Wednesday, June 19, 2019 12:08:56 AM

4 Lost Utah Treasure Tales

MMMGYS

Utah is a paradise for mining history buffs and treasure seekers alike. a beautiful spiritual sound echos from this state. We will be showcasing this spiritual solace that comes out of this great state .

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Lost Treasures Just Waiting For You To Find

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Lost Loot from Castle Gate, Utah

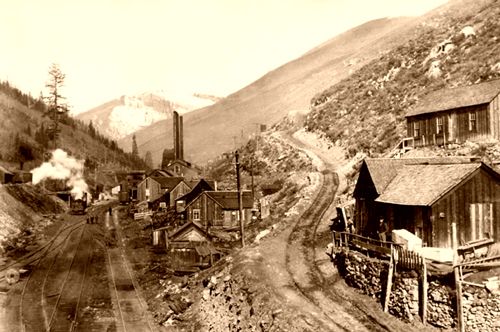

Castle Gate, Price Canyon, Utah, by Detroit Publishing, 1898

Castle Gate, Utah got its start in 1886 when the Pleasant Valley Coal Company began mining operations. This company town of miners was surrounded by rock formations, cliffs, mountains, and valleys, as well as another interesting element – outlaws. The remote region was a perfect hideout for cattle rustlers and train robbers, including one of the Old West’s most famous characters – Butch Cassidy and his gang of bandits.

On April 21, 1897, the train from Salt Lake City coasted into Castle Gate carrying the payroll for the Pleasant Valley Coal Company. Shortly before the train arrived, a lone cowboy had hitched his horse in front of the saloon and sat inside waiting for the sound of the train whistle. When he heard it, he left the saloon and made his way down to the train. As the lone cowboy sat watching, another cowboy was loitering near the stairway of the company office.

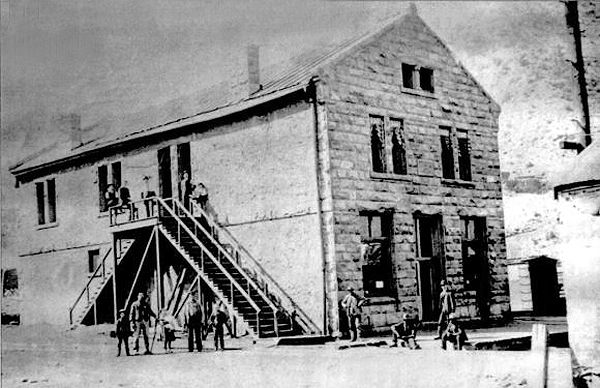

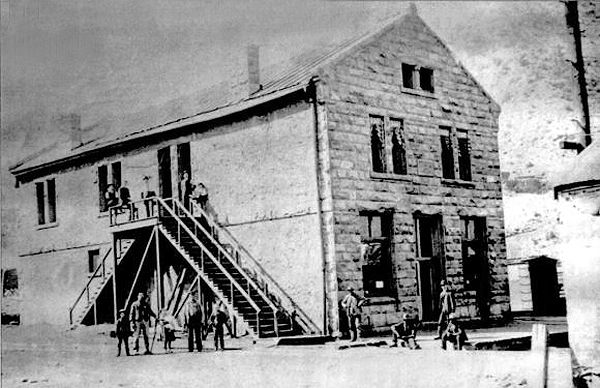

Pleasant Valley Coal Company Office, about 1898

As the baggage was unloaded from the train, three men, including the company paymaster and two guards, gathered the payroll, consisting of three bags, estimated at $8,800, emerged from the Baggage Room and headed to the Company office some 75 yards away.

However, before they reached the office, the lone cowboy held the three at gunpoint, taking the largest bag from the paymaster. In the meantime, the other man also approached, relieving them of another bag. In broad daylight, the two men had stolen the company payroll, with only one person attempting to interfere. When a customer at a nearby store tried to interlude, he was met with a gun.

The two cowboys, now known to have been Butch Cassidy, and Elza Lay, got on their horses and rode south, pursued by two citizens, one in a buggy, and the other on horseback shouting, “Bring that money back!” But it was too late, the pair was gone, along with an estimated $8,000.

Immediate attempts were made to reach the Sheriff by telephone, only to find the lines had been cut. Cassidy and Lay fled to Robbers Roost, cutting telegraph lines along the trail to prevent the news of the robbery from spreading to lawmen along their escape route.

The outlaw loot was never recovered and many believe it was hidden by the gang somewhere near Robbers Roost located along the Outlaw Trail, in southeastern Utah.

Officially incorporated as a town in 1914, Castle Gate would become news again years later, when on March 8, 1924, an explosion at Castle Gate Mine #2 claimed the lives of 172 miners. At the time it was the third worst mining disaster in the United States and is still the tenth deadliest to this day.

The town of Castle Gate was dismantled in 1974. All that’s left today is a historic marker along the highway north of Helper, Utah.

Castle Gate today

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

MMMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Spring Canyon, Utah Treasure

By Chuck Zehnder

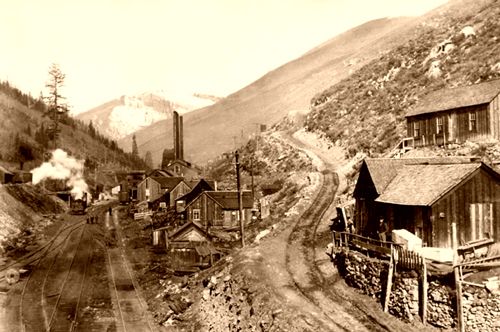

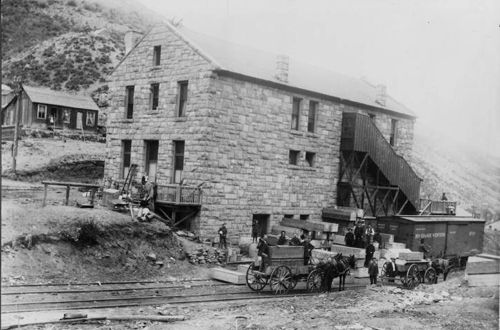

Spring Canyon Coal Company, William Shipler, 1925

About five miles west of the present Utah town of Helper, lies a small treasure hidden since the early 1920s. It isn’t a large treasure, but is certainly there to this day and would be a great find for someone.

Up Spring Canyon, there were a total of six mining camps, some of the towns of considerable size. One was Standardville. The town was built beginning in 1912 when F.A. Sweet opened a coal mine just a quarter of a mile north of the main canyon—the mine portal still exists.

Because the town was exceptionally well-designed and built, it became a “standard” for other mining towns and hence the name, Standardville. The town boasted a steam-heated swimming pool, fine billiard hall (the mosaic tile still exists) and a very modern company general store.

Not far from the company offices near the billiard hall was a two-inch pipe protruding from the ground. It was uncapped and in the days before OSHA was not unusual. But what lies at the bottom of that pipe is.

A small girl living in one of the company houses near the office and billiard hall found a cigar box her daddy had placed in a bureau drawer. It was very heavy she said, and she took it outside to play with it. After prying on the lid held in place by a small nail, she found the wooden cigar box contained newly minted silver dollars.

She said she played with them for a while and then walked over to the pipe and, one by one, dropped them into the pipe protruding from the ground. After they were all gone, she took the cigar box back to her home.

Needless to say, when her father found them missing, he questioned the family and she confessed. Her father asked her to show him where she had put them and she walked back to the area just east of the billiard hall and office. There they found a row of pipes that had been cut off—she could not tell which pipe she had dropped them into!

Today, little remains of the once-bustling town. In the mid-1970s most of it was bulldozed down, but there remain a few remnants of the town, including a few pipes protruding from the ground.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

MMMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

White Cliffs Lost Gold Ledge

White Cliffs of Utah

The White Cliffs of Utah, photo courtesy Bureau of Land Management

The high, rugged, and remote region of southern Utah holds a number of legends and tales hidden within its bold plateaus and multi-hued cliffs, one of which is the tale of the White Cliffs Gold Ledge.

The tale begins with an old prospector telling John Lorenzo Hubbell, of Hubbell Trading Post fame, about a cavern in the White Cliffs of Southern Utah that was laced with white quartz stalactites, caked with gold. As to why this old prospector, named George Brankerhoff, told the story to Hubbell, rather than following up himself, is a mystery.

At the time Brankerhoff shared the story with Hubbell in 1870, John Lorenzo was still a young man working as a sutler’s clerk at Fort Wingate, New Mexico. Hubbell never heard from the old prospector again, but he never forgot the story.

Three years later, when Hubbell was 20 years-old, the adventurous young man set out alone, traveling to Utah and following the old prospector’s directions in search of the gold ledge. Accurate remembering the tale, Hubbell first traveled to Kanab, Utah, then to Johnson Creek before turning eastward to the White Cliffs. He then followed the base of the White Cliffs to within three miles of Deer Springs Wash, where he would see a V-shaped cleft pointing downward. Brankerhoff had told him that the cleft would appear to be closed off from fallen sandstone; however, there would be a narrow space that could be squeezed through. Through the gap could be found a small stream of spring water that would disappear into the rocks beneath the V-shaped entrance. Once through the crevice, the space would open wider and deeper into a cavernous space, from the ceiling of which, would be hanging icicle-like quartz stringers laden with gold.

A seasoned desert traveler, Hubbell searched for weeks but was never able to find the V-shaped opening described by Brankerhoff. Finally, he decided to travel to Panguitch, Utah, some 65 miles north of Kanab to see if he could find out more information from the locals. Though he took a job in a general store, he was not accepted by the locals due to his Mexican heritage. To make matters worse, he was making friendly with a local girl who also had the attention of a Christian bishop. The next thing you know he found himself in a gunfight, and later was attacked by a dozen local men. Though Hubbell was wounded in the attack, he killed two of his attackers defending himself. He then stole a horse and fled to Lee’s Ferry, Arizona. Obviously, he had received no help from the locals regarding the terrain of the White Cliffs.

After his recovery, he returned to his birthplace in Parajito, New Mexico. A couple of years later, he would begin building his Indian Trading Post empire. Still, he wouldn’t let go of the Lost Ledge Tale. Over the next several decades, he enticed several prospectors into looking for the ledge in exchange for grubstaking them. However, none were able to find it.

Then a man named Warren Peters came along in 1891. Peters, a 61 year-old seasoned prospector, had just sold two silver claims in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado before making his way into New Mexico. With plans to prospect in the gold camps of the Mogollon Mountains in the southwest part of the state, Peters stopped in Gallup along the way. There he met John Lorenzo Hubbell. Once again, Hubbell saw opportunity and shared the tale with Peters, who was so interested that he traveled with Hubbell to his home in Ganado, Arizona. While there, Hubbell provided Peters with all of the details as well as drawing a map of the White Cliffs and Peters agreed to look. In May, 1891, Peters set out to see if he could find the lost ledge. One can only imagine how he might have felt when he spied the location. Making his way through the narrow passage, he spied the icicle-like formations. Wasting no time, he knocked down several 20-inch long stalactites, which scattered chunks of gold as they fell.

Filling several pouches with the gold, he then loaded them onto two burrows and headed to nearest railhead at Marysvale, some 80 miles to the north. He then traveled to Salt Lake City to sell his gold. However, he found that it would have to be shipped to Denver. After waiting more than a month he finally received the payment. Thrilled at the amount, he decided to make another trip back to the White Cliffs in August, 1891.

John Lorenzo Hubbell

John Lorenzo Hubbell started his first trading post in 1878, eventually creating a trading post empire of 30 such trading posts in Arizona, New Mexico, and California.

Re-supplied, he headed back, confident that he could find the cleft again. However, when he found himself at Deer Springs Wash, he knew he had gone too far. Surprised that he had missed it, he backtracked and began to search again. Back and forth he went search in vain for the V in the cliffs, but was not able to find it a second time.

Frustrated, he continued to look until it was almost winter before finally making his way back to Hubbell in Arizona. The two theorized throughout the winter wondering why it had been so easy for Peters to find the ledge the first time and impossible the second. They planned to return to Utah in the spring. However, when the time came Hubbell did not go, but rather sent a friend of his named Henry “Wild Hank” Sharp, and two Navajo Indians by the names of Little Chanter and Black Horse.

As the four prepared to leave on April 5, 1892, Hubbell warned them of dangerous men who inhabited that portion of southern Utah. However, the four prospectors were armed and set out on their way, along with 20 pack mules and plenty of supplies.

When they arrived at the White Cliffs, they found cattle grazing on the range, but paying no mind, set up camp at the base of the cliffs near a spring. The next day they split up into two pairs and began searching for the opening. Peters and Sharp returned to camp first to find six men there. Eyeing them warily, they slowly approached the camp and could see that their belongings had been gone through.

When Peters inquired as to what was going on, the “leader” of the bunch indicated that the area was rife with cattle thieves and it was his cattle that were grazing the range. Though Peters replied that they were prospectors, had no interest in the cattle, and the land was public domain, the cowboy adamantly insisted that they leave.

With a last threatening warning to vacate, the cowboys rode off. The four prospectors remained in camp for the evening and the next day decided they would not split up and would carry their arms with them as they continued to search for the crevice. However, when they examined their pistols and rifles, they found every one of them had been tampered with. Deciding to pack everything up, they planned to move the camp some four miles east to Deer Springs Wash. Moving slowly over the next four days, they searched for the lost ledge along the way before finally making a second camp near Deer Springs Wash.

Over the next several days, they continued their thorough search of the White Cliffs, while at night they worried about the dangerous cowboys. When they returned to camp after a day of searching, the Navajo found unknown tracks around the camp. Someone had obviously been there. They decided they would spend just one more day searching and then leave. In the meantime, they split up the camp, moving their pack animals and most of their supplies to the east side of the wash, while leaving their food and utensils at the original camp. After supper, the four moved to the east side of the wash to bed down for the night. However, as Peters and Sharp were discussing the situation, they spied 15 riders coming in from the west. Halting at the abandoned camp, one of them yelled that they were county officers and the prospectors were under arrest.

The four prospectors took cover and Peters responded, “What are the charges?”

The leader of the cowboys accused them of cattle rustling, but Peters responded that they were nothing more than a mob of cowboys and they would shoot if the cowboys advanced. After about a minute, bullets began to reign in Peters direction and the prospectors fired back. Hidden by cover, they were able to force back the cowboys, but in the meantime, Peters had taken a bullet in the leg.

Sharp and the Indians immediately began to pack up, bandaged Peters wound, and they took off back in the direction of Arizona. Fearful of being trailed, they moved as fast as they could throughout the night, not making camp until they were well into Arizona.

After allowing Peters some time to recover, they made their way back to Hubbell, who quickly made the decision that the gold was not worth pursuing if someone might die. Peters returned to his home in Kansas, and the other three to their respective homes and businesses. Hubbell never tried again to send prospectors into southern Utah.

Later, rumors circulated that a cowboy, maybe the same one who had threatened the prospectors, had blown shut the entrance to the crevice because he hadn’t wanted a bunch of prospectors on “his range.”

The legend says that the lost ledge of gold is still hidden somewhere in the White Cliffs. However, these lands are now part of the National Park System, which does not allow treasure hunting.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

MMMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Winter Quarters, Utah – Hidden Loot in a Ghost Town

By Chuck Zehnder

Winter Quarters, Utah, 1900

“There’s gold in them thar hills!” was a cry a few years ago regarding Winter Quarters, a Utah ghost town and mining camp. That cry came years after Winter Quarters was abandoned and for reasonable cause. First, a little history of the town.

Winter Quarters was first opened by George Matson in the spring of 1875.

“When we arrived in Pleasant Valley, later the site of Winter Quarters, we started right in to survey Pleasant Valley township and later we did assessment work on the claims.

Phil Beard, John Nelson and I started No. 1 tunnel and drove the first hundred feet into the hillside. Later, thousands of tons of coal were hauled out of this entry. I helped dig from the five-foot vein, the first load of coal ever shipped out of the valley,” so said Matson in an Aug. 23, 1928 issue of The Sun newspaper, published at Price.”

The high mountain ghost town in extreme northwestern Carbon County, became known as Winter Quarters because John Nelson and Abram Taylor wintered there in 1875 to hold the claim they had filed.

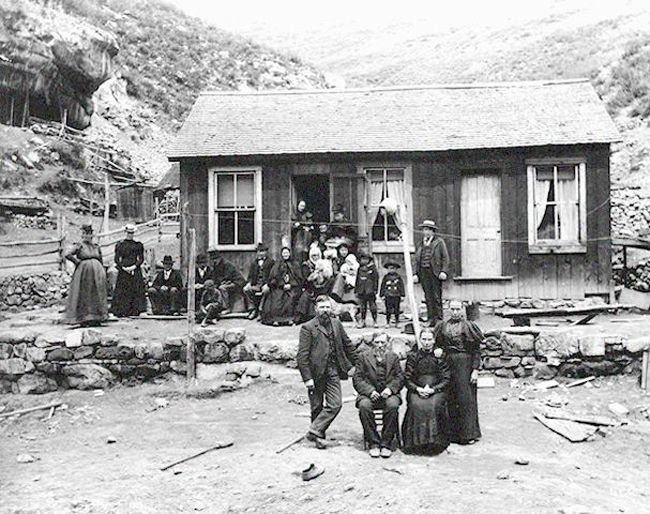

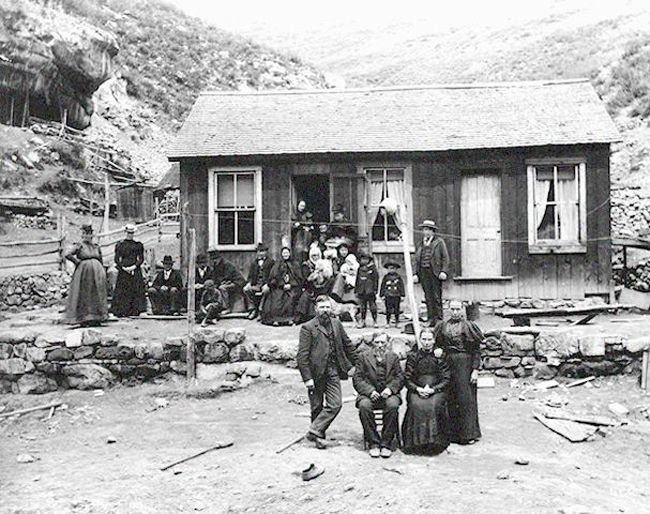

People of Winter Quarters, Utah

Two years later a group of men from Sanpete County came over the mountain to begin the town and continually work the mine. They intended to leave before winter, but an early snowstorm trapped the men. When their supplies ran out in February 1878, they then walked out to the north, eventually reaching the town of Tucker (now a ghost town and rest stop) in Spanish Fork Canyon.

When the great tonnage of coal in the mountain was known, more people began moving into the burgeoning town. As more and more coal was mined, the need for a railroad became apparent. Some of the residents got together and bought out a dry goods firm in the east and paid railroad workers with clothing and fabrics.

That old railroad bed is now a dirt road leading from the Tucker rest area on US-6 up the mountain onto what is known today as Skyline Drive and then down into Pleasant Valley. The railroad became known as the Calico Line.

May Day, 1900, started out with a clear sun shining up the valley into the town as 303 miners headed up to the mine portal. This mine was considered one of the safest in the country and had been inspected by Gomer Thomas, state mine inspector, on March 8.

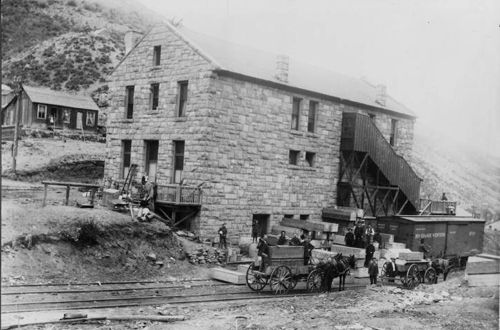

winters quarters utah

After the mining disaster caskets brought in from Salt Lake City and Denver were unloaded at the Wasatch Store in Winter Quarters, Utah. Photo courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

But at 10:15 a.m. everyone in the mountain town felt the ground shake. Some people thought someone had fired off an explosion to celebrate Dewey Day. Soon, the horrible truth spread through the town like wildfire. A giant explosion had occurred in the mine.

Mothers and daughters were seen hurrying toward the mine portal, “faces blanched with fear, hoping against hope that their loved ones in some way had escaped. Soon the realization came that the miners were caught – caught like rats in a trap with no chance of escape,” reported Charles Madsen in his account of the disaster.

When rescue and recovery teams were finally able to enter the horizontal shafts, they found “men piled in heaps, burned beyond recognition. The bodies were removed as fast as possible and the school, the church, and other available buildings were requisitioned as morgues.

When the accounting was done, 104 had escaped, seven of them seriously injured, and 199 killed in the mine blast. The town was 28 years from being a total ghost town.

When Pleasant Valley Coal Company opened mines at Castle Gate, far below Pleasant Valley, it spelled the end of the long-haul operations at Winter Quarters. Production decreased steadily and in 1928 the mine was closed and the town abandoned.

For many years the buildings stood mute in that mountain valley: windows boarded shut, roof shingles slowly slipping and walls rotting into dust. The school no longer heard the sounds of children laughing and there was no need for a janitor to clean the spring-time mud from the floors.

Eventually, the buildings collapsed or were torn down by scavengers and today only grass-covered foundations remain of what was Utah’s first coal camp. No industrial sounds in the quiet valley today, only a bubbling stream and the clicking of mule deer hooves on the rocks. But is that all that remains?

Speculation over the years about buried gold has frequently come into conversations about the mining town.

There is no question about the miners being paid in gold and silver coins. Just three years earlier, Butch Cassidy and Elza Lay had robbed the Pleasant Valley payroll when the money arrived by train. Their loot was $7,000 in gold double eagles. They dropped $700 in silver.

Couple that payroll with the fact that there was no bank at Winter Quarters and it is easy to see how many believe some of those miners had cached gold coins among the rocks or under fence posts behind their homes on the valley side. If they had not told wives of the cache, knowledge of it died with the miners that May Day in 1900.

Some have looked over the years for lost gold in the old townsite. None has ever reported finding some.

Can it be that the ghosts of those miners stand watch over buried gold double eagles?

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Topaz Crystal Treasures Popping Out The Ground in Utah

MMMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Mines of Utah

MMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

.jpg)

MMMGYS

Utah is a paradise for mining history buffs and treasure seekers alike. a beautiful spiritual sound echos from this state. We will be showcasing this spiritual solace that comes out of this great state .

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Lost Treasures Just Waiting For You To Find

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Lost Loot from Castle Gate, Utah

Castle Gate, Price Canyon, Utah, by Detroit Publishing, 1898

Castle Gate, Utah got its start in 1886 when the Pleasant Valley Coal Company began mining operations. This company town of miners was surrounded by rock formations, cliffs, mountains, and valleys, as well as another interesting element – outlaws. The remote region was a perfect hideout for cattle rustlers and train robbers, including one of the Old West’s most famous characters – Butch Cassidy and his gang of bandits.

On April 21, 1897, the train from Salt Lake City coasted into Castle Gate carrying the payroll for the Pleasant Valley Coal Company. Shortly before the train arrived, a lone cowboy had hitched his horse in front of the saloon and sat inside waiting for the sound of the train whistle. When he heard it, he left the saloon and made his way down to the train. As the lone cowboy sat watching, another cowboy was loitering near the stairway of the company office.

Pleasant Valley Coal Company Office, about 1898

As the baggage was unloaded from the train, three men, including the company paymaster and two guards, gathered the payroll, consisting of three bags, estimated at $8,800, emerged from the Baggage Room and headed to the Company office some 75 yards away.

However, before they reached the office, the lone cowboy held the three at gunpoint, taking the largest bag from the paymaster. In the meantime, the other man also approached, relieving them of another bag. In broad daylight, the two men had stolen the company payroll, with only one person attempting to interfere. When a customer at a nearby store tried to interlude, he was met with a gun.

The two cowboys, now known to have been Butch Cassidy, and Elza Lay, got on their horses and rode south, pursued by two citizens, one in a buggy, and the other on horseback shouting, “Bring that money back!” But it was too late, the pair was gone, along with an estimated $8,000.

Immediate attempts were made to reach the Sheriff by telephone, only to find the lines had been cut. Cassidy and Lay fled to Robbers Roost, cutting telegraph lines along the trail to prevent the news of the robbery from spreading to lawmen along their escape route.

The outlaw loot was never recovered and many believe it was hidden by the gang somewhere near Robbers Roost located along the Outlaw Trail, in southeastern Utah.

Officially incorporated as a town in 1914, Castle Gate would become news again years later, when on March 8, 1924, an explosion at Castle Gate Mine #2 claimed the lives of 172 miners. At the time it was the third worst mining disaster in the United States and is still the tenth deadliest to this day.

The town of Castle Gate was dismantled in 1974. All that’s left today is a historic marker along the highway north of Helper, Utah.

Castle Gate today

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

MMMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Spring Canyon, Utah Treasure

By Chuck Zehnder

Spring Canyon Coal Company, William Shipler, 1925

About five miles west of the present Utah town of Helper, lies a small treasure hidden since the early 1920s. It isn’t a large treasure, but is certainly there to this day and would be a great find for someone.

Up Spring Canyon, there were a total of six mining camps, some of the towns of considerable size. One was Standardville. The town was built beginning in 1912 when F.A. Sweet opened a coal mine just a quarter of a mile north of the main canyon—the mine portal still exists.

Because the town was exceptionally well-designed and built, it became a “standard” for other mining towns and hence the name, Standardville. The town boasted a steam-heated swimming pool, fine billiard hall (the mosaic tile still exists) and a very modern company general store.

Not far from the company offices near the billiard hall was a two-inch pipe protruding from the ground. It was uncapped and in the days before OSHA was not unusual. But what lies at the bottom of that pipe is.

A small girl living in one of the company houses near the office and billiard hall found a cigar box her daddy had placed in a bureau drawer. It was very heavy she said, and she took it outside to play with it. After prying on the lid held in place by a small nail, she found the wooden cigar box contained newly minted silver dollars.

She said she played with them for a while and then walked over to the pipe and, one by one, dropped them into the pipe protruding from the ground. After they were all gone, she took the cigar box back to her home.

Needless to say, when her father found them missing, he questioned the family and she confessed. Her father asked her to show him where she had put them and she walked back to the area just east of the billiard hall and office. There they found a row of pipes that had been cut off—she could not tell which pipe she had dropped them into!

Today, little remains of the once-bustling town. In the mid-1970s most of it was bulldozed down, but there remain a few remnants of the town, including a few pipes protruding from the ground.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

MMMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

White Cliffs Lost Gold Ledge

White Cliffs of Utah

The White Cliffs of Utah, photo courtesy Bureau of Land Management

The high, rugged, and remote region of southern Utah holds a number of legends and tales hidden within its bold plateaus and multi-hued cliffs, one of which is the tale of the White Cliffs Gold Ledge.

The tale begins with an old prospector telling John Lorenzo Hubbell, of Hubbell Trading Post fame, about a cavern in the White Cliffs of Southern Utah that was laced with white quartz stalactites, caked with gold. As to why this old prospector, named George Brankerhoff, told the story to Hubbell, rather than following up himself, is a mystery.

At the time Brankerhoff shared the story with Hubbell in 1870, John Lorenzo was still a young man working as a sutler’s clerk at Fort Wingate, New Mexico. Hubbell never heard from the old prospector again, but he never forgot the story.

Three years later, when Hubbell was 20 years-old, the adventurous young man set out alone, traveling to Utah and following the old prospector’s directions in search of the gold ledge. Accurate remembering the tale, Hubbell first traveled to Kanab, Utah, then to Johnson Creek before turning eastward to the White Cliffs. He then followed the base of the White Cliffs to within three miles of Deer Springs Wash, where he would see a V-shaped cleft pointing downward. Brankerhoff had told him that the cleft would appear to be closed off from fallen sandstone; however, there would be a narrow space that could be squeezed through. Through the gap could be found a small stream of spring water that would disappear into the rocks beneath the V-shaped entrance. Once through the crevice, the space would open wider and deeper into a cavernous space, from the ceiling of which, would be hanging icicle-like quartz stringers laden with gold.

A seasoned desert traveler, Hubbell searched for weeks but was never able to find the V-shaped opening described by Brankerhoff. Finally, he decided to travel to Panguitch, Utah, some 65 miles north of Kanab to see if he could find out more information from the locals. Though he took a job in a general store, he was not accepted by the locals due to his Mexican heritage. To make matters worse, he was making friendly with a local girl who also had the attention of a Christian bishop. The next thing you know he found himself in a gunfight, and later was attacked by a dozen local men. Though Hubbell was wounded in the attack, he killed two of his attackers defending himself. He then stole a horse and fled to Lee’s Ferry, Arizona. Obviously, he had received no help from the locals regarding the terrain of the White Cliffs.

After his recovery, he returned to his birthplace in Parajito, New Mexico. A couple of years later, he would begin building his Indian Trading Post empire. Still, he wouldn’t let go of the Lost Ledge Tale. Over the next several decades, he enticed several prospectors into looking for the ledge in exchange for grubstaking them. However, none were able to find it.

Then a man named Warren Peters came along in 1891. Peters, a 61 year-old seasoned prospector, had just sold two silver claims in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado before making his way into New Mexico. With plans to prospect in the gold camps of the Mogollon Mountains in the southwest part of the state, Peters stopped in Gallup along the way. There he met John Lorenzo Hubbell. Once again, Hubbell saw opportunity and shared the tale with Peters, who was so interested that he traveled with Hubbell to his home in Ganado, Arizona. While there, Hubbell provided Peters with all of the details as well as drawing a map of the White Cliffs and Peters agreed to look. In May, 1891, Peters set out to see if he could find the lost ledge. One can only imagine how he might have felt when he spied the location. Making his way through the narrow passage, he spied the icicle-like formations. Wasting no time, he knocked down several 20-inch long stalactites, which scattered chunks of gold as they fell.

Filling several pouches with the gold, he then loaded them onto two burrows and headed to nearest railhead at Marysvale, some 80 miles to the north. He then traveled to Salt Lake City to sell his gold. However, he found that it would have to be shipped to Denver. After waiting more than a month he finally received the payment. Thrilled at the amount, he decided to make another trip back to the White Cliffs in August, 1891.

John Lorenzo Hubbell

John Lorenzo Hubbell started his first trading post in 1878, eventually creating a trading post empire of 30 such trading posts in Arizona, New Mexico, and California.

Re-supplied, he headed back, confident that he could find the cleft again. However, when he found himself at Deer Springs Wash, he knew he had gone too far. Surprised that he had missed it, he backtracked and began to search again. Back and forth he went search in vain for the V in the cliffs, but was not able to find it a second time.

Frustrated, he continued to look until it was almost winter before finally making his way back to Hubbell in Arizona. The two theorized throughout the winter wondering why it had been so easy for Peters to find the ledge the first time and impossible the second. They planned to return to Utah in the spring. However, when the time came Hubbell did not go, but rather sent a friend of his named Henry “Wild Hank” Sharp, and two Navajo Indians by the names of Little Chanter and Black Horse.

As the four prepared to leave on April 5, 1892, Hubbell warned them of dangerous men who inhabited that portion of southern Utah. However, the four prospectors were armed and set out on their way, along with 20 pack mules and plenty of supplies.

When they arrived at the White Cliffs, they found cattle grazing on the range, but paying no mind, set up camp at the base of the cliffs near a spring. The next day they split up into two pairs and began searching for the opening. Peters and Sharp returned to camp first to find six men there. Eyeing them warily, they slowly approached the camp and could see that their belongings had been gone through.

When Peters inquired as to what was going on, the “leader” of the bunch indicated that the area was rife with cattle thieves and it was his cattle that were grazing the range. Though Peters replied that they were prospectors, had no interest in the cattle, and the land was public domain, the cowboy adamantly insisted that they leave.

With a last threatening warning to vacate, the cowboys rode off. The four prospectors remained in camp for the evening and the next day decided they would not split up and would carry their arms with them as they continued to search for the crevice. However, when they examined their pistols and rifles, they found every one of them had been tampered with. Deciding to pack everything up, they planned to move the camp some four miles east to Deer Springs Wash. Moving slowly over the next four days, they searched for the lost ledge along the way before finally making a second camp near Deer Springs Wash.

Over the next several days, they continued their thorough search of the White Cliffs, while at night they worried about the dangerous cowboys. When they returned to camp after a day of searching, the Navajo found unknown tracks around the camp. Someone had obviously been there. They decided they would spend just one more day searching and then leave. In the meantime, they split up the camp, moving their pack animals and most of their supplies to the east side of the wash, while leaving their food and utensils at the original camp. After supper, the four moved to the east side of the wash to bed down for the night. However, as Peters and Sharp were discussing the situation, they spied 15 riders coming in from the west. Halting at the abandoned camp, one of them yelled that they were county officers and the prospectors were under arrest.

The four prospectors took cover and Peters responded, “What are the charges?”

The leader of the cowboys accused them of cattle rustling, but Peters responded that they were nothing more than a mob of cowboys and they would shoot if the cowboys advanced. After about a minute, bullets began to reign in Peters direction and the prospectors fired back. Hidden by cover, they were able to force back the cowboys, but in the meantime, Peters had taken a bullet in the leg.

Sharp and the Indians immediately began to pack up, bandaged Peters wound, and they took off back in the direction of Arizona. Fearful of being trailed, they moved as fast as they could throughout the night, not making camp until they were well into Arizona.

After allowing Peters some time to recover, they made their way back to Hubbell, who quickly made the decision that the gold was not worth pursuing if someone might die. Peters returned to his home in Kansas, and the other three to their respective homes and businesses. Hubbell never tried again to send prospectors into southern Utah.

Later, rumors circulated that a cowboy, maybe the same one who had threatened the prospectors, had blown shut the entrance to the crevice because he hadn’t wanted a bunch of prospectors on “his range.”

The legend says that the lost ledge of gold is still hidden somewhere in the White Cliffs. However, these lands are now part of the National Park System, which does not allow treasure hunting.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

MMMGYS

Lost ending waiting for you to find it.LOL

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Winter Quarters, Utah – Hidden Loot in a Ghost Town

By Chuck Zehnder

Winter Quarters, Utah, 1900

“There’s gold in them thar hills!” was a cry a few years ago regarding Winter Quarters, a Utah ghost town and mining camp. That cry came years after Winter Quarters was abandoned and for reasonable cause. First, a little history of the town.

Winter Quarters was first opened by George Matson in the spring of 1875.

“When we arrived in Pleasant Valley, later the site of Winter Quarters, we started right in to survey Pleasant Valley township and later we did assessment work on the claims.

Phil Beard, John Nelson and I started No. 1 tunnel and drove the first hundred feet into the hillside. Later, thousands of tons of coal were hauled out of this entry. I helped dig from the five-foot vein, the first load of coal ever shipped out of the valley,” so said Matson in an Aug. 23, 1928 issue of The Sun newspaper, published at Price.”

The high mountain ghost town in extreme northwestern Carbon County, became known as Winter Quarters because John Nelson and Abram Taylor wintered there in 1875 to hold the claim they had filed.

People of Winter Quarters, Utah

Two years later a group of men from Sanpete County came over the mountain to begin the town and continually work the mine. They intended to leave before winter, but an early snowstorm trapped the men. When their supplies ran out in February 1878, they then walked out to the north, eventually reaching the town of Tucker (now a ghost town and rest stop) in Spanish Fork Canyon.

When the great tonnage of coal in the mountain was known, more people began moving into the burgeoning town. As more and more coal was mined, the need for a railroad became apparent. Some of the residents got together and bought out a dry goods firm in the east and paid railroad workers with clothing and fabrics.

That old railroad bed is now a dirt road leading from the Tucker rest area on US-6 up the mountain onto what is known today as Skyline Drive and then down into Pleasant Valley. The railroad became known as the Calico Line.

May Day, 1900, started out with a clear sun shining up the valley into the town as 303 miners headed up to the mine portal. This mine was considered one of the safest in the country and had been inspected by Gomer Thomas, state mine inspector, on March 8.

winters quarters utah

After the mining disaster caskets brought in from Salt Lake City and Denver were unloaded at the Wasatch Store in Winter Quarters, Utah. Photo courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

But at 10:15 a.m. everyone in the mountain town felt the ground shake. Some people thought someone had fired off an explosion to celebrate Dewey Day. Soon, the horrible truth spread through the town like wildfire. A giant explosion had occurred in the mine.

Mothers and daughters were seen hurrying toward the mine portal, “faces blanched with fear, hoping against hope that their loved ones in some way had escaped. Soon the realization came that the miners were caught – caught like rats in a trap with no chance of escape,” reported Charles Madsen in his account of the disaster.

When rescue and recovery teams were finally able to enter the horizontal shafts, they found “men piled in heaps, burned beyond recognition. The bodies were removed as fast as possible and the school, the church, and other available buildings were requisitioned as morgues.

When the accounting was done, 104 had escaped, seven of them seriously injured, and 199 killed in the mine blast. The town was 28 years from being a total ghost town.

When Pleasant Valley Coal Company opened mines at Castle Gate, far below Pleasant Valley, it spelled the end of the long-haul operations at Winter Quarters. Production decreased steadily and in 1928 the mine was closed and the town abandoned.

For many years the buildings stood mute in that mountain valley: windows boarded shut, roof shingles slowly slipping and walls rotting into dust. The school no longer heard the sounds of children laughing and there was no need for a janitor to clean the spring-time mud from the floors.

Eventually, the buildings collapsed or were torn down by scavengers and today only grass-covered foundations remain of what was Utah’s first coal camp. No industrial sounds in the quiet valley today, only a bubbling stream and the clicking of mule deer hooves on the rocks. But is that all that remains?

Speculation over the years about buried gold has frequently come into conversations about the mining town.

There is no question about the miners being paid in gold and silver coins. Just three years earlier, Butch Cassidy and Elza Lay had robbed the Pleasant Valley payroll when the money arrived by train. Their loot was $7,000 in gold double eagles. They dropped $700 in silver.

Couple that payroll with the fact that there was no bank at Winter Quarters and it is easy to see how many believe some of those miners had cached gold coins among the rocks or under fence posts behind their homes on the valley side. If they had not told wives of the cache, knowledge of it died with the miners that May Day in 1900.

Some have looked over the years for lost gold in the old townsite. None has ever reported finding some.

Can it be that the ghosts of those miners stand watch over buried gold double eagles?

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Topaz Crystal Treasures Popping Out The Ground in Utah

MMMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Mines of Utah

MMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

.jpg)

Join the InvestorsHub Community

Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.