as a whole it is much more costly, partly because of the difficulties of reducing inflation when it is close to zero. Deflation in the EZ as a whole is also costly for those outside the EZ when everyone’s interest rates are near zero (see Francesco Saraceno here)."

http://mainlymacro.blogspot.co.uk/2013/11/the-view-from-germany.html

Charges of Hypocrisy

Hypocrisy has been alleged on multiple bases. "Germany is coming across like a know-it-all in the debate over aid for Greece", commented Der Spiegel, while its own government did not achieve a budget surplus during the era of 1970 to 2011

although a budget surplus indeed was achieved by Germany in all three subsequent years (2012–2014)[130] – with a spokesman for the governing CDU party commenting that "Germany is leading by example in the eurozone – only spending money in its coffers". A Bloomberg editorial, which also concluded that "Europe's taxpayers have provided as much financial support to Germany as they have to Greece", stated the German role and posture in the Greek crisis thus:

---

In the millions of words written about Europe's debt crisis, Germany is typically cast as the responsible adult and Greece as the profligate child. Prudent Germany, the narrative goes, is loath to bail out freeloading Greece, which borrowed more than it could afford and now must suffer the consequences. [...] By December 2009, according to the Bank for International Settlements, German banks had amassed claims of $704 billion on Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain, much more than the German banks' aggregate capital. In other words, they lent more than they could afford. [… I]rresponsible borrowers can't exist without irresponsible lenders. Germany's banks were Greece's enablers.[259 .. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/apr/19/greece-military-spending-debt-crisis ]

---

German economic historian Albrecht Ritschl describes his country as "king when it comes to debt. Calculated based on the amount of losses compared to economic performance, Germany was the biggest debt transgressor of the 20th century."[256 .. http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/economic-historian-germany-was-biggest-debt-transgressor-of-20th-century-a-769703.html ] Despite calling for the Greeks to adhere to fiscal responsibility, and although Germany's tax revenues are at a record high, with the interest it has to pay on new debt at close to zero, Germany still missed its own cost-cutting targets in 2011 and is also falling behind on its goals for 2012. There have been widespread accusations that Greeks are lazy[by whom?], but analysis of OECD data shows that the average Greek worker puts in 50% more hours per year than a typical German counterpart,[261] and the average retirement age of a Greek is, at 61.7 years, older than that of a German. US economist Mark Weisbrot has also noted that while the eurozone giant's post-crisis recovery has been touted as an example of an economy of a country that "made the short-term sacrifices necessary for long-term success", Germany did not apply to its economy the harsh pro-cyclical austerity measures that are being imposed on countries like Greece, In addition, he noted that Germany did not lay off hundreds of thousands of its workers despite a decline in output in its economy but reduced the number of working hours to keep them employed, at the same time as Greece and other countries were pressured to adopt measures to make it easier for employers to lay off workers.[263 .. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cifamerica/2010/aug/27/useconomy-useconomicgrowth ] Weisbrot concludes that the German recovery provides no evidence that the problems created by the use of a single currency in the eurozone can be solved by imposing "self-destructive" pro-cyclical policies as has been done in Greece and elsewhere. Arms sales are another fountainhead for allegations of hypocrisy. Dimitris Papadimoulis, a Greek MP with the Coalition of the Radical Left party:

---

If there is one country that has benefited from the huge amounts Greece spends on defence it is Germany. Just under 15% of Germany's total arms exports are made to Greece, its biggest market in Europe. Greece has paid over €2bn for submarines that proved to be faulty and which it doesn't even need. It owes another €1bn as part of the deal. That's three times the amount Athens was asked to make in additional pension cuts to secure its latest EU aid package. […] Well after the economic crisis had begun, Germany and France were trying to seal lucrative weapons deals even as they were pushing us to make deep cuts in areas like health. […] There's a level of hypocrisy here that is hard to miss. Corruption in Greece is frequently singled out as a cause for waste but at the same time companies like Ferrostaal and Siemens are pioneers in the practice. A big part of our defence spending is bound up with bribes, black money that funds the [mainstream] political class in a nation where governments have got away with it by long playing on peoples' fears.[265]

---

Thus allegations of hypocrisy could be made towards both sides: Germany complains of Greek corruption, yet the murky arms sales meant that the trade with Greece became synonymous with high-level bribery and corruption; former defence minister Akis Tsochadzopoulos was gaoled in April 2012 ahead of his trial on charges of accepting an €8m bribe from Germany company Ferrostaal. In 2000, the current German finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, was forced to resign after personally accepting a "donation" (100,000 Deutsche Mark, in cash) from a fugitive weapons dealer, Karlheinz Schreiber.

Another is German complaints about tax evasion by moneyed Greeks. Germans stashing cash in Switzerland to avoid tax could sleep easy" after summer 2011, when "the German government […] initialled a beggar-thy-neighbour deal that undermine[d] years of diplomatic work to penetrate Switzerland's globally corrosive banking secrecy." Nevertheless, Germans with Swiss bank accounts are so worried, and so intent on avoiding paying tax, that some have taken to cross-dressing, wearing incontinence diapers, and other ruses to try and smuggle their money over the Swiss–German border and so avoid paying their dues to the German taxman. Aside from these unusual techniques to avoid paying tax, Germans have a history of partaking in massive tax evasion: a 1993 ZEW estimate of levels of income-tax avoidance in West Germany in the early 1980s was forced to conclude that "tax loss [in the FDR] exceeds estimates for other countries by orders of magnitude." (The study even excluded the wealthiest 2% of the population, where tax evasion is at its worst). A 2011 study noted that, since the 1990s, the "effective average tax rates for the German super rich have fallen by about a third, with major reductions occurring in the wake of the personal income tax reform of 2001–2005."

Alleged pursuit of national self-interest

Since the euro came into circulation in 2002—a time when the country was suffering slow growth and high unemployment—Germany's export performance, coupled with sustained pressure for moderate wage increases (German wages increased more slowly than those of any other eurozone nation) and rapidly rising wage increases elsewhere, provided its exporters with a competitive advantage that resulted in German domination of trade and capital flows within the currency bloc. As noted by Paul De Grauwe in his leading text on monetary union, however, one must "hav[e] homogenous preferences about inflation in order to have a smoothly functioning monetary union." Thus, as the Levy Economics Institute put it, in jettisoning a common inflation rate, Germany "broke the golden rule of a monetary union".[274 .. http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_721.pdf ] The violation of this golden rule led to dire imbalances within the eurozone, though they suited Germany well: the country's total export trade value nearly tripled between 2000 and 2007, and though a significant proportion of this is accounted for by trade with China, Germany's trade surplus with the rest of the EU grew from €46.4 bn to €126.5 bn during those seven years. Germany's bilateral trade surpluses with the peripheral countries are especially revealing: between 2000 and 2007, Greece's annual trade deficit with Germany nearly doubled, from €3 bn to €5.5 bn; Italy's more than doubled, from €9.6 bn to €19.6 bn; Spain's well over doubled, from €11 bn to €27.2 bn; and Portugal's more than quadrupled, from €1 bn to €4.2 bn. German banks played an important role in supplying the credit that drove wage increases in peripheral eurozone countries like Greece, which in turn produced this divergence in competitiveness and trade surpluses between Germany and these same eurozone members:

---

There is ample evidence that, in the last ten years, the largest wage increases took place in countries like Spain or Greece that experienced the strongest domestic demand growth. Thus demand drives wages and not the other way round, since the PIGS suffered from the bulk of the loss of competitiveness after unemployment in these countries had fallen sharply. The statistical loss of competitiveness of the PIGS thus should not be traced back to inadequate reforms or aggressive trade unions, but instead to booms in domestic demand. The latter has been driven above all by cheap credit for consumption purposes in the case of Greece and for construction work in the cases of Spain and Ireland. This, in turn, translated into higher labor demand and, as a consequence, also to higher wages[276 .. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/41330832?sid=21105833622833&uid=2&uid=3739560&uid=3739256&uid=4 ]

---

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman remarked:

---

Listen to many European leaders—especially, but by no means only, the Germans—and you'd think that their continent's troubles are a simple morality tale of debt and punishment: Governments borrowed too much, now they're paying the price, and fiscal austerity is the only answer.[277 .. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/12/opinion/an-impeccable-disaster.html ]

---

Germans see their government finances and trade competitiveness as an example to be followed by Greece, Portugal and other troubled countries in Europe, but the problem is more than simply a question of southern European countries emulating Germany. Dealing with debt via domestic austerity and a move toward trade surpluses is very difficult without the option of devaluing your currency, and Greece cannot devalue because it is chained to the euro. Roberto Perotti of Bocconi University has also shown that on the rare occasions when austerity and expansion coincide, the coincidence is almost always attributable to rising exports associated with currency depreciation. As can be seen from the case of China and the US, however, where China has had the yuan pegged to the dollar, it is possible to have an effective devaluation in situations where formal devaluation cannot occur, and that is by having the inflation rates of two countries diverge. If German inflation rises faster than that of Greece and other strugglers, then the real effective exchange rate will move in the strugglers' favour despite the shared currency. Trade between the two can then rebalance, aiding recovery, as Greece's products become cheaper.[280] Dean Baker therefore argued that the problem is Germany continuing to shut off just such an adjustment mechanism, meaning

[its] position on the heavily indebted southern countries is absurd. It wants to maintain its huge trade surplus with these countries, while still insisting that they make good on their debts. This is like a store owner insisting that his customers keep buying more from him, while still paying off their debts.[279 .. http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/germanys-qsuccessq-and-southern-europes-failure ]

"The counterpart to Germany living within its means is that others are living beyond their means", agreed Philip Whyte, senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform. "So if Germany is worried about the fact that other countries are sinking further into debt, it should be worried about the size of its trade surpluses, but it isn't."[284]

[ i'll leave all reference numbers in from now ]

Germany, though not the worst offender, has even been ringing up arms sales to Greece in the order of tens of millions of euros,[285] and has "recruited thousands of the Continent's best and brightest […] a migration of highly qualified young job-seekers that could set back Europe's stragglers even more, while giving Germany a further leg up",[286] the latter fact openly acknowledged by the new German foreign minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier.[287]

[ of course that 'selfish' situation whereby stronger countries take so much of the cream of a weaker countries expertise is a 'problem' worldwide ]

OECD projections of relative export prices—a measure of competitiveness—showed Germany beating all euro zone members except for crisis-hit Spain and Ireland for 2012, with the lead only widening in subsequent years.[288] A study by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 2010 noted that "Germany, now poised to derive the greatest gains from the euro's crisis-triggered decline, should boost its domestic demand" to help the periphery recover.[289] In March 2012, Bernhard Speyer of Deutsche Bank reiterated: "If the eurozone is to adjust, southern countries must be able to run trade surpluses, and that means somebody else must run deficits. One way to do that is to allow higher inflation in Germany but I don't see any willingness in the German government to tolerate that, or to accept a current account deficit."[290] (A year later, Germany continued to reject pleas for it to run deficits).[291] A research paper by Credit Suisse concurred: "Solving the periphery economic imbalances does not only rest on the periphery countries' shoulders even if these countries have been asked to bear most of the burden. Part of the effort to re-balance Europe also has to been borne by Germany via its current account."[292] At the end of May 2012, the European Commission warned that an "orderly unwinding of intra-euro area macroeconomic imbalances is crucial for sustainable growth and stability in the euro area," and prodded Germany to "contribute to rebalancing by removing unnecessary regulatory and other constraints on domestic demand".[293] In July 2012, the IMF added its call for higher wages and prices in Germany, and for reform of parts of the country's economy to encourage more spending by its consumers (which would help generate demand that would soak up exports from other countries), saying such adjustments were "pivotal" to rebalancing the eurozone and global economy.[294] In October 2012, even Christine Lagarde called for Greece to at least be given more time to meet bailout targets, though this was immediately rejected by Germany's finance minister.[295] As if to emphasise the root problem, when downgrading France and other eurozone countries in January 2012, S&P gave one of its reasons as "divergences in competitiveness between the eurozone's core and the so-called 'periphery'".[296] The Germans "wear their anti-inflation obsession as a badge of honour",[278] but "price stability for Germany [… means] catastrophe for the euro."[297] Paul Krugman estimates that Spain and other peripherals need to reduce their price levels relative to Germany by around 20 percent to become competitive again:

---

If Germany had 4 percent inflation, they could do that over 5 years with stable prices in the periphery—which would imply an overall eurozone inflation rate of something like 3 percent. But if Germany is going to have only 1 percent inflation, we're talking about massive deflation in the periphery, which is both hard (probably impossible) as a macroeconomic proposition, and would greatly magnify the debt burden. This is a recipe for failure, and collapse.[297 .. http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/25/catastrophic-stability/ ]

---

The US has also repeatedly, and heatedly, asked Germany to loosen fiscal policy at G7 meetings, but the Germans have repeatedly refused.[298][299] The US Treasury Department's semi-annual currency report for October 2013 observed that:

---

Within the euro area, countries with large and persistent surpluses need to take action to boost domestic demand growth and shrink their surpluses. Germany has maintained a large current account surplus throughout the euro area financial crisis, and in 2012, Germany's nominal current account surplus was larger than that of China. Germany's anemic pace of domestic demand growth and dependence on exports have hampered rebalancing at a time when many other euro-area countries have been under severe pressure to curb demand and compress imports in order to promote adjustment. The net result has been a deflationary bias for the euro area, as well as for the world economy. […] Stronger domestic demand growth in surplus European economies, particularly in Germany, would help to facilitate a durable rebalancing of imbalances in the euro area.[300]

---

These October 2013 Treasury Department observations would germinate in the very poorest of soil, however, because the year before, in October 2012, Germany had chosen to legally cement its dismissal of these repeated pleas by legislating against the very possibility of stimulus spending, "by passing a balanced budget law that requires the government to run near-zero structural deficits indefinitely."[301] November 2013 saw the European Commission open an in-depth inquiry into German's surplus.[302]

Even with such policies, Greece and other countries would face years of hard times, but at least there would be some hope of recovery.[303] By May 2012, there were signs that the status quo, and "it's tough to overstate just how fantastic the status quo has been for Germany", was beginning to change as even France began to challenge German policy,[304][305] and in April 2013, a week after even Manuel Barroso had warned that austerity had "reached its limits",[306] EU employment chief Laszlo Andor called for a radical change in EU crisis strategy—"If there is no growth, I don't see how countries can cut their debt levels"—and criticised what he described as the German practice of "wage dumping" within the eurozone to gain larger export surpluses.[305] "The euro has allowed Germany to 'beggar its neighbours', while also providing the mechanisms and the ideology for imposing austerity on the continent", announced Heiner Flassbeck (a former German vice finance minister) and economist Costas Lapavitsas in 2013,[307] not long after a leaked version of a text from French president Francois Hollande's Socialist Party openly attacked "German austerity" and the "egoistic intransigence of Mrs Merkel".[305] 2012 saw the German trade surplus rise to second highest level since 1950,[308] but 2013 saw continuing signs that the crisis was gradually taking its toll.[309]

Battered by criticism,[310] the European Commission finally decided that "something more" was needed in addition to austerity policies for peripheral countries like Greece. "Something more" was announced to be structural reforms—things like making it easier for companies to sack workers—but such reforms have been there from the very beginning, leading Dani Rodrik to dismiss the EC's idea as "merely old wine in a new bottle." Indeed, Rodrik noted that with demand gutted by austerity, all structural reforms have achieved, and would continue to achieve, is pumping up unemployment (further reducing demand), since fired workers are not going to be re-employed elsewhere. Rodrik suggested the ECB might like to try out a higher inflation target, and that Germany might like to allow increased demand, higher inflation, and to accept its banks taking losses on their reckless lending to Greece. That, however, "assumes that Germans can embrace a different narrative about the nature of the crisis. And that means that German leaders must portray the crisis not as a morality play pitting lazy, profligate southerners against hard-working, frugal northerners, but as a crisis of interdependence in an economic (and nascent political) union. Germans must play as big a role in resolving the crisis as they did in instigating it."[311] Paul Krugman described talk of structural reform as "an excuse for not facing up to the reality of macroeconomic disaster, and a way to avoid discussing the responsibility of Germany and the ECB, in particular, to help end this disaster."[312] Furthermore, Financial Times analyst Wolfgang Munchau observed that

---

Austerity and reform are the opposite of each other. If you are serious about structural reform, it will cost you upfront money. [… A]usterity […] weaken[s] the economy's capacity in the short run, and possibly also in the long run. If you have youth unemployment of more than 50 per cent for a sustained period, as is now the case in Greece, […] many of those people will never find good jobs in their lives.[313]

---

Though Germany claims its public finances are "the envy of the world",[314] the country is merely continuing what has been called its "free-riding" of the euro crisis, which "consists in using the euro as a mechanism for maintaining a weak exchange rate while shifting the costs of doing so to its neighbors."[315] The weakness of the euro, caused by the economy misery of peripheral countries, has been providing Germany with a large and artificial export advantage to the extent that, if Germany left the euro, the concomitant surge in the value of the reintroduced Deutsche Mark, which would produce "disastrous"[316] effects on German exports as they suddenly became dramatically more expensive, would play the lead role in imposing a cost on Germany of perhaps 20–25% GDP during the first year alone after its euro exit.[317] Claims that Germany had, by mid-2012, given Greece the equivalent of 29 times the aid given to West Germany under the Marshall Plan after World War II completely ignores the fact that aid was just a small part of Marshall Plan assistance to Germany, with another crucial part of the assistance being the writing off of a majority of Germany's debt.[318]

Germany insists that it is ready to do "everything" to guarantee the eurozone.[319] "Yet, for all the rhetoric, little has changed. The austerity strategy imposed by Berlin on Europe's 'Arc of Depression'—against the better judgement of the European Commission, the OECD, International Monetary Fund, and informed economic opinion across the globe—has not been modified in the slightest even though economic contraction has proved deeper than expected in every single victim country."[319] The version of adjustment offered by Germany and its allies is that austerity will lead to an internal devaluation, i.e. deflation, which would enable Greece gradually to regain competitiveness. "Yet this proposed solution is a complete non-starter", in the opinion of one UK economist. "If austerity succeeds in delivering deflation, then the growth of nominal GDP will be depressed; most likely it will turn negative. In that case, the burden of debt will increase."[320] A February 2013 research note by the Economics Research team at Goldman Sachs again noted that the years of recession being endured by Greece "exacerbate the fiscal difficulties as the denominator of the debt-to-GDP ratio diminishes",[321] i.e. reducing the debt burden by imposing austerity is, aside from anything else, utterly futile.[322][323] "Higher growth has always been the best way out the debt (absolute and relative) burden. However, growth prospects for the near and medium-term future are quite weak. During the Great Depression, Heinrich Brüning, the German Chancellor (1930–32), thought that a strong currency and a balanced budget were the ways out of crisis. Cruel austerity measures such as cuts in wages, pensions and social benefits followed. Over the years crises deepened".[324] The austerity program applied to Greece has been "self-defeating",[325] with the country's debt now expected to balloon to 192% of GDP by 2014.[326] After years of the situation being pointed out, in June 2013, with the Greek debt burden galloping towards the "staggering"[327] heights previously predicted by anyone who knew what they were talking about, and with her own organization admitting its program for Greece had failed seriously on multiple primary objectives[328] and that it had bent its rules when "rescuing" Greece;[329] and having claimed in the past that Greece's debt was sustainable[329]—Christine Lagarde felt able to admit publicly that perhaps Greece just might, after all, need to have its debt written off in a meaningful way.[327] In its Global Economic Outlook and Strategy of September 2013, Citi pointed out that Greece "lack[s] the ability to stabilise […] debt/GDP ratios in coming years by fiscal policy alone",[330]:7 and that "large debt relief" is probably "the only viable option" if Greek fiscal sustainability is to re-materialise;[330]:18 predicted no return to growth until 2016;[330]:8 and predicted that the debt burden would soar to over 200% of GDP by 2015 and carry on rising through at least 2017.[330]:9 Unfortunately, German Chancellor Merkel and Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle had just a few months prior already spoken out again against any debt relief for Greece, claiming that "structural reforms" (i.e. "old wine in a new bottle", see Rodrik et al. above) were the way to go and—astonishingly—that "debt sustainability will continue to be assured".[331][332]

Strictly in terms of reducing wages relative to Germany, Greece had been making 'progress': private-sector wages fell 5.4% in the third quarter of 2011 from a year earlier and 12% since their peak in the first quarter of 2010.[333] The second economic adjustment programme for Greece called for a further labour cost reduction in the private sector of 15% during 2012–2014.[334]

The question then is whether Germany would accept the price of inflation for the benefit of keeping the eurozone together.[335] On the upside, inflation, at least to start with, would make Germans happy as their wages rose in keeping with inflation.[335] Regardless of these positives, as soon as the monetary policy of the ECB—which has been catering to German desires for low inflation[336][337] so doggedly that Martin Wolf describes it as "a reincarnated Bundesbank"[338]—began to look like it might stoke inflation in Germany, Merkel moved to counteract, cementing the impossibility of a recovery for struggling countries.[290] With eurozone adjustment locked out by Germany, economic hardship elsewhere in the currency block actually suited its export-oriented economy for an extended period, because it caused the euro to depreciate,[339] making German exports cheaper and so more competitive.[278][340] By July 2012, however, the European crisis was beginning to take its toll.[341] Germany's unemployment continued its downward trend to record lows in March 2012,[342] and yields on its government bonds fell to repeat record lows in the first half of 2012 (though real interest rates are actually negative).[343][344]

German and other financial institutions have scooped a huge chunk of the rescue package: "more than 80 percent of the rescue package is going to creditors—that is to say, to banks outside of Greece and to the ECB. The billions of taxpayer euros are not saving Greece. They're saving the banks."[345] The shift in liabilities from European banks to European taxpayers has been staggering: one study found that the public debt of Greece to foreign governments, including debt to the EU/IMF loan facility and debt through the eurosystem, increased by €130 bn, from €47.8 bn to €180.5 billion, between January 2010 and September 2011.[346] The combined exposure of foreign banks to Greek entities—public and private—was around 80bn euros by mid-February 2012. In 2009 they were in for well over 200bn.[347] The Economist noted that, during 2012 alone, "private-sector bondholders reduced their nominal claims by more than 50%. But the deal did not include the hefty holdings of Greek bonds at the European Central Bank (ECB), and it was sweetened with funds borrowed from official rescuers. For two years those rescuers had pretended Greece was solvent, and provided official loans to pay off bondholders in full. So more than 70% of the debts are now owed to 'official' creditors", i.e. European taxpayers and the IMF.[348] With regard to Germany in particular, a Bloomberg editorial noted that, before its banks reduced its exposure to Greece, "they stood to lose a ton of money if Greece left the euro. Now any losses will be shared with the taxpayers of the entire euro area."[259] Similarly in Spain:

---

German lenders will be among the biggest beneficiaries of a Spanish bank bailout, with rescue funds helping to ensure they get paid back in full for poor lending decisions made in the run-up to the financial crisis, and helping politicians in Berlin avoid a politically sensitive bank bailout of their own. German lenders were among Europe's most profligate before 2008, channelling the country's savings to the European periphery in search of higher profits. […] German banks were facing deep losses linked to potential Spanish bank failures. However, a bailout of Spanish banks—backed initially by Spanish taxpayers and potentially later by the European Stability Mechanism—will ensure creditors won't take losses, making the bailout effectively a back-door bailout of reckless German lending. […] Jens Sondergaard, senior European economist at Nomura, said: "The Spanish bailout in effect is a bailout of German banks. If lenders in Spain were allowed to default, the consequences for the German banking system would be very serious."[349 .. http://in.reuters.com/article/2012/06/29/spain-germany-bailout-ifr-idINL6E8HTFC820120629 ]

---

The director of LSE's Hellenic Observatory mused: "Who is rescued by the bailouts of the European debt crisis? The question won't go away. […] The Greek banks—vital to the provision of new investment in an economy facing a sixth year of continuous recession—have certainly not been 'rescued' [… and] face large-scale nationalisation. […] Athenians might well turn the aphorism around and warn their partners in Lisbon: 'Beware of Europeans bearing gifts.'"[350]

All of this has resulted in increased anti-German sentiment within peripheral countries like Greece and Spain.[351][352][353] German historian Arnulf Baring, who opposed the euro, wrote in his 1997 book Scheitert Deutschland? (Does Germany fail?): "They (populistic media and politicians) will say that we finance lazy slackers, sitting in coffee shops on southern beaches", and "[t]he fiscal union will end in a giant blackmail manoeuvre […] When we Germans will demand fiscal discipline, other countries will blame this fiscal discipline and therefore us for their financial difficulties. Besides, although they initially agreed on the terms, they will consider us as some kind of economic police. Consequently, we risk again becoming the most hated people in Europe."[354] Anti-German animus is perhaps inflamed by the fact that, as one German historian noted, "during much of the 20th century, the situation was radically different: after the first world war and again after the second world war, Germany was the world's largest debtor, and in both cases owed its economic recovery to large-scale debt relief."[355] When Horst Reichenbach arrived in Athens towards the end of 2011 to head a new European Union task force, the Greek media instantly dubbed him "Third Reichenbach";[284] in Spain in May 2012, businessmen made unflattering comparisons with Berlin's domination of Europe in WWII, and top officials "mutter about how today's European Union consists of a 'German Union plus the rest'".[352] Almost four million German tourists—more than any other EU country—visit Greece annually, but they comprised most of the 50,000 cancelled bookings in the ten days after the 6 May 2012 Greek elections, a figure The Observer called "extraordinary". The Association of Greek Tourism Enterprises estimates that German visits for 2012 will decrease by about 25%.[356] Such is the ill-feeling, historic claims on Germany from WWII have been reopened,[357] including "a huge, never-repaid loan the nation was forced to make under Nazi occupation from 1941 to 1945."[358]

Hedge funds - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_government-debt_crisis

It was Plato who said, “He, O men, is the wisest, who like Socrates, knows that his wisdom is in truth worth nothing”

Join the InvestorsHub Community

Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.