Wednesday, June 12, 2019 12:04:06 AM

9 and 3 Lost Washington State Treasure Tales

MMGYS*Lost treasure by state series

Hope your enJoying the show tonight

Great to have you with us <3

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Washington State Treasures Just Waiting to Be Found

Asotin County – Situated in the southeastern most corner of Washington in a remote mountainous area, is the ghost town of Rogersburg, with less than 25 residents today. A river boomtown stimulated by gold discoveries, the town was once accessible only by horse or by boat. In fact, it wasn’t until 1938, that a road from Asotin finally reached the small village. On or near Shovel Creek, off the Snake River, is thought to be the lost Shovel Creek Mine. Also near Rogersburg is said to be the Trio Lost Mine, as well as a hidden cache left by a long ago prospector. Yet another cache is said have been buried near Rogersburg by outlaw Charley Maguire after he robbed a stagecoach.

Bloom County – Located in the heart of Puget Sound is Vashon Island where a successful lumberman by the name of Lars Hanson lived in the 1870’s. On the banks of Judd Creek, near Burton, he was said to have hidden more than $200,00 in gold coins.

Clark County – For more than a century, rumors have abounded that there is a rich mine hidden in the Cascade Mountains. Said to have been located near the headwaters of the Lewis River somewhere in the wilderness between Mt. St. Helens and Mt. Adams, the mine was worked by an old Spaniard in the 1880’s. The miner often journeyed south to The Dalles, Oregon, to bank his gold at the French & Company Bank. On a number of occasions, other prospectors would attempt to follow him as he returned to the mine, but the old Spaniard was clever and always eluded them, using a number of tricks including putting the shoes on his mule backwards. Suddenly the old Spaniard stopped appearing to bank his gold and local miners began to wonder what had happened to him. About a year later, numerous Yakama Indians began showing in a number of stores in Washington, paying for goods with gold nuggets. When asked where they had obtained the gold, the Indians refused to answer. Soon, rumors began to circulate that the Indians had found the Spaniard’s mine. Later, a skeleton of a man and a mule was discovered near Spirit Lake by Mt. St. Helens. It was thought to have been the old Spaniard who had been killed by the Indians. The mine, that some say is hidden behind a waterfall in a cavern, has never been found.

Grant County – Outlaws are said to have buried some $30,000 in gold in a cave somewhere on Sentinel Mountain in the Saddle Mountain Range, about three miles southeast of Beverly.

Pacific County – Captain James Scarborough was the first white settler north of the Columbia River and built a frontier cabin in 1843. Allegedly, he buried a treasure near his cabin on what is now Fort Columbia. If a treasure is buried there, it will have to stay hidden, as the historic fort is now a Washington State Park.

Stevens County – The Lost Doukhober Mine, discovered in 1929, is said to be located in the northern part of Stevens County. Ore from this mine assayed at 1,000 oz of silver per ton. Another lost cache is said to be buried at Robbers’ Roost near Fruitland.

Stevens County – Located near the town of Colville, a treasure known as The Highgrader’s Poor Farm treasure is said to be hidden. Poor Farm treasure refers to “Matte” – a crude mixture of sulphides produced when smelting gold. It is thought to be buried near an old brickyard.

Walla Walla County – According to the tales, bandits took a number of gold bars in a train robbery near Wallula in the late 19th century.

Intending to catch a boat for Portland, they missed it and buried their stolen cache near old Fort Walla Walla. Later the bandits were shot before ever telling of the hiding place of the loot. Today, the old fort is gone and the location has become Fort Walla Walla Park located at the western edge of Walla Walla, Washington.

Yakima County – Pierre Rabado’s Lost Mine is thought to be located near Mt. Adams. It could also be in Skamania County.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

An Anchor in Bellingham Bay

George Vancouver

Between the years of 1791 and 1794, Captain George Vancouver, a British Officer, commanded the HMS Discovery and its accompanying ships on an exploratory voyage of the Pacific Northwest. While surveying the northern Pacific Ocean, he and his crew were the first to record the sighting of Mount St. Helens and the first to explore Puget Sound. Following the coasts of Oregon and Washington and intending to explore every bay and outlet of the region, he sent men in smaller boats to explore the Columbia River and enter the strait of Juan de Fuca.

While the smaller vessels explored the many channels and rivers along the coast, the larger ships, including the Armed Tender of the HMS Discovery, called the Chatham, often anchored in safe harbors. On April 29, 1792, the ships entered the Straits of Juan de Fuca and anchored in the calm waters of Discovery Bay. Utilizing the bay as a base, Vancouver and his men explored the waters of Admiralty Inlet and Hood Canal.

After several weeks, the Chatham began to sail north across the Straits of Juan de Fuca to explore the San Juan and Lopez Islands. After successfully doing so, the Chatham sailed southward in May to rejoin the HMS Discovery and continue their explorations south.

HMS Discovery

The explorations continued as far as Commencement Bay in Tacoma, before turning around and returning north, where the waters were safer. Arriving at Puget Sound, they found a storm raging with severe currents and tides. Crossing an unknown channel, the Chatham was caught by a flood tide and swept helpless. To slow her progress, her stream anchor was dropped but the strain was too much and the cable snapped. However, the Chatham survived and after sweeping the waters unsuccessfully for the anchor, the ship rejoined the HMS Discovery.

Vancouver would write in his journal on June 9, 1792:

“We found tides here extremely rapid, and on the 9th in endeavoring to get around a point to the Bellingham Bay we were swept leeward of it with great impetuosity. We let go the anchor in 20 fathoms but in bringing it up such was the force of the tide that we parted the cable. At slack water we swept for the anchor but could not get it. After several fruitless attempts, we were at last obliged to leave it.”

For treasure hunting divers, the anchor would be a great find..and indeed it was. In 2008, Anchor Ventures, LLC of Seattle decided that instead of searching the Channel, they would search off Whidbey Island’s northwestern shore. Their bet that the Chatham wasn’t with the Discovery at the time of the storm paid off. Anchor Ventures pulled up what they believe to be the long lost anchor. It was finally pulled up in 2014, and the team has been trying to prove its identity since. Skeptics say not so fast, this anchor is heavier than those of the late 1700’s.

Is the anchor still there? The search continues for the doubters of the 2008 find.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

MMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

John Tornow – The Wild Man of the Wynoochee, Washington

Satsop River, Washington

Coming from a respected family that homesteaded near the Satsop River, John Tornow was born on September 4, 1880. From the time he was just a small child, he preferred the unexplored wilderness near his home as his playground. As he grew, he spent more time with wild animals than he did with people.

When the boy was just ten years old his brother Ed killed his beloved dog and young John retaliated by killing Ed’s own dog. It was at this time that Tornow began to shun people altogether, vanishing into the woods for weeks at a time.

Hunting only for food, he learned to track as well as any Indian and his shooting skills quickly became legendary. He would return to his home only for brief visits with his parents, usually bearing gifts of game. By the time he reached his teen years, almost any animal would approach him unafraid, and his family had begun to think he was just a little bit crazy.

As his brothers entered the logging business, eventually owning their own company, Tornow occasionally worked as a logger, but more often continued to maintain his solitary ways in the wilderness. Living off the land, dressing in animal skins and shoes made of bark, John just wanted to be left alone with nature. Standing some 6”4” and weighing in at nearly 250 pounds, most people thought him a little strange, but harmless.

By the first decade of the 20th century, he was rarely venturing out of the woods but would occasionally watch the loggers as they were working. On one occasion he supposedly said to a logger, “I’ll kill anyone who comes after me. These are my woods.”

Convinced he was insane, his brothers captured him and committed him to a sanitarium in 1909. However, the facility, located deep in the heart of Oregon’s wilderness, was not able to contain the large man, as some 12 months later, he escaped into the forest.

Wynoochee Valley, Washington

Nothing was seen or heard of John for the next year until he began to occasionally visit his sister, her husband, and their twin sons, John and Will Bauer. He refused to have anything to do with his brothers, never having forgiven them for committing him to the sanitarium.

Spied occasionally with tangled hair, a long beard, and ragged clothes, his legend began to grow as people described him as a giant gorilla-like man seen running through the forest. Loggers would tell that he appeared to be a large hairy “beast” that would seemingly appear out of nowhere before once again vanishing into the forest.

In September 1911, Tornow shot and killed a cow grazing in a clearing by his sister’s small two-room cabin on the Olympic Peninsula. While he was dressing out his kill, a bullet whizzed over his head and dropping his knife, he lifted his rifle and fired three times in the direction from where the bullet had originated. When he went into the brush, he found his two 19-year-old twin nephews lying dead on the ground.

As to why John and Will Bauer shot at Tornow, it was suggested that the pair thought he was a bear feeding off of one of their herd. However, some historians believe that the boys intentionally made John Tornow their target. Though the truth will always remain a mystery, the mountain man, no doubt reasoned that someone was trying to capture or kill him when he returned fire. After seeing the dead bodies, Tornow quickly fled the scene disappearing into the deeply forested Wynoochee Valley. This incident would become the beginning of a legend that would grow large over the next several years and ultimately result in the death of the solitary mountain man.

William and John Bauer

When the Bauer boys did not return from home, their family contacted Chehalis County (Chehalis County would become Grays Harbor County in 1915) Deputy Sheriff John McKenzie. Soon, the deputy rounded up a group of more than 50 men to search for the brothers, who soon returned with the two dead bodies. Both had been shot in the head and stripped of their weapons.

McKenzie immediately announced that the shooting had to have been committed by John Tornow and a posse was rounded up to search for the wild man living in the forest. In no time, loggers and farmers making up the posse were roaming the Satsop area and the lower regions of the Wynoochee Valley, wary of the large man that they knew to have the intuition of an animal and the skills of an Indian.

The posse was skittish, terrified of the wild man, and when one group heard a sound in the brush, a shot rang out, killing a cow. Though the men were sure that Tornow was nearby each time they heard the slightest noise in the woods, they never spotted him.

The longer they searched and didn’t find the “ape-man” killer, the tales grew more and more exaggerated. Soon, the stories told of a cold-eyed giant constantly traversing the forest in search of prey, who soon earned such labels as “the Wild Man of the Wynoochee,” “the Cougar Man,” and “a Mad Daniel Boone.” With each telling, the story became larger and larger until the entire countryside was terrified. As the stories spread to the adjacent camps of Aberdeen, Montesano, Elma, and Hoquiam, no one felt safe with John Tornow on the prowl. Women and children were warned to stay indoors as the men oiled their hunting rifles and unleashed their dogs for protection.

As men continued to search into the winter they were forced into the lowlands due to deep snows. Tornow simply headed to higher terrain. Sometime later, the wild man broke into Jackson’s Country Grocery Store intending to help himself to a few provisions. Often he was known to burglarize cabins and stores in order to get what he needed to survive. However, on this occasion, he found more than just flour, salt, and matches, but also a strongbox filled with some $15,000. The grocery also served as the town’s bank.

In no time, Chehalis county offered a $1,000 reward for the return of the stolen money and despite their fears of the “wild man,” the number of men hunting Tornow dramatically increased. The blasts of gunfire could be heard echoing in the forest and on February 20, 1912, a gunshot-happy hunter killed a 17-year-old boy, mistaking him for Tornow.

The dense area where Tornow made his home is now part of the Olympic National Forest,

A few weeks later, a traveling prospector reported to Sheriff McKenzie that he had spotted Tornow at a camp in Oxbow. Together with Deputy Game Warden Albert V. Elmer, the pair headed out but found only a cold campfire at the point where Tornow had been spied. Sure that the money was buried somewhere close, the two began to look around. Though they were rewarded with two gold coins, they didn’t find the strongbox.

Sometime later both Sheriff McKenzie and Warden Elmer went missing and the reward was increased to $2,000. On March 16th, Deputy Sheriff A. L. Fitzgerald gathered up another posse to hunt for the “ape-man” in both Oxbow and Chehalis counties. Though they searched high and low for Tornow, what they found instead, were the bodies of Sheriff McKenzie and Albert Elmer. Both had been shot between the eyes and gutted with a knife.

Though the searches continued and Tornow was spied here and there, the mountain man continued to elude capture. A month later on April 16th, Deputy Giles Quimby, along with two other men by the names of Louis Blair and Charlie Lathrop, came upon a small shack made of bark. Sure that the crude cabin belonged to Tornow, Quimby wanted to head back for a posse, but the other two balked at having to share the bounty.

So, with guns ready, they approached the shack when a shot rang out, hitting Blair who fell into the nearby bushes. Lathrop returned fire but was immediately hit in the neck killing him instantly. Quimby, left alone with the marksman, desperately tried to negotiate with Tornow, telling him that all he wanted was the strongbox and promising to let the wanted man go free.

From his hiding place Tornow shouted, “It’s buried!”

Quimby continued to assert that he wanted nothing but the return of the money and would then leave John alone. Though Tornow was hesitant, not sure that Quimby would keep his word, the deputy assured him that he would let him go.

Deputy Giles Quimby

Finally, Tornow answered the deputy by stating, “It’s buried in Oxbow, by the boulder that look’s like a fish’s fin. Take it and leave me alone!”

Having retrieved the information from Tornow, Quimby didn’t keep his word, opening fire upon the foliage where John was hiding. Though no return shots were fired, Quimby wasn’t sure if he had hit the man or if Tornow might be just “playing dead.” Stealthily, Quimby scurried away through the woods.

When Quimby returned to Montesano, Sheriff Matthews gathered up another posse and the men began the trek back to the spot where Quimby had fired on Tornow. After cautiously approaching the trees, Tornow was found dead leaning against a tree. The men found $6.65 in silver coins on his body, identifying some of them as those taken from Jackson’s Grocery store.

Before Tornow’s body was even returned to Montesano, word had already reached the town that the “wild man” had been killed and curious gawkers began lining the street in order to get a peek at the legendary mountain man.

Deputy Sheriff Giles Quimby told newspaper reporters that John Tornow had “the most horrible face I ever saw. The shaggy beard and long hair, out of which gleamed two shining, murderous eyes, haunts me now. I could only see his face as he uncovered himself to fire a shot, and all the hatred that could fire the soul of a human being was evident.”

This further fueled the curiosity seekers’ desire to see the wildman’s face. In response, his brother Fred, who had traveled up from Portland, tried to prevent the body’s public display. However, when some 250 gawkers stormed the tiny morgue demanding to see the body, the overwhelmed coroner allowed them inside. Before it was said and done, the crowd required dozens of deputy sheriffs to prevent the nearly 700 citizens from tearing off bits of the dead man’s clothing and removing locks of his hair.

Fearing that those who were unable to view the body at the morgue would appear at the funeral, his service was held at the family’s old homestead. Immediately, postcards were printed that featured a photo of Tornow along with numerous newspaper articles with screaming headlines calling Tornow “The Great Outlaw of Western Washington.”

Of his brother’s death, Fred Tornow would, when questioned by the press, say: “I am glad John is dead. It was the best way now that it is over, and I would rather see him killed outright than linger in a prison cell.”

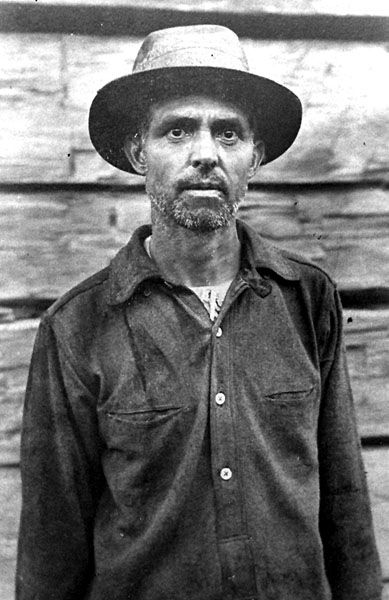

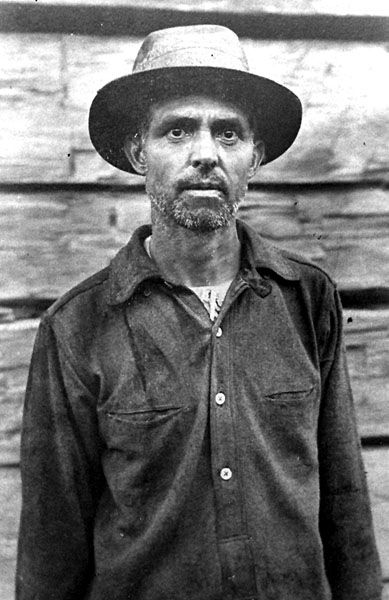

Customary in the days of the early 20th century, photos were taken of the dead. This photograph of John Tornow's corpse appeared on postcards the very day of his funeral.

Customary in the days of the early 20th century, photos were taken of the dead. This photograph of John Tornow’s corpse appeared on postcards the very day of his funeral.

The Oregonian newspaper noted that at the time of Tornow’s death he had $1,700 on deposit in a Montesano bank, owned real estate in Aberdeen, and was a part owner of a timber claim in Chehalis. Giles Quimby was proclaimed a hero for finally killing the feared “Wild Man of the Wynoochee,” so much so that he received offers to appear on stage to tell of his gruesome tale. Quimby politely turned down these offers.

When the furor of Tornow’s death had settled, Quimby went looking for the boulder that looked like a fish’s fin and was delighted when he found it. However, his happiness was short-lived, as search as he might, he never found the strongbox. Numerous other men followed in his footsteps, looking all over Oxbow, Washington, but the $15,000 treasure was never found.

The money is thought to be buried on the Wynoochee River where it turns into a large, horseshoe-shaped creek. However, a dam has since been built upstream, which may have caused a change in the river’s flow. Tornow said that he buried the cache near a fin-like rock. The hiding place is within the Olympic National Forest, which requires permission to hunt.

Tornow was buried in Matlock Cemetery in Grays Harbor, Washington, where his tombstone stands today.

Customary in the days of the early 20th century, photos were taken of the dead. This photograph of John Tornow’s corpse appeared on postcards the very day of his funeral.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

MMGYS*

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Victor Smith and a Tale of Three Lost Treasures

Port Townsend Customs House

In 1861, President Abraham Lincoln appointed a man named Victor Smith, a newspaper editor from Cincinnati, Ohio, as Collector of Customs for the District of Puget Sound, Washington. However, when Smith arrived, he immediately took a dislike to Port Townsend, thinking it no more than a city of “huts” populated by uncouth Westerners.

An ambitious man, Smith began to promote moving the Customs House from Port Townsend to Port Angeles. With the nation in the midst of the Civil War, he further supported his plan by advocating the idea that the British intended to join forces with the Confederates and the existing Port of Entry could be easily invaded from the British naval base on Vancouver Island in British Columbia.

In anticipation of the move, Smith, along with four other men, acquired land in Port Angeles and formed a Townsite Company to develop the new community. The townsfolk of Port Townsend soon learned of Smith’s plan, which of course, created feelings of hostility in the burgeoning community of Port Townsend.

When Smith’s letters to the Treasury Department failed to get immediate results, Smith traveled to Washington D.C. to promote his plan to fortify Port Angeles and relocate the Customs House there. Promoting Port Angeles’ superior location because it was nearer the ocean, he convinced Congress to move the Customs District of Puget Sound from Port Townsend to Port Angeles. It was made official in June 1862.

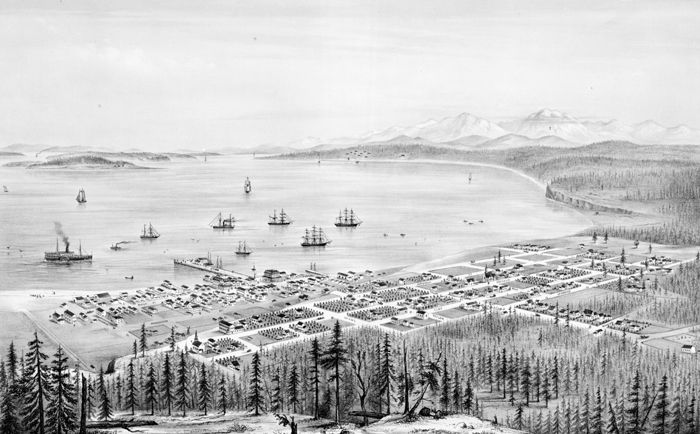

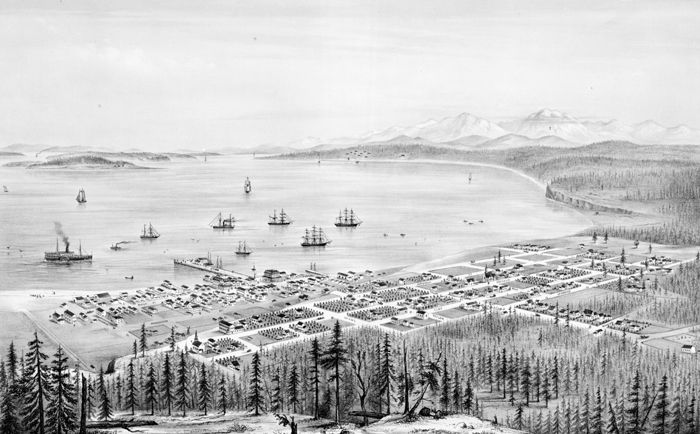

Port Townsend, Washington by E.S. Glover, 1878

However, all was not going exactly as Smith had planned. While he was celebrating his success on his return voyage to the west coast, the Acting Collector of Customs in Port Townsend, Lieutenant Merryman, was auditing the books of the Customs House. Finding the accounts short some $15,000, Merryman immediately reported the discrepancy to the Treasury Department by letter.

When Smith returned to Port Townsend on August 1, 1862, Lieutenant Merryman refused him access to the Customs House, accusing him of embezzlement and insisting that he would await official clearance from the Treasury Department before allowing Smith to return to his duties.

But Smith was not to be deterred. Returning to the ship on which he had arrived, he ordered the captain to train his three 12-pound cannons on the Customs House and the city’s commercial district. With the guns trained on the city, Merryman finally gave up the records and the ship sailed for Port Angeles.

Incensed, Port Townsend citizens soon traveled to Olympia to protest Smith’s actions to the governor. Though a federal grand jury indicted Smith with 13 counts of embezzlement and misuse of public funds, the Treasury Department quashed the indictment after their investigation.

In the meantime, Smith was constructing a large building in Port Angeles which served as both his family home and the Customs House. But, the Port Townsend citizens were not done fighting and began to build a case denouncing Smith and the transfer of the Port of Entry to Port Angeles.

After Smith completed the building in Port Angeles that served as both his home and the Customs House, a portion of it was rented to the government for its use. However, the building was to be short-lived as in December 1863, a landslide in the Olympic Mountains caused the dam to burst, sending a torrent of water through the town. Leveling most of the city and sweeping the Customs House into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, two customs employees were killed in the disaster. Smith was out of town and his family was spared.

It was this disaster that leads to the first treasure tale. Inside the Customs House was a strongbox that allegedly held $1,500 in bank notes and numerous $20 gold coins valued at $7,500 at the time. While some say this money was funds that Smith had stolen during his tenure as a Customs Agent, others contend it was money rightfully paid to him by the government for his home in Ohio. In any event, the strongbox was swept away in the flood and no trace of it has ever been found.

Finally, President Lincoln removed Smith as a Customs Collector in January 1864. However, his “friends” at the Treasury Department gave him a new role as a special agent.

In this new job, Smith was often tasked with transporting large sums of money. In 1865, he and his family had been on the east coast and while returning to San Francisco on the Gold Rule, Smith was tasked with transporting a large amount of payroll funds to San Francisco. However, on the ships passage from New York to San Juan, it wrecked on the Roncador Reef near the Isthmus of Panama. Though no loss of life was suffered, the ship floundered for 11 days as the 700 passengers survived on supplies salvaged from the vessel. When they were rescued by two gunboats, the passengers were taken to Panama. In the mass confusion following the wreck, the strongbox containing the money mysteriously disappeared. Smith remained on the reef endeavoring to salvage the chest containing the money. The tale continues that with the aid of a diver, the chest was recovered; however, the gold was missing. Though Smith accused the captain of the theft, many thought it was Smith himself who had absconded with the money.

In the meantime, Smith’s family had crossed the Panama Canal by railroad and returned to San Francisco on the sailing ship “America.” Two weeks later, Smith followed, reaching San Francisco and transferring to the Brother Jonathan on July 28, 1865, for the trip to Port Angeles. Did the payroll funds from the east coast wind up at the bottom of the ocean near the Roncador Reef or did it go with Smith when he finally made his way to San Francisco?

After transferring to the Brother Jonathan, Smith was again accompanying a large amount of money – some $200,000 to pay the troops at Fort Vancouver, Walla Walla, and other posts in the Northwest. The ship was also thought to have been carrying crates of $20 gold pieces for transfer to Haskins and Company as well as Wells Fargo. A government Indian Agent for the Northwestern Region may have also brought gold coins on board for annual treaty payments to the tribes.

As the Brother Jonathan passed through the Golden Gate and headed north, they faced a strong headwind and heavy seas, which continually worsened during its journey. The next day, the ship pulled into the harbor at Crescent City to offload cargo. On her way again, the storm was building and the ship headed westward to avoid the rocks of St. George’s Reef. As the storm continued to rage, Captain DeWolf decided to return to Crescent City, California to wait out the storm.

However, on July 30, 1865, the ship hit a rock and began to break up. Many of the passengers loaded into life boats were immediately thrown out as the smaller boats capsized. In the end, of the 244 people on board, 19 only people survived in a damaged boat that hobbled into the Crescent City harbor. For weeks, bodies washed ashore, but of the gold and money on board, it was never found. Victor Smith was one of the casualties.

In 1866, the Customs Port of entry was returned to Port Townsend, among great rejoicing by the citizens.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Mining Pyrite and Quartz Crystals

MMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Where Can I Find Gold In Washington State?

MMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

click on top part of videos for links

.jpg)

MMGYS*Lost treasure by state series

So many Legendary bands have came out from Washington State, the Wilson Sisters/Heart just the tip of the iceberg

Hope your enJoying the show tonight

Great to have you with us <3

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Washington State Treasures Just Waiting to Be Found

Asotin County – Situated in the southeastern most corner of Washington in a remote mountainous area, is the ghost town of Rogersburg, with less than 25 residents today. A river boomtown stimulated by gold discoveries, the town was once accessible only by horse or by boat. In fact, it wasn’t until 1938, that a road from Asotin finally reached the small village. On or near Shovel Creek, off the Snake River, is thought to be the lost Shovel Creek Mine. Also near Rogersburg is said to be the Trio Lost Mine, as well as a hidden cache left by a long ago prospector. Yet another cache is said have been buried near Rogersburg by outlaw Charley Maguire after he robbed a stagecoach.

Bloom County – Located in the heart of Puget Sound is Vashon Island where a successful lumberman by the name of Lars Hanson lived in the 1870’s. On the banks of Judd Creek, near Burton, he was said to have hidden more than $200,00 in gold coins.

Clark County – For more than a century, rumors have abounded that there is a rich mine hidden in the Cascade Mountains. Said to have been located near the headwaters of the Lewis River somewhere in the wilderness between Mt. St. Helens and Mt. Adams, the mine was worked by an old Spaniard in the 1880’s. The miner often journeyed south to The Dalles, Oregon, to bank his gold at the French & Company Bank. On a number of occasions, other prospectors would attempt to follow him as he returned to the mine, but the old Spaniard was clever and always eluded them, using a number of tricks including putting the shoes on his mule backwards. Suddenly the old Spaniard stopped appearing to bank his gold and local miners began to wonder what had happened to him. About a year later, numerous Yakama Indians began showing in a number of stores in Washington, paying for goods with gold nuggets. When asked where they had obtained the gold, the Indians refused to answer. Soon, rumors began to circulate that the Indians had found the Spaniard’s mine. Later, a skeleton of a man and a mule was discovered near Spirit Lake by Mt. St. Helens. It was thought to have been the old Spaniard who had been killed by the Indians. The mine, that some say is hidden behind a waterfall in a cavern, has never been found.

Grant County – Outlaws are said to have buried some $30,000 in gold in a cave somewhere on Sentinel Mountain in the Saddle Mountain Range, about three miles southeast of Beverly.

Pacific County – Captain James Scarborough was the first white settler north of the Columbia River and built a frontier cabin in 1843. Allegedly, he buried a treasure near his cabin on what is now Fort Columbia. If a treasure is buried there, it will have to stay hidden, as the historic fort is now a Washington State Park.

Stevens County – The Lost Doukhober Mine, discovered in 1929, is said to be located in the northern part of Stevens County. Ore from this mine assayed at 1,000 oz of silver per ton. Another lost cache is said to be buried at Robbers’ Roost near Fruitland.

Stevens County – Located near the town of Colville, a treasure known as The Highgrader’s Poor Farm treasure is said to be hidden. Poor Farm treasure refers to “Matte” – a crude mixture of sulphides produced when smelting gold. It is thought to be buried near an old brickyard.

Walla Walla County – According to the tales, bandits took a number of gold bars in a train robbery near Wallula in the late 19th century.

Intending to catch a boat for Portland, they missed it and buried their stolen cache near old Fort Walla Walla. Later the bandits were shot before ever telling of the hiding place of the loot. Today, the old fort is gone and the location has become Fort Walla Walla Park located at the western edge of Walla Walla, Washington.

Yakima County – Pierre Rabado’s Lost Mine is thought to be located near Mt. Adams. It could also be in Skamania County.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

An Anchor in Bellingham Bay

George Vancouver

Between the years of 1791 and 1794, Captain George Vancouver, a British Officer, commanded the HMS Discovery and its accompanying ships on an exploratory voyage of the Pacific Northwest. While surveying the northern Pacific Ocean, he and his crew were the first to record the sighting of Mount St. Helens and the first to explore Puget Sound. Following the coasts of Oregon and Washington and intending to explore every bay and outlet of the region, he sent men in smaller boats to explore the Columbia River and enter the strait of Juan de Fuca.

While the smaller vessels explored the many channels and rivers along the coast, the larger ships, including the Armed Tender of the HMS Discovery, called the Chatham, often anchored in safe harbors. On April 29, 1792, the ships entered the Straits of Juan de Fuca and anchored in the calm waters of Discovery Bay. Utilizing the bay as a base, Vancouver and his men explored the waters of Admiralty Inlet and Hood Canal.

After several weeks, the Chatham began to sail north across the Straits of Juan de Fuca to explore the San Juan and Lopez Islands. After successfully doing so, the Chatham sailed southward in May to rejoin the HMS Discovery and continue their explorations south.

HMS Discovery

The explorations continued as far as Commencement Bay in Tacoma, before turning around and returning north, where the waters were safer. Arriving at Puget Sound, they found a storm raging with severe currents and tides. Crossing an unknown channel, the Chatham was caught by a flood tide and swept helpless. To slow her progress, her stream anchor was dropped but the strain was too much and the cable snapped. However, the Chatham survived and after sweeping the waters unsuccessfully for the anchor, the ship rejoined the HMS Discovery.

Vancouver would write in his journal on June 9, 1792:

“We found tides here extremely rapid, and on the 9th in endeavoring to get around a point to the Bellingham Bay we were swept leeward of it with great impetuosity. We let go the anchor in 20 fathoms but in bringing it up such was the force of the tide that we parted the cable. At slack water we swept for the anchor but could not get it. After several fruitless attempts, we were at last obliged to leave it.”

For treasure hunting divers, the anchor would be a great find..and indeed it was. In 2008, Anchor Ventures, LLC of Seattle decided that instead of searching the Channel, they would search off Whidbey Island’s northwestern shore. Their bet that the Chatham wasn’t with the Discovery at the time of the storm paid off. Anchor Ventures pulled up what they believe to be the long lost anchor. It was finally pulled up in 2014, and the team has been trying to prove its identity since. Skeptics say not so fast, this anchor is heavier than those of the late 1700’s.

Is the anchor still there? The search continues for the doubters of the 2008 find.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

MMGYS

Washington State Kurt Cobain is legend,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

John Tornow – The Wild Man of the Wynoochee, Washington

Satsop River, Washington

Coming from a respected family that homesteaded near the Satsop River, John Tornow was born on September 4, 1880. From the time he was just a small child, he preferred the unexplored wilderness near his home as his playground. As he grew, he spent more time with wild animals than he did with people.

When the boy was just ten years old his brother Ed killed his beloved dog and young John retaliated by killing Ed’s own dog. It was at this time that Tornow began to shun people altogether, vanishing into the woods for weeks at a time.

Hunting only for food, he learned to track as well as any Indian and his shooting skills quickly became legendary. He would return to his home only for brief visits with his parents, usually bearing gifts of game. By the time he reached his teen years, almost any animal would approach him unafraid, and his family had begun to think he was just a little bit crazy.

As his brothers entered the logging business, eventually owning their own company, Tornow occasionally worked as a logger, but more often continued to maintain his solitary ways in the wilderness. Living off the land, dressing in animal skins and shoes made of bark, John just wanted to be left alone with nature. Standing some 6”4” and weighing in at nearly 250 pounds, most people thought him a little strange, but harmless.

By the first decade of the 20th century, he was rarely venturing out of the woods but would occasionally watch the loggers as they were working. On one occasion he supposedly said to a logger, “I’ll kill anyone who comes after me. These are my woods.”

Convinced he was insane, his brothers captured him and committed him to a sanitarium in 1909. However, the facility, located deep in the heart of Oregon’s wilderness, was not able to contain the large man, as some 12 months later, he escaped into the forest.

Wynoochee Valley, Washington

Nothing was seen or heard of John for the next year until he began to occasionally visit his sister, her husband, and their twin sons, John and Will Bauer. He refused to have anything to do with his brothers, never having forgiven them for committing him to the sanitarium.

Spied occasionally with tangled hair, a long beard, and ragged clothes, his legend began to grow as people described him as a giant gorilla-like man seen running through the forest. Loggers would tell that he appeared to be a large hairy “beast” that would seemingly appear out of nowhere before once again vanishing into the forest.

In September 1911, Tornow shot and killed a cow grazing in a clearing by his sister’s small two-room cabin on the Olympic Peninsula. While he was dressing out his kill, a bullet whizzed over his head and dropping his knife, he lifted his rifle and fired three times in the direction from where the bullet had originated. When he went into the brush, he found his two 19-year-old twin nephews lying dead on the ground.

As to why John and Will Bauer shot at Tornow, it was suggested that the pair thought he was a bear feeding off of one of their herd. However, some historians believe that the boys intentionally made John Tornow their target. Though the truth will always remain a mystery, the mountain man, no doubt reasoned that someone was trying to capture or kill him when he returned fire. After seeing the dead bodies, Tornow quickly fled the scene disappearing into the deeply forested Wynoochee Valley. This incident would become the beginning of a legend that would grow large over the next several years and ultimately result in the death of the solitary mountain man.

William and John Bauer

When the Bauer boys did not return from home, their family contacted Chehalis County (Chehalis County would become Grays Harbor County in 1915) Deputy Sheriff John McKenzie. Soon, the deputy rounded up a group of more than 50 men to search for the brothers, who soon returned with the two dead bodies. Both had been shot in the head and stripped of their weapons.

McKenzie immediately announced that the shooting had to have been committed by John Tornow and a posse was rounded up to search for the wild man living in the forest. In no time, loggers and farmers making up the posse were roaming the Satsop area and the lower regions of the Wynoochee Valley, wary of the large man that they knew to have the intuition of an animal and the skills of an Indian.

The posse was skittish, terrified of the wild man, and when one group heard a sound in the brush, a shot rang out, killing a cow. Though the men were sure that Tornow was nearby each time they heard the slightest noise in the woods, they never spotted him.

The longer they searched and didn’t find the “ape-man” killer, the tales grew more and more exaggerated. Soon, the stories told of a cold-eyed giant constantly traversing the forest in search of prey, who soon earned such labels as “the Wild Man of the Wynoochee,” “the Cougar Man,” and “a Mad Daniel Boone.” With each telling, the story became larger and larger until the entire countryside was terrified. As the stories spread to the adjacent camps of Aberdeen, Montesano, Elma, and Hoquiam, no one felt safe with John Tornow on the prowl. Women and children were warned to stay indoors as the men oiled their hunting rifles and unleashed their dogs for protection.

As men continued to search into the winter they were forced into the lowlands due to deep snows. Tornow simply headed to higher terrain. Sometime later, the wild man broke into Jackson’s Country Grocery Store intending to help himself to a few provisions. Often he was known to burglarize cabins and stores in order to get what he needed to survive. However, on this occasion, he found more than just flour, salt, and matches, but also a strongbox filled with some $15,000. The grocery also served as the town’s bank.

In no time, Chehalis county offered a $1,000 reward for the return of the stolen money and despite their fears of the “wild man,” the number of men hunting Tornow dramatically increased. The blasts of gunfire could be heard echoing in the forest and on February 20, 1912, a gunshot-happy hunter killed a 17-year-old boy, mistaking him for Tornow.

The dense area where Tornow made his home is now part of the Olympic National Forest,

A few weeks later, a traveling prospector reported to Sheriff McKenzie that he had spotted Tornow at a camp in Oxbow. Together with Deputy Game Warden Albert V. Elmer, the pair headed out but found only a cold campfire at the point where Tornow had been spied. Sure that the money was buried somewhere close, the two began to look around. Though they were rewarded with two gold coins, they didn’t find the strongbox.

Sometime later both Sheriff McKenzie and Warden Elmer went missing and the reward was increased to $2,000. On March 16th, Deputy Sheriff A. L. Fitzgerald gathered up another posse to hunt for the “ape-man” in both Oxbow and Chehalis counties. Though they searched high and low for Tornow, what they found instead, were the bodies of Sheriff McKenzie and Albert Elmer. Both had been shot between the eyes and gutted with a knife.

Though the searches continued and Tornow was spied here and there, the mountain man continued to elude capture. A month later on April 16th, Deputy Giles Quimby, along with two other men by the names of Louis Blair and Charlie Lathrop, came upon a small shack made of bark. Sure that the crude cabin belonged to Tornow, Quimby wanted to head back for a posse, but the other two balked at having to share the bounty.

So, with guns ready, they approached the shack when a shot rang out, hitting Blair who fell into the nearby bushes. Lathrop returned fire but was immediately hit in the neck killing him instantly. Quimby, left alone with the marksman, desperately tried to negotiate with Tornow, telling him that all he wanted was the strongbox and promising to let the wanted man go free.

From his hiding place Tornow shouted, “It’s buried!”

Quimby continued to assert that he wanted nothing but the return of the money and would then leave John alone. Though Tornow was hesitant, not sure that Quimby would keep his word, the deputy assured him that he would let him go.

Deputy Giles Quimby

Finally, Tornow answered the deputy by stating, “It’s buried in Oxbow, by the boulder that look’s like a fish’s fin. Take it and leave me alone!”

Having retrieved the information from Tornow, Quimby didn’t keep his word, opening fire upon the foliage where John was hiding. Though no return shots were fired, Quimby wasn’t sure if he had hit the man or if Tornow might be just “playing dead.” Stealthily, Quimby scurried away through the woods.

When Quimby returned to Montesano, Sheriff Matthews gathered up another posse and the men began the trek back to the spot where Quimby had fired on Tornow. After cautiously approaching the trees, Tornow was found dead leaning against a tree. The men found $6.65 in silver coins on his body, identifying some of them as those taken from Jackson’s Grocery store.

Before Tornow’s body was even returned to Montesano, word had already reached the town that the “wild man” had been killed and curious gawkers began lining the street in order to get a peek at the legendary mountain man.

Deputy Sheriff Giles Quimby told newspaper reporters that John Tornow had “the most horrible face I ever saw. The shaggy beard and long hair, out of which gleamed two shining, murderous eyes, haunts me now. I could only see his face as he uncovered himself to fire a shot, and all the hatred that could fire the soul of a human being was evident.”

This further fueled the curiosity seekers’ desire to see the wildman’s face. In response, his brother Fred, who had traveled up from Portland, tried to prevent the body’s public display. However, when some 250 gawkers stormed the tiny morgue demanding to see the body, the overwhelmed coroner allowed them inside. Before it was said and done, the crowd required dozens of deputy sheriffs to prevent the nearly 700 citizens from tearing off bits of the dead man’s clothing and removing locks of his hair.

Fearing that those who were unable to view the body at the morgue would appear at the funeral, his service was held at the family’s old homestead. Immediately, postcards were printed that featured a photo of Tornow along with numerous newspaper articles with screaming headlines calling Tornow “The Great Outlaw of Western Washington.”

Of his brother’s death, Fred Tornow would, when questioned by the press, say: “I am glad John is dead. It was the best way now that it is over, and I would rather see him killed outright than linger in a prison cell.”

Customary in the days of the early 20th century, photos were taken of the dead. This photograph of John Tornow's corpse appeared on postcards the very day of his funeral.

Customary in the days of the early 20th century, photos were taken of the dead. This photograph of John Tornow’s corpse appeared on postcards the very day of his funeral.

The Oregonian newspaper noted that at the time of Tornow’s death he had $1,700 on deposit in a Montesano bank, owned real estate in Aberdeen, and was a part owner of a timber claim in Chehalis. Giles Quimby was proclaimed a hero for finally killing the feared “Wild Man of the Wynoochee,” so much so that he received offers to appear on stage to tell of his gruesome tale. Quimby politely turned down these offers.

When the furor of Tornow’s death had settled, Quimby went looking for the boulder that looked like a fish’s fin and was delighted when he found it. However, his happiness was short-lived, as search as he might, he never found the strongbox. Numerous other men followed in his footsteps, looking all over Oxbow, Washington, but the $15,000 treasure was never found.

The money is thought to be buried on the Wynoochee River where it turns into a large, horseshoe-shaped creek. However, a dam has since been built upstream, which may have caused a change in the river’s flow. Tornow said that he buried the cache near a fin-like rock. The hiding place is within the Olympic National Forest, which requires permission to hunt.

Tornow was buried in Matlock Cemetery in Grays Harbor, Washington, where his tombstone stands today.

Customary in the days of the early 20th century, photos were taken of the dead. This photograph of John Tornow’s corpse appeared on postcards the very day of his funeral.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

MMGYS*

Jimi Hendrix Legend from Washington state

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Victor Smith and a Tale of Three Lost Treasures

Port Townsend Customs House

In 1861, President Abraham Lincoln appointed a man named Victor Smith, a newspaper editor from Cincinnati, Ohio, as Collector of Customs for the District of Puget Sound, Washington. However, when Smith arrived, he immediately took a dislike to Port Townsend, thinking it no more than a city of “huts” populated by uncouth Westerners.

An ambitious man, Smith began to promote moving the Customs House from Port Townsend to Port Angeles. With the nation in the midst of the Civil War, he further supported his plan by advocating the idea that the British intended to join forces with the Confederates and the existing Port of Entry could be easily invaded from the British naval base on Vancouver Island in British Columbia.

In anticipation of the move, Smith, along with four other men, acquired land in Port Angeles and formed a Townsite Company to develop the new community. The townsfolk of Port Townsend soon learned of Smith’s plan, which of course, created feelings of hostility in the burgeoning community of Port Townsend.

When Smith’s letters to the Treasury Department failed to get immediate results, Smith traveled to Washington D.C. to promote his plan to fortify Port Angeles and relocate the Customs House there. Promoting Port Angeles’ superior location because it was nearer the ocean, he convinced Congress to move the Customs District of Puget Sound from Port Townsend to Port Angeles. It was made official in June 1862.

Port Townsend, Washington by E.S. Glover, 1878

However, all was not going exactly as Smith had planned. While he was celebrating his success on his return voyage to the west coast, the Acting Collector of Customs in Port Townsend, Lieutenant Merryman, was auditing the books of the Customs House. Finding the accounts short some $15,000, Merryman immediately reported the discrepancy to the Treasury Department by letter.

When Smith returned to Port Townsend on August 1, 1862, Lieutenant Merryman refused him access to the Customs House, accusing him of embezzlement and insisting that he would await official clearance from the Treasury Department before allowing Smith to return to his duties.

But Smith was not to be deterred. Returning to the ship on which he had arrived, he ordered the captain to train his three 12-pound cannons on the Customs House and the city’s commercial district. With the guns trained on the city, Merryman finally gave up the records and the ship sailed for Port Angeles.

Incensed, Port Townsend citizens soon traveled to Olympia to protest Smith’s actions to the governor. Though a federal grand jury indicted Smith with 13 counts of embezzlement and misuse of public funds, the Treasury Department quashed the indictment after their investigation.

In the meantime, Smith was constructing a large building in Port Angeles which served as both his family home and the Customs House. But, the Port Townsend citizens were not done fighting and began to build a case denouncing Smith and the transfer of the Port of Entry to Port Angeles.

After Smith completed the building in Port Angeles that served as both his home and the Customs House, a portion of it was rented to the government for its use. However, the building was to be short-lived as in December 1863, a landslide in the Olympic Mountains caused the dam to burst, sending a torrent of water through the town. Leveling most of the city and sweeping the Customs House into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, two customs employees were killed in the disaster. Smith was out of town and his family was spared.

It was this disaster that leads to the first treasure tale. Inside the Customs House was a strongbox that allegedly held $1,500 in bank notes and numerous $20 gold coins valued at $7,500 at the time. While some say this money was funds that Smith had stolen during his tenure as a Customs Agent, others contend it was money rightfully paid to him by the government for his home in Ohio. In any event, the strongbox was swept away in the flood and no trace of it has ever been found.

Finally, President Lincoln removed Smith as a Customs Collector in January 1864. However, his “friends” at the Treasury Department gave him a new role as a special agent.

In this new job, Smith was often tasked with transporting large sums of money. In 1865, he and his family had been on the east coast and while returning to San Francisco on the Gold Rule, Smith was tasked with transporting a large amount of payroll funds to San Francisco. However, on the ships passage from New York to San Juan, it wrecked on the Roncador Reef near the Isthmus of Panama. Though no loss of life was suffered, the ship floundered for 11 days as the 700 passengers survived on supplies salvaged from the vessel. When they were rescued by two gunboats, the passengers were taken to Panama. In the mass confusion following the wreck, the strongbox containing the money mysteriously disappeared. Smith remained on the reef endeavoring to salvage the chest containing the money. The tale continues that with the aid of a diver, the chest was recovered; however, the gold was missing. Though Smith accused the captain of the theft, many thought it was Smith himself who had absconded with the money.

In the meantime, Smith’s family had crossed the Panama Canal by railroad and returned to San Francisco on the sailing ship “America.” Two weeks later, Smith followed, reaching San Francisco and transferring to the Brother Jonathan on July 28, 1865, for the trip to Port Angeles. Did the payroll funds from the east coast wind up at the bottom of the ocean near the Roncador Reef or did it go with Smith when he finally made his way to San Francisco?

After transferring to the Brother Jonathan, Smith was again accompanying a large amount of money – some $200,000 to pay the troops at Fort Vancouver, Walla Walla, and other posts in the Northwest. The ship was also thought to have been carrying crates of $20 gold pieces for transfer to Haskins and Company as well as Wells Fargo. A government Indian Agent for the Northwestern Region may have also brought gold coins on board for annual treaty payments to the tribes.

As the Brother Jonathan passed through the Golden Gate and headed north, they faced a strong headwind and heavy seas, which continually worsened during its journey. The next day, the ship pulled into the harbor at Crescent City to offload cargo. On her way again, the storm was building and the ship headed westward to avoid the rocks of St. George’s Reef. As the storm continued to rage, Captain DeWolf decided to return to Crescent City, California to wait out the storm.

However, on July 30, 1865, the ship hit a rock and began to break up. Many of the passengers loaded into life boats were immediately thrown out as the smaller boats capsized. In the end, of the 244 people on board, 19 only people survived in a damaged boat that hobbled into the Crescent City harbor. For weeks, bodies washed ashore, but of the gold and money on board, it was never found. Victor Smith was one of the casualties.

In 1866, the Customs Port of entry was returned to Port Townsend, among great rejoicing by the citizens.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Mining Pyrite and Quartz Crystals

MMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Where Can I Find Gold In Washington State?

MMGYS

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

click on top part of videos for links

.jpg)

Join the InvestorsHub Community

Register for free to join our community of investors and share your ideas. You will also get access to streaming quotes, interactive charts, trades, portfolio, live options flow and more tools.